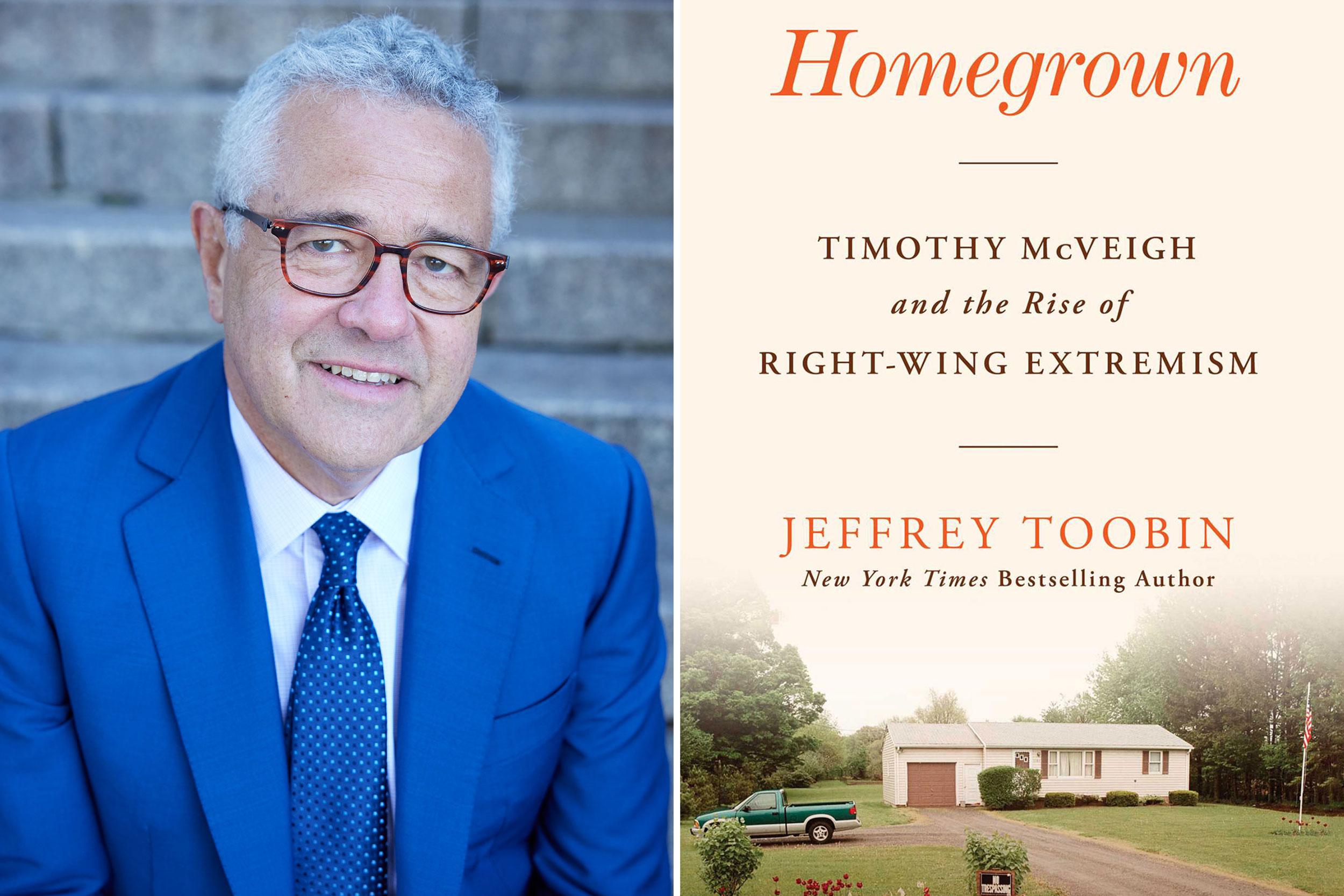

Photo by Shannon Greer

Who was responsible for Jan. 6 attack? Try Timothy McVeigh

Jeffrey Toobin examines how Oklahoma City bomber’s beliefs about guns, Founding Fathers, power of violence have been embraced by extreme right

Excerpted from “Homegrown: Timothy McVeigh and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism” by Jeffrey Toobin ’82, J.D. ’86.

The spirit of rebellion was in the air on January 6, 2021. Vice President Mike Pence was due to certify Joseph Biden’s victory in the 2020 presidential election in a ceremony at the Capitol. But supporters of President Donald Trump, and Trump himself, were mobilizing for a confrontation they hoped would change the outcome. The Proud Boys, a right-wing extremist group, had crafted a nine-page plan for storming the Capitol and other buildings in Washington; it was called “1776 Returns.” Two days earlier, Stewart Rhodes, leader of the Oath Keepers, another extremist outfit, said, “We’re walking down the same exact path as the Founding Fathers.” On the eve of congressional certification, Alex Jones, the InfoWars host and conspiracy theorist, held a boisterous rally a few blocks from the White House and said, “We declare 1776 against the New World Order. We need to understand we’re under attack, and we need to understand this is 21st-century warfare and get on a war footing.” He then went on an InfoWars broadcast to say, “This is the most important call to action on domestic soil since Paul Revere and his ride in 1776.” (The ride was actually in 1775.) On the morning of January 6, Lauren Boebert, the Republican congresswoman from Colorado, tweeted: “Today is 1776.”

By that time, crowds were already gathering at the Ellipse to hear Trump rally the troops. Rudy Giuliani, the president’s lawyer and warm-up act, told the crowd, “Let’s have trial by combat!” When it was his turn onstage, Trump sent the same message. “You’ll never take back our country with weakness. You have to show strength, and you have to be strong,” he told the throng. “We’re going to walk down Pennsylvania Avenue. I love Pennsylvania Avenue. And we’re going to the Capitol. And we fight. We fight like hell. And if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.” Thus roused, thousands of his supporters marched that way.

At the Capitol, the swarming crowd chanted, “1776! 1776!” Many flew the Gadsden flag, the yellow banner of the revolutionary era, which bears the words DON’T TREAD ON ME. When the Capitol rioters spoke of the Constitution, it was almost always of only one provision — the Second Amendment. They regarded the right to “bear arms” as a license for citizens to fight back against the government. As Rhodes, of the Oath Keepers, put it, the purpose of the Second Amendment was to “preserve the ability of the people, who are the militia, to provide for their own security” and “to preserve the military capacity of the American people to resist tyranny and violations of their rights by oath breakers within government.”

Later, many of the January 6 rioters explained their actions as analogous to those of the colonists during the American Revolution. “When we talk about 1776, we see that there was a lot of violence. We had to go against the government, and people died. And something good came out of that,” D. J. Rodriquez, one of those arrested inside the Capitol, told his FBI interviewer. “I, personally, felt that this is something that the Founding Fathers of the country understood was going to happen again one day and that we would be needed to do something righteous.” Defending the insurrection, Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene, who operates as the id of the modern Republican Party, said, “And if you think about what our Declaration of Independence says, it says to overthrow tyrants.”

* * *

Nineteen days after the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, Timothy McVeigh was summoned from his cell for his first meeting with his attorney, Stephen Jones. In that initial conversation, McVeigh was only too pleased to take credit for the attack on the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. From the start, Jones knew that the case of the Oklahoma City bombing was no whodunit.

So, in his first conversations with McVeigh, Jones wanted to explore a simple question: Why? Why had this 27-year-old man, who appeared ordinary in so many ways, committed this horrific act?

As he entered the prison conference room, McVeigh had his hands manacled behind him. In a small concession, he was allowed to be cuffed in front when he sat at the metal table bolted to the floor. “Call me Tim,” McVeigh told Jones. They made small talk about the inmate’s mail. He had already received a marriage proposal and $10 in cash.

When Jones moved on to the bombing, McVeigh continued in the same relaxed, almost serene way. He talked about mass murder just as he did about his beloved Buffalo Bills. For McVeigh, the destruction of the Murrah building, and of the lives of those inside it, was more than just permissible. It was mandatory, his duty as a patriotic American. He had no regrets, no second thoughts.

How could McVeigh see murder as justified, much less required?

Read the Declaration of Independence, he instructed his lawyer — and not just the famous part. To McVeigh, the more important section of the Declaration came later, and he recited it from memory: “Whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it. … When a long train of abuses and usurpations … evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government.” McVeigh took the same message from Patrick Henry’s famous speech from 1775, the one which concluded “Give me liberty or give me death.” He recited what else Henry had said: “If we wish to be free — if we mean to preserve inviolate those inestimable privileges for which we have been so long contending … we must fight! I repeat it, sir, we must fight!”

At the Murrah building, McVeigh fought.

His actions, he explained, were a direct response to the “abuses and usurpations” of the federal government, especially those at Ruby Ridge and Waco. In the months that followed, McVeigh would return obsessively to these two events, just as he had fixated on them in the period leading up to the bombing.

The Ruby Ridge saga began in August 1992, in rural Idaho, when U.S. marshals attempted to serve an arrest warrant for weapons charges on a right-wing activist named Randy Weaver. When Weaver refused to surrender, the marshals and FBI began a siege on his property. In one skirmish, a deputy marshal and Weaver’s 14-year- old son (as well as the family dog) were killed. A few days later, an FBI sniper killed Weaver’s wife as she stood in a doorway holding their baby daughter. After an 11-day standoff, Randy Weaver surrendered.

Six months later, in February 1993, the Waco siege in Texas followed a similar pattern, with even more disastrous results. Agents from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms attempted to serve arrest and search warrants for weapons charges at a compound run by a religious sect called the Branch Davidians. During that original operation, four federal agents and five Branch Davidians were killed in a firefight. The FBI took over the scene and conducted a siege of the buildings, which were controlled by David Koresh, the Davidians’ leader. After 51 days, on April 19, the FBI launched a tear gas assault on the compound, which caught fire. Seventy-six Branch Davidians, including Koresh, died in the conflagration.

McVeigh chose to bomb the Murrah building on April 19 because it was both the second anniversary of the Waco raid and also the date of the “shot heard round the world” in 1775, the beginning of the American rebellion against the British. In his own mind, McVeigh was the heir to the heroes of the Revolution. As McVeigh told his lawyer, “the government laid down the ground rules for warfare” in Ruby Ridge and Waco.

But it wasn’t just Ruby Ridge and Waco. There was President Bill Clinton’s support of a bill banning assault weapons. McVeigh received a BB gun from his grandfather when he was nine years old, and he remained obsessed with firearms for the rest of his life. He loved to shoot, and he was a skilled marksman in both civilian and military life. The issue of guns represented the core of his political worldview as well, a lesson which he also said came from the Founding Fathers. While McVeigh had not read many books about American history, he had steeped himself in right-wing magazines. McVeigh endorsed the view of the Framers’ intentions that was published in Soldier of Fortune, and The Spotlight, published by Liberty Lobby. He told Jones that his hero Patrick Henry called guns the “teeth of liberty,” and McVeigh loathed any attempt to regulate their possession.

“How are patriots supposed to defend themselves when their right to bear arms is infringed?” he asked Jones. “The best defense is a good offense. They’re coming for the gun owners next. Enough is enough.”

There were, then, three powerful ideological motivations for McVeigh’s decision to bomb the Murrah building: the obsession with gun rights; the perceived approval of the Founding Fathers; and the belief in the value and power of violence. In the decades since his death, the rise in right-wing extremism, the January 6 insurrection, and much in the contemporary conservative movement, show how McVeigh’s values, views, and tactics have endured and even flourished. That makes the story of Timothy McVeigh and the Oklahoma City bombing not just a glimpse of the past but also a warning about the future.

Copyright © 2023 by Jeffrey Toobin. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.