Voters in Detroit casting ballots in the 2022 midterm election. Danielle Allen points out that voting turnout rates in the U.S. are lower than other developed democracies.

Jim West/Alamy Live News via AP

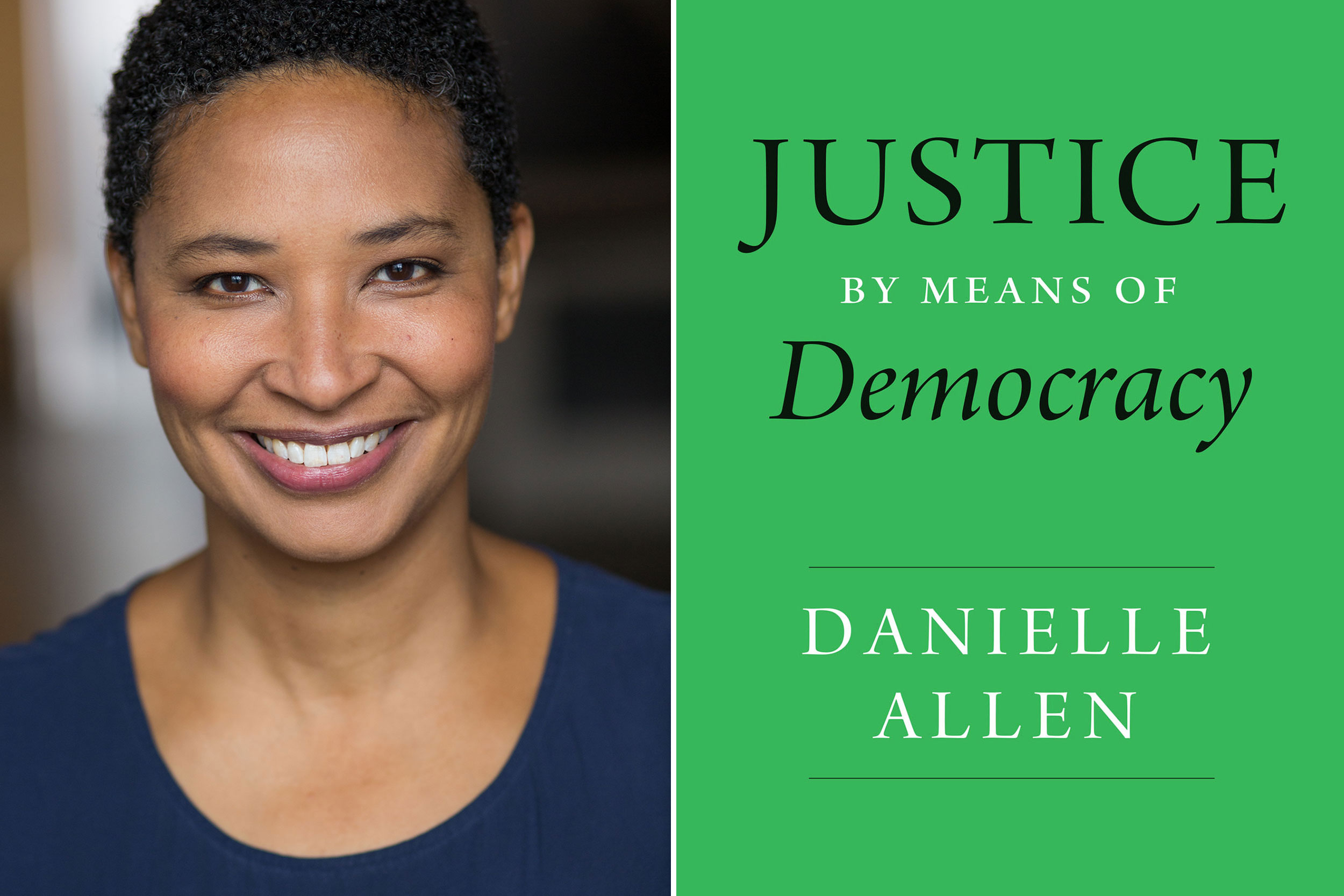

Danielle Allen thinks our democracy needs renovation

Her new book lays out vision for power-sharing liberalism that will lead to greater inclusion, responsiveness, participation — and better lives for all

In Danielle Allen’s vision for a just society, every citizen would experience empowerment — both in their private lives and in our shared governing. Achieving this, according to Allen, requires a world where people have a work-life-civic balance and certain foundational needs assured: straightforward and affordable healthcare, low housing and energy costs, and good jobs that integrate people into the productivity of a dynamic, inclusive economy.

None of it can be achieved without greater inclusion, responsiveness, and participation in democracy said Allen, James Bryant Conant University Professor and director of the Edmond and Lily Safra Center for Ethics, who explores this framework of “power-sharing liberalism” in her new book, “Justice by Means of Democracy.”

“It’s not a never-been-seen-before concept. It’s just that, so far, we’ve only partially achieved power-sharing,” said Allen, who envisions greater representation in government positions as well as employers allowing workers time to participate in civic life. “That is what it means to see diversification of who serves in office, to see diversification of leadership positions all over society. It’s in development all over this country, but we can be better at it.”

Allen sat down with the Gazette to discuss her book, and the course on the same topic that she taught this semester. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q&A

Danielle Allen

GAZETTE: In your book, you argue that the surest path to creating a just society where individuals can flourish is through democracy, with citizens being active participants and sharing power with one another. What inspired you to write about this topic?

ALLEN: I’m from people who have loved and fought for democracy, so as a matter of family inheritance I have a fundamental commitment to democracy as a human good, as a source of empowerment for individuals, families, and communities.

On my dad’s side, my granddad helped found one of the first NAACP chapters in northern Florida in the ’40s, which was very dangerous work. On my mom’s side, my great-grandparents fought for women’s right to vote, and my great-grandmother was president of the League of Women Voters in Michigan in the ’30s. I was fortunate to grow up in a network of people — aunts, uncles, and cousins — all of whom were very politically and civically engaged, and I kind of took democracy for granted.

That was true until I watched my own generation coming up in the world. In my parents’ generation everybody moved up, but my generation has experienced what I call a “great pulling apart.” Here I sit as a tenured professor at Harvard, which I consider to be literally the most privileged role in the world, but at the same time I have cousins who aren’t with us anymore due to substance-use disorder and homicide. That story of the great pulling apart in my family has coincided with a great pulling apart in the country’s history: income inequality, wealth inequality, mass incarceration, and polarization.

It was really when I lost my youngest cousin, Michael — which I’ve written about in an earlier book, “Cuz” — that I’ve been trying to answer these questions about: “What would it take for democracy to establish that foundation for flourishing, and enable us to pull together again?” I kept seeking answers, and over time it led to this argument, which puts democracy at the center of the theory of justice.

GAZETTE: Could you explain “power-sharing liberalism,” and what makes it different?

ALLEN: Liberalism consists of two things: protection of rights and the question of how you organize parts of government to secure those rights. The basic idea is that if you’re going to actually achieve the vision of full protection of rights, that requires actual full sharing of power and responsibility as well. You can’t reserve power to a few — whether it’s people with property or white men or technocrats. You can’t do it if your goal is, actually, securing rights for all.

The history of philosophy has typically divided rights into two categories: negative liberties or freedoms from interference by the government, and positive liberties or freedoms to participate. For more than a century, liberal political philosophy has prioritized the negative liberties over the positive liberties, so negative liberties have been considered “non-sacrificeable,” but the positive liberties (the goal of participation) have been considered “sacrificeable.”

So the idea has been that you could have a just society if people don’t really get to participate, as long as you have benevolent public servants who are protecting negative liberties. But I’m saying you won’t get the actual protection people need unless people have fully protected positive liberties as well.

GAZETTE: What does ideal power-sharing look like, and what trends are we seeing in the U.S. currently?

ALLEN: Decision rights in political institutions, so political participation, but also in organizations and all the different structures of civil society. The decision rights in public institutions are operationalized through voting, but also through jury duty and through appointed service, through writing letters to your representatives, through running for office.

All over this country our voting turnout rates are lower than in other developed democracies. And in too many states across the country registration rates for Hispanic, Asian American, and African American citizens are below 50 percent.

Also all over the country you have local offices, both elected and appointed, that aren’t filled because people aren’t even aware of them or aren’t running for them. At this point, we have news deserts all over the country that make it really hard for people to see what their public officials are actually doing, so they can’t hold them to account. We have very few contested elections, generally speaking.

So there are a lot of things that are unhealthy about our current structures of participation. Power-sharing is about bringing health in all those dimensions, and my argument is that if we could get this right, we would also see improvements in our ability to address shared problems.

GAZETTE: You’ve also been teaching a course this semester with the same title as your book: “Justice by Means of Democracy.” What has it been like to explore this topic with students?

ALLEN: It was a real experiment. I set the course up to try to help the students see that there is a new paradigm emerging for thinking about political economy. We started off by looking at earlier thinkers: Keynes and Hayek and Friedman and Nozick and Rawls; and then at a more recent generation of work: Amartya Sen, Elizabeth Anderson, Philip Pettit, and my book to help them see what changes for theories of society and the economy if you put this question of the distribution of power front and center in your analysis.

Then we spent time on public policy, looking at the kinds of policies that seem to matter more once you do this — housing policy, for example, and jobs policies. It was a fun class, because it was a blend of Kennedy School students and College undergraduates, and I think everybody appreciated that cross-School interaction. It was a highly engaged group of students who were in the class, and I think that the combination of political philosophy and public policy gave them a lot to chew on.