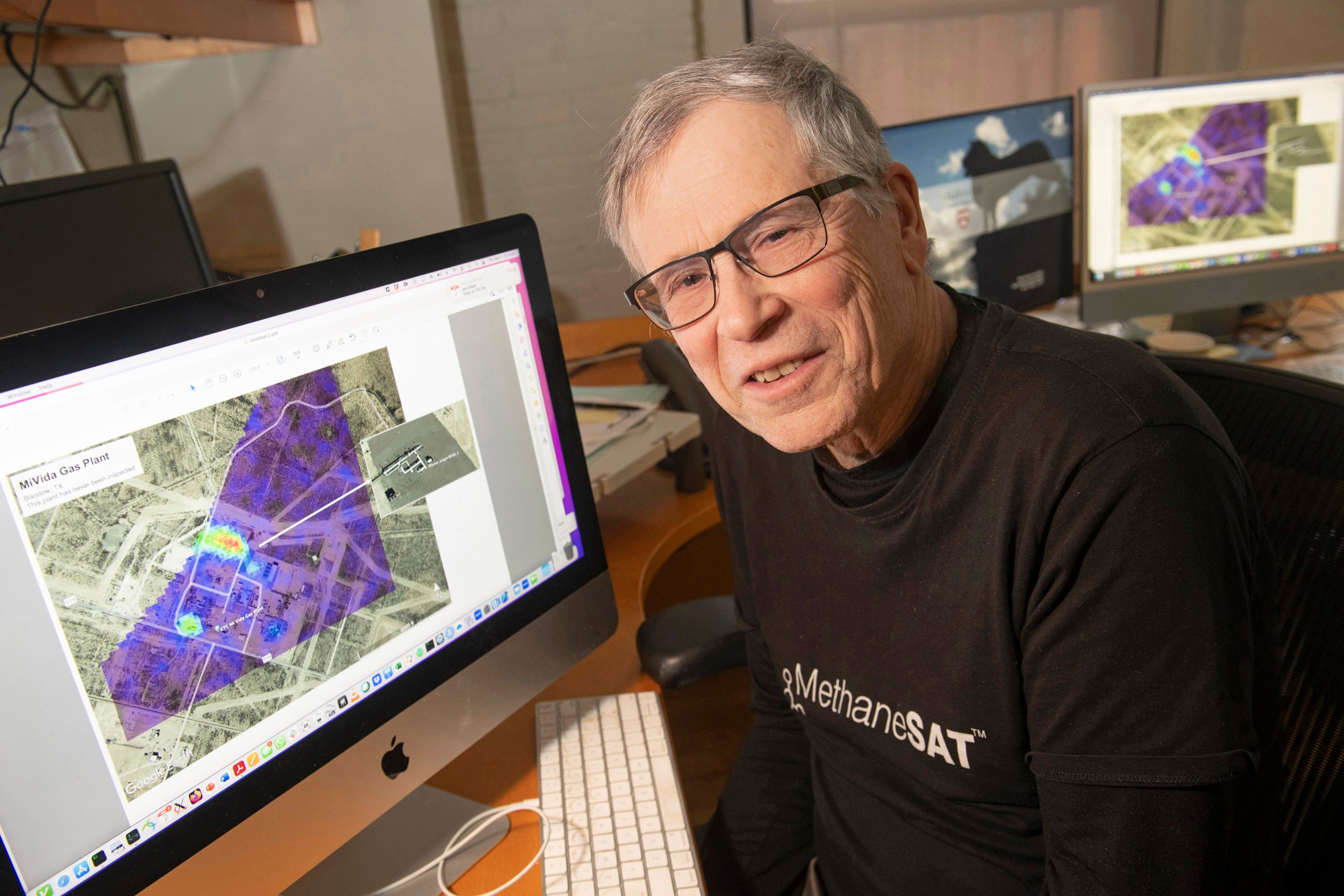

Harvard Professor Steven Wofsy is the principal investigator for the satellite project MethaneSAT.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Buying crucial time in climate change fight

MethaneSAT satellite will spot global sources of methane emissions, which in many cases can be halted with relatively simple fixes

For Steven Wofsy, the satellite is worth sticking around for.

Wofsy, an atmospheric scientist who spent decades investigating climate change, could be enjoying retired life at age 76, but he still has an active lab. Admittedly most projects there are winding down, with one exception: MethaneSAT, which could prove to be something of a game changer.

“The reason I’m not retired is that this is obviously way too important — and way too much fun,” said Wofsy, Harvard’s Abbott Lawrence Rotch Professor of Atmospheric and Environmental Science. “I’m not taking students in other areas, even though there are some things still going on. This is the focus, and it’s extremely challenging, but in a good way.”

More precise than other methane-sensing satellites that came before, MethaneSAT will allow scientists to track emissions to their sources and provide key data for reduction efforts. It’s important because it could buy the world critical time in the climate change battle. And, most hopefully, it appears particularly do-able in part because saving wasted methane provides a financial incentive for timely corporate cooperation in halting leaks.

With stronger storms, hotter heat waves, longer droughts, and other climate-related impacts already growing apparent, there’s an appreciation that what’s important is not just how much the world warms, but also how fast.

Steven Hamburg, EDF chief scientist

MethaneSAT is scheduled to launch early next year, and Wofsy is its principal investigator. The project is the result of a unique collaboration led by the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund and involves academic scientists, environmental activists, the private space industry, and philanthropic pockets deep enough to fund the design, construction, and launch of a satellite, which is traditionally the reserve of government and big business.

Wofsy and EDF chief scientist Steven Hamburg said the project was born partly out of frustration with years of government inaction on climate but also from a growing realization that curbing methane emissions can have important short-term effects on climate change. In fact, it has the potential to provide a decades-long bridge, slowing the near-term rate of warming and reducing the damage as the world transitions to the low-carbon energy sources that are a longer-term solution.

And perhaps the most important part: It appears actually do-able as it includes an incentive for timely corporate cooperation.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas — 84 times as powerful as carbon dioxide on a 20-year time scale — but has been in CO2’s shadow for two reasons. Carbon dioxide is emitted in much greater quantities and hangs around until removed by natural processes that can take centuries to millennia. That means the effects of the gas emitted today pile on top of those released over the last century, and the emissions of decades to come will only make the pile higher. Without steps to remove it, CO2’s cumulative effect will drive warming upward inexorably and, on a human time frame, irreversibly.

While methane drives just about 30 percent of the warming occurring today, what’s gotten everyone’s attention is its lifetime in the atmosphere: decades rather than centuries. Ironically, that brief lifespan is part of the reason why it has been overlooked. The year 2100 emerged early on as a climate-change milepost, a common marker by which to gauge progress toward solving the problem. But when impacts are considered over a century, short-lived methane and its impacts come and go while effects from the buildup of carbon dioxide grow larger and larger.

“Methane is a short-lived climate pollutant,” Hamburg said. “If you look at a pulse of emissions of something that doesn’t last very long, at its impacts over 100 years, you’re going to have a lower number. But if you ask what’s its impact over 20 years, you’re going to have a much higher number.”

With stronger storms, hotter heat waves, longer droughts, and other climate-related impacts already growing apparent, Hamburg said there’s a growing appreciation that what’s important is not just how much the world warms, but also how fast. An abrupt heating over 20 or 30 years will have impacts very different from those of a long slow warmup over 70 or 80, even if they ultimately reach the same temperature. The rapid increase allows little time for either nature or human societies to adapt. And methane, with its potent warming power and short lifetime, has the potential to act as a toggle between the two futures, Hamburg said.

“If we don’t do anything for 50 years and then radically reduce our methane, the amount of warming in 2100 won’t be different, but the rate of warming will be much higher if you delay, which will have big impacts — and even feedbacks — on the climate,” Hamburg said.

A landmark study

Wofsy has been keeping an eye on methane for decades. He has used everything from airplanes to balloons to a tower among Harvard Forest trees to better understand how greenhouse gases are changing the atmosphere. He has driven methane-sensing equipment around Boston searching for leaks in the area’s aging natural gas infrastructure, mounted instruments on rooftops and flown them from balloons to measure gases in the atmosphere.

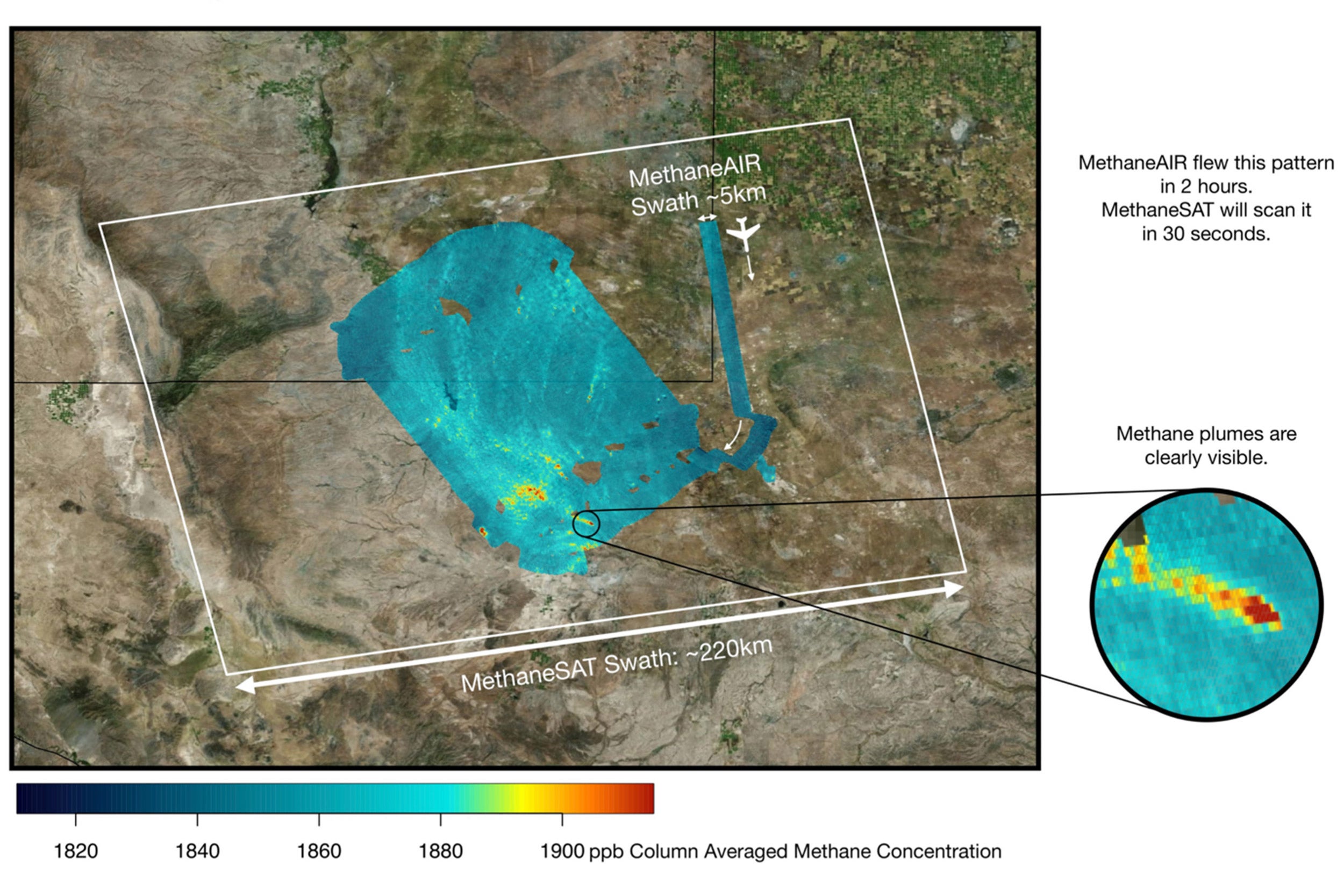

More precise than other methane-sensing satellites, MethaneSAT will allow scientists to track emissions to their sources and provide key data for reduction efforts. It is scheduled to launch early next year.

Courtesy of Steven Wofsy

Wofsy also participated in a nationwide study supported by EDF that had researchers across the country measuring methane concentrations near oil and gas facilities. The work, published in the journal Science in 2018, showed that when it came to methane, federal regulators didn’t really know what they were talking about. The amount of emissions found in the study was about 60 percent higher than EPA estimates. That’s enough that the warming caused by the excess methane, over 20 years, is roughly equal to that produced by burning natural gas for heating and cooking each year.

Wofsy became involved in MethaneSAT in 2015, when he got a call from a friend at EDF. The nonprofit wanted to expand its exploration of methane emissions to cover the globe and was considering using a satellite. It wanted Wofsy’s thoughts on the best way to do that and a cost estimate. Wofsy reached out to Kelly Chance, a senior physicist at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, and together they produced a report that put the price tag at tens of millions of dollars.

“We brought that back to EDF, and we assumed that that was the end of it,” Wofsy said. “But they went ahead and raised enough in private philanthropy to fund this thing.”

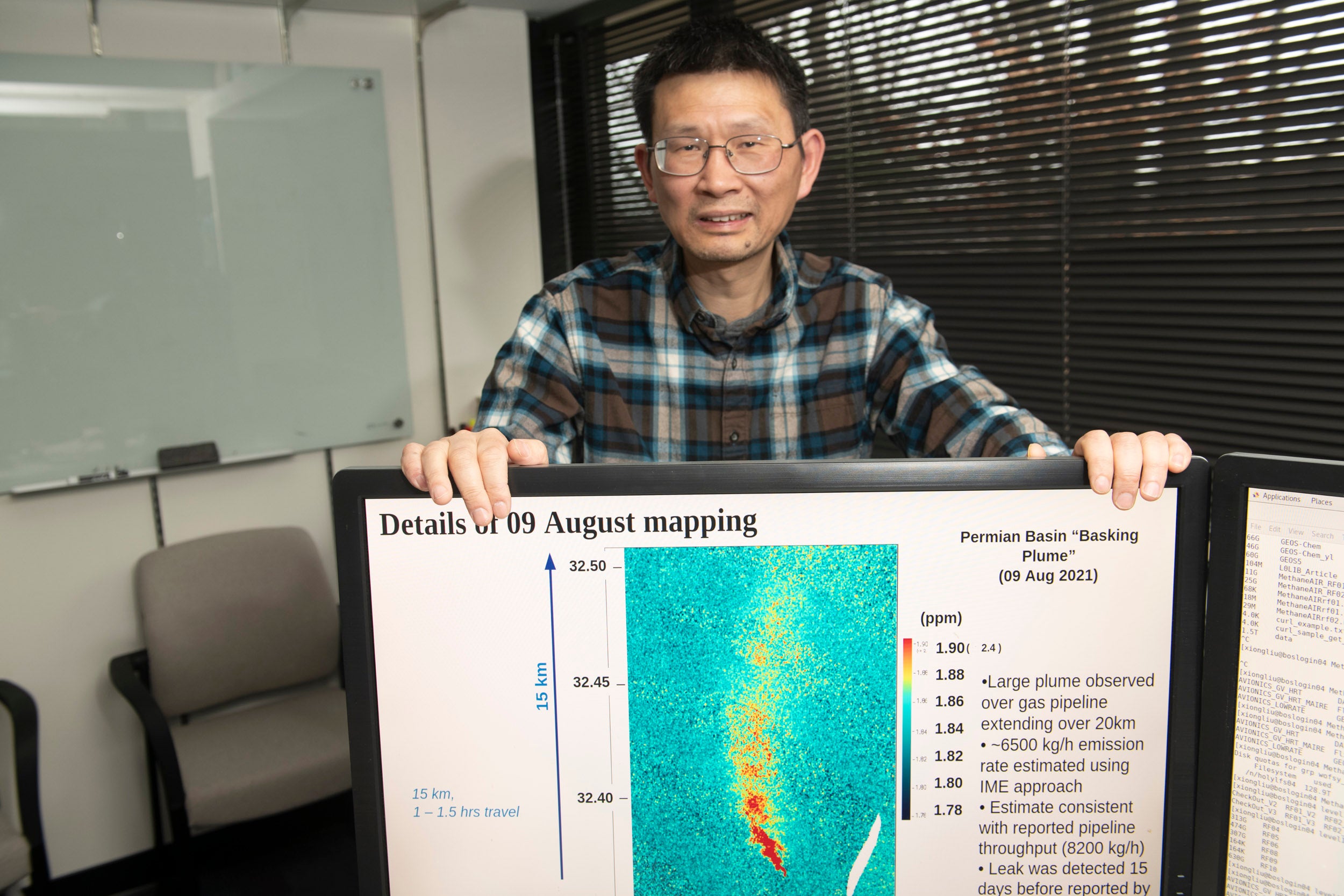

Wofsy signed on to oversee the mission’s science aspects. He brought with him Chance and other scientists from the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, the Smithsonian arm of the CfA’s Harvard & Smithsonian partnership. Among them was Xiong Liu, a CfA research scientist who became the SAO’s MethaneSAT lead. Liu and those working with him are seeking ways to determine methane abundances from the data, a crucial initial step before sources can be identified.

MethaneSAT’s main scientific instrument is a spectrometer, which breaks white light into a spectrum that bears the telltale fingerprints of molecules in the air through which the light passes. Harvard and SAO scientists provided specifications for the instrument, which was built by contractor Ball Aerospace. The instrument is currently being installed in the spacecraft that will carry it to orbit, Liu said. The satellite’s launch is planned for January 2024 from Cape Canaveral aboard a Falcon 9 rocket from SpaceX, whose founder and chief executive is billionaire Elon Musk.

The power of information

The MethaneSAT project has an ambitious policy goal: reduce global methane emissions from oil and gas facilities by 45 percent by 2025 and 70 percent by 2030. If achieved, it would have a similar impact on the climate over 20 years as closing one-third of the world’s coal plants, EDF said.

“What’s exciting about the MethaneSAT mission is it’s not simply collecting data, we’re putting data into action,” Liu said. “I think that’s the fastest way to slow down global warming. It’s exciting to be part of this project.”

While several satellites, both in orbit and in planning, are designed to detect methane, Wofsy said MethaneSAT will do so at a higher resolution than any other. It will allow researchers to determine methane concentrations, trace them to their sources, and track changes over time.

EDF plans to make the data publicly available — in near real time — to researchers, lobbyists, regulators, and others. In fact, Harvard’s Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability recently awarded a grant to a multidisciplinary project, headed by the Harvard Kennedy School’s Robert Stavins, that involves 17 faculty members from six Harvard Schools and seeks to leverage publicly available data on methane — including from MethaneSAT — to affect policies and cut emissions.

“We used to think about climate change as something for the distant future — the year 2100 or 2050. But now, as a result of events that have been taking place with the climate, whether it’s floods in Pakistan or fires in California, people have begun to give attention to climate change now,” said Stavins, the A.J. Meyer Professor of Energy and Economic Development, director of the Harvard Environmental Economics Program, and founder of the Harvard Project on Climate Agreements. “And when you do that, the relative importance of methane increases tremendously.”

The satellite will cover about 80 percent of oil and gas companies’ global production, and Hamburg expects the data it gathers to drive action. Some companies, he said, will recognize that the public nature of the data makes them hard to ignore and will begin to focus on emissions. Others will need an additional nudge, whether by the public, stockholders, or regulators. Still others may need their hand forced.

Helping the cause, Hamburg said, is that momentum toward plugging methane leaks and reducing emissions has been growing. The 2021 climate summit in Glasgow saw adoption of a global pledge to reduce methane emissions 30 percent by 2030, with 150 nations signing on as of November. Last year, the U.S. approved its most sweeping climate change action to date in the Inflation Reduction Act, which includes provisions for a Methane Emissions Reduction Program.

Hamburg and Wofsy said they’re optimistic that corporations will respond relatively quickly because the fixes aren’t technically difficult, involving things such as tightening pipelines and improving wasteful processes. In addition, the methane saved can be sold as natural gas, so any remediation will at least partly pay for itself.

While oil and gas installations are MethaneSAT’s initial focus, reducing those emissions alone won’t solve the problem. They are something of a low-hanging fruit, Hamburg said. Beyond that the problem becomes more complex. That’s because methane is produced in many different ways — both natural and anthropogenic — and emissions stem not just from fossil-fuel production, but also from cities, landfills, and livestock feedlots, each of which will demand a different approach to reduction.

Back in the lab

In Wofsy’s lab and at the Center for Astrophysics, scientists, doctoral students, and postdoctoral fellows signed on due to interest in MethaneSAT’s scientific and technological challenges, but they also say they believe in the mission.

“What we’re trying to do is very attractive,” said Jonathan Franklin, a senior project scientist in Wofsy’s lab who has been with MethaneSAT since its 2015 start. “This is, obviously, the key issue of our time, and this is a way that we can make meaningful change. You need data to have success.”

MethaneSAT’s instrument works by gathering sunlight that bounces off the Earth and reflects back to the satellite’s sensors. As the light moves through the atmosphere, different molecules absorb different wavelengths. By examining the light’s spectrum, scientists can tell how much methane is present. Much of the work at Harvard and the CfA involves devising and testing an algorithm that takes that raw data, accounts for variables that might affect the readings, comes up with a value for the amount of methane present, and then uses that value to determine the methane’s source location and emission rate.

Jonas Wilzewski, a postdoctoral fellow in the Wofsy lab, said the work involves adjusting for things like different reflectivity of the ground in different places, the presence of clouds, or of aerosols in the atmosphere that might scatter the light, and dealing with local meteorological conditions.

“There are many things going on in the atmosphere, and our job is to figure out what was the actual concentration of methane in the entire column of air below the satellite,” Wilzewski said. “This algorithm starts from the signal of photons that get collected, and then goes through how much methane was in the air. Then it goes to where we see an enhancement and then calculates how much methane per time was emitted from that location, so you can say, ‘Oh, look there’s a pipeline that has a defect.’”

Wofsy said interest in MethaneSAT endures even when he tells applicants that it is not a typical scientific endeavor and likely will not result in many scientific publications. Ju Chulakadabba, a Ph.D. student, is working on methods to determine point sources of emissions from the data, and said she was drawn to it for the chance to make a difference.

Last fall, Chulakadabba flew aboard a Gulfstream V research plane from the National Science Foundation equipped with instruments similar to those that will be aboard MethaneSAT, part of a sister project called MethaneAIR. Chulakadabba and others are using MethaneAIR data to develop and test the MethaneSAT algorithm. The jet has been taking test flights out of Colorado. Soon a Lear 35A, leased and modified by EDF, will start crisscrossing the U.S. looking for methane emissions in work that will complement that of MethaneSAT.

If methane emissions fall rapidly enough to buy time for renewables to grow, it will be time that is almost certainly needed, Wofsy said. Renewables are growing faster than many projected even a few years ago, but they’re still just a fraction of global energy capacity, while signs that the globe is warming around us mount.

“We cannot electrify the entire country, transportation-wise, and go all wind and solar, in the next 10 years,” Wofsy said. “We might aspire to that, but that’s not something you can do in such a short time.”