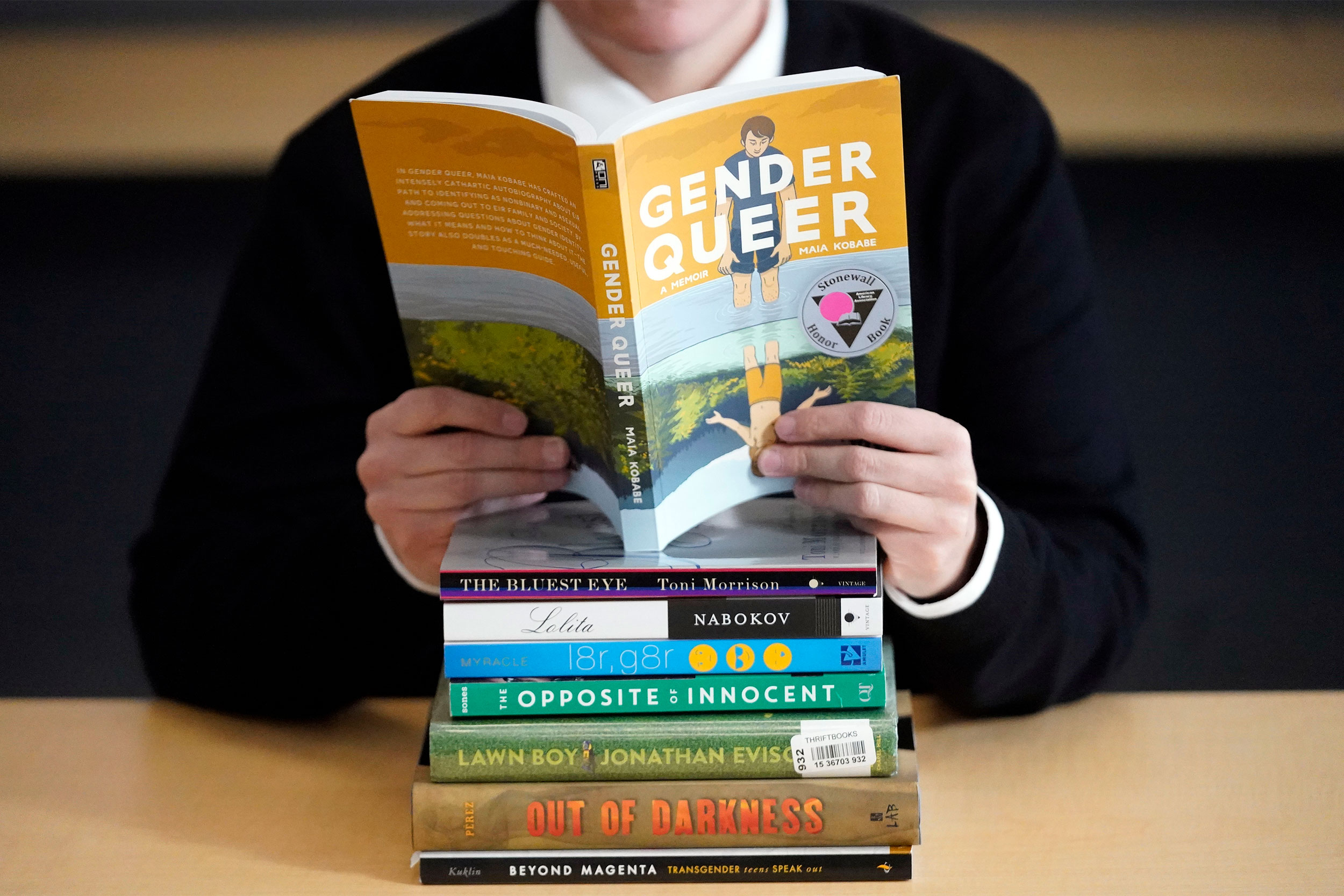

Rick Bowmer/AP file photo

Who’s getting hurt most by soaring LGBTQ book bans? Librarians say kids.

Experts note challenges across nation being pushed by vocal minority, reflect backlash to recent political, social advances

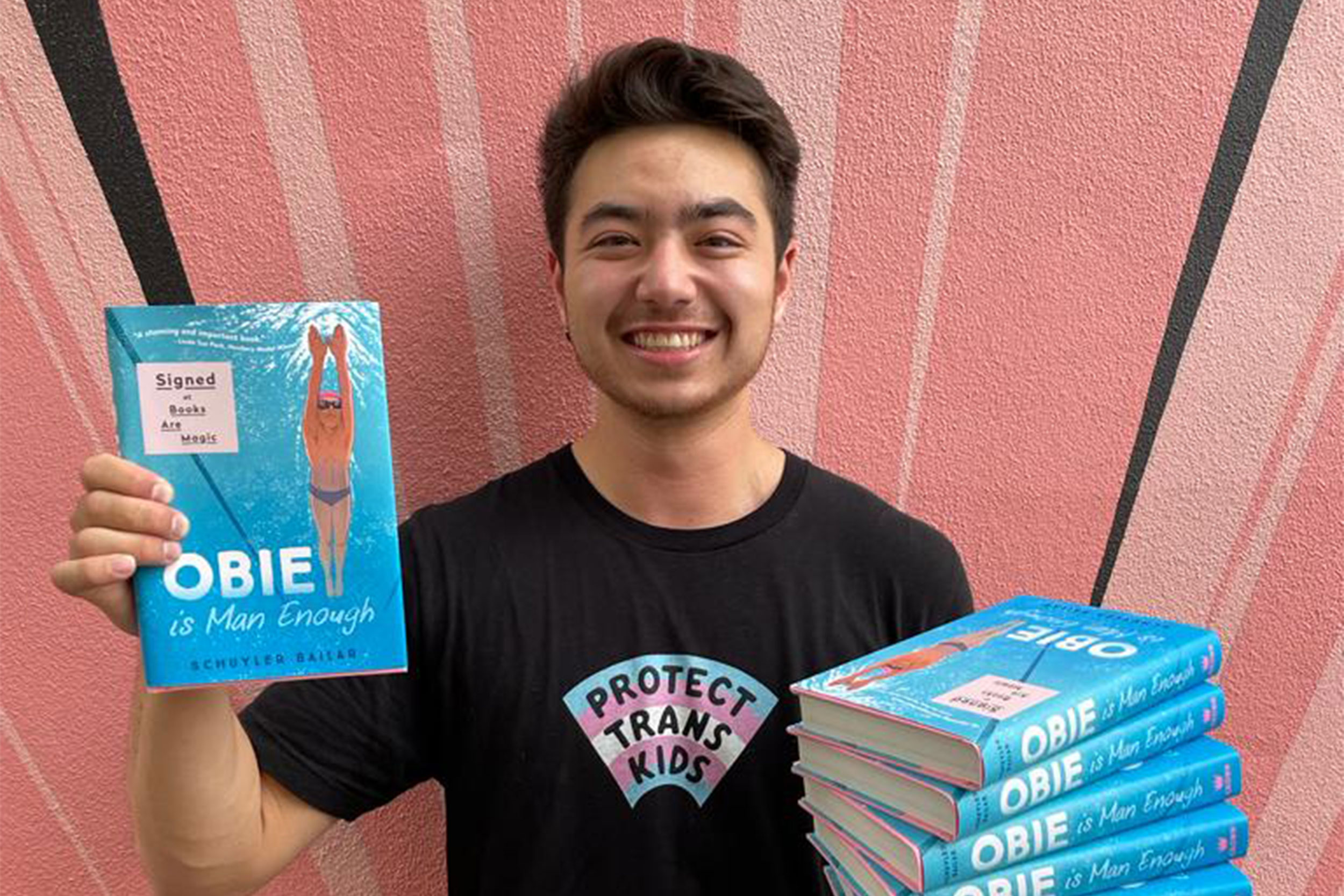

When Schuyler Bailar was a child, he didn’t see many books that reflected his identity. Not his mixed-race identity, and especially not his developing gender identity. It’s one of the reasons the first openly transgender NCAA Division I swimmer decided to write “Obie is Man Enough,” a 2021 novel about a transgender middle school swimmer.

“I wanted to write about kids like me because kids like me exist,” said Bailar, a 2019 graduate of the College. “Writing this story would be a way to help remind other kids like me that they’re not alone.”

But getting books about LGBTQ issues into the hands of young readers is becoming more difficult with the recent rise of book bans across the nation. PEN America recorded more school bans during the fall 2022 semester than in the prior two. The American Library Association documented 1,269 attempts to ban or restrict books in libraries last year. This is the highest number since the group began tracking the issue two decades ago and nearly doubles the previous record set in 2021. Nearly half — 45.5 percent — of 2,571 unique titles challenged were written by or about LGBTQ people.

“My book isn’t allowed in a lot of states right now that ban talking about gender identity,” Bailar said. One teacher in Charles City, Iowa, resigned after being placed on administrative leave for teaching a short story by Bailar about his first time swimming for Harvard on the men’s team.

“These book bans absolutely affect authors, but I think they affect the children more,” he said. “Our stories are not getting out to the kids who need to be reading them.”

Michael Bronski, Professor of the Practice in Media and Activism in Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality, said the challenges reflect political and social tensions due to the rapid change in acceptance of LGBTQ people.

“We’ve had enormous progress [for LGBTQ rights],” Bronski said. “These book bans — along with the bans on drag shows, along with the attacks on abortion, along with the attacks on trans youth — are really a last-ditch effort, almost magical thinking [from conservatives], to stop this push.”

The number of targeted titles may be increasing, but it appears to be less a matter of growing disapproval of parents and others and more about a shift in tactics by groups. Historically, requests for censorship or restriction focused on single books. In 2022, the majority involved multiple titles, with 40 percent of cases calling for bans of 100 books or more.

Lesliediana Jones, associate director for public services at Harvard Law School Library, refers to this new practice as “copycat challenging,” where one group compiles a list of books then shares that list — sometimes through social media — with others to mount challenges at their local schools and libraries. This is a primary driver in the rapid increase in calls for censorship.

“You didn’t have the mechanisms and the media methods you have now,” Jones said. “[Book challenging has] escalated because these groups have become a lot more well-funded and a lot more organized.”

The primary reason cited in many LGBTQ book challenges involves sexual content; however, many are also explicit in their intent to prevent children from reading about LGBTQ people and their lives, according to an investigation by The Washington Post. The Post also found that while book challenges have become many, the challengers themselves are few, with only 11 people responsible for 60 percent of filings nationwide.

“I think it is a small and very loud minority that is weaponizing — I sort of hate the word weaponizing — but they are weaponizing and passing these laws” on book restrictions, Bronski said, referring to legislation in states like Florida, Utah, and Missouri. He doubts any of the legislation will withstand scrutiny by the courts, but that’s not to say that “grave damage” isn’t being done.

“The main intention of all of these laws is to actually — an impossible task — eradicate the visible presence of queer people,” Bronski said. “If we think of the world as the legal sphere and the social sphere, the social sphere has actually evolved pretty quickly, and some people … are uncomfortable with that, and they’re using legal tactics to stop that.”

But Bronski said these efforts can foster uncertainty and doubt in society and affect how the LGBTQ community is perceived. In a recent Gallup poll, acceptance for LGBTQ people dropped 7 percent across both Democrats and Republicans, with only 41 percent of Republicans supporting LGBTQ people, down from 56 percent a year ago.

Jones, who is also the chair of the Intellectual Freedom Committee for the ALA, said that as a librarian, their job is to provide content that can reflect the entire community. Parents are within their right to help decide what their child can or cannot read, but removing a book from a library makes that decision for all patrons. In recent years, librarians who have refused to remove certain books from their shelves have come under attack by parents who say they don’t want their children exposed to content they view as sexually inappropriate. Jones said that’s simply not the reality.

“You’re not putting ‘Gender Queer’ next to ‘Pat the Bunny,’” Jones said, referring to the top banned book in 2022. “I trust that the librarians at whatever library have looked at the books and put them in the appropriate section.”

Alex Hodges, director of the Gutman Library at Harvard Graduate School of Education, said it’s important for parents who have concerns about what their children are reading to communicate with their librarians, but it must be in a way that is respectful and appropriate. Professional librarians use criteria to vet books, and parents are free to challenge the process. However it should be part of a dialogue, one that allows both parties to voice specific, concrete concerns.

Illinois recently became the first state to ban book bans; Bronski and Jones agree that it’s a step in the right direction, but not enough.

“I think that banning book bans is great. I’m all for it, but it doesn’t address the real problem,” Bronski said. “You have to change the hearts and minds of Americans.”

For Bailar, whose latest book “He/She/They: How We Talk about Gender and Why It Matters” will be available this fall, hopes society will move to a wider acceptance of LGBTQ experiences. He says when he makes visits to education settings some people he meets are “stunned” to discover they can connect with him, that he’s a real person deserving of “universal human empathy.” He wants this same acceptance extended to trans youth.

“We know when kids aren’t allowed to be who they are until they’re adults — or if they have to hide their identity — it’s harmful to them,” he said. “When we affirm children’s identities, we can actually save their lives.”