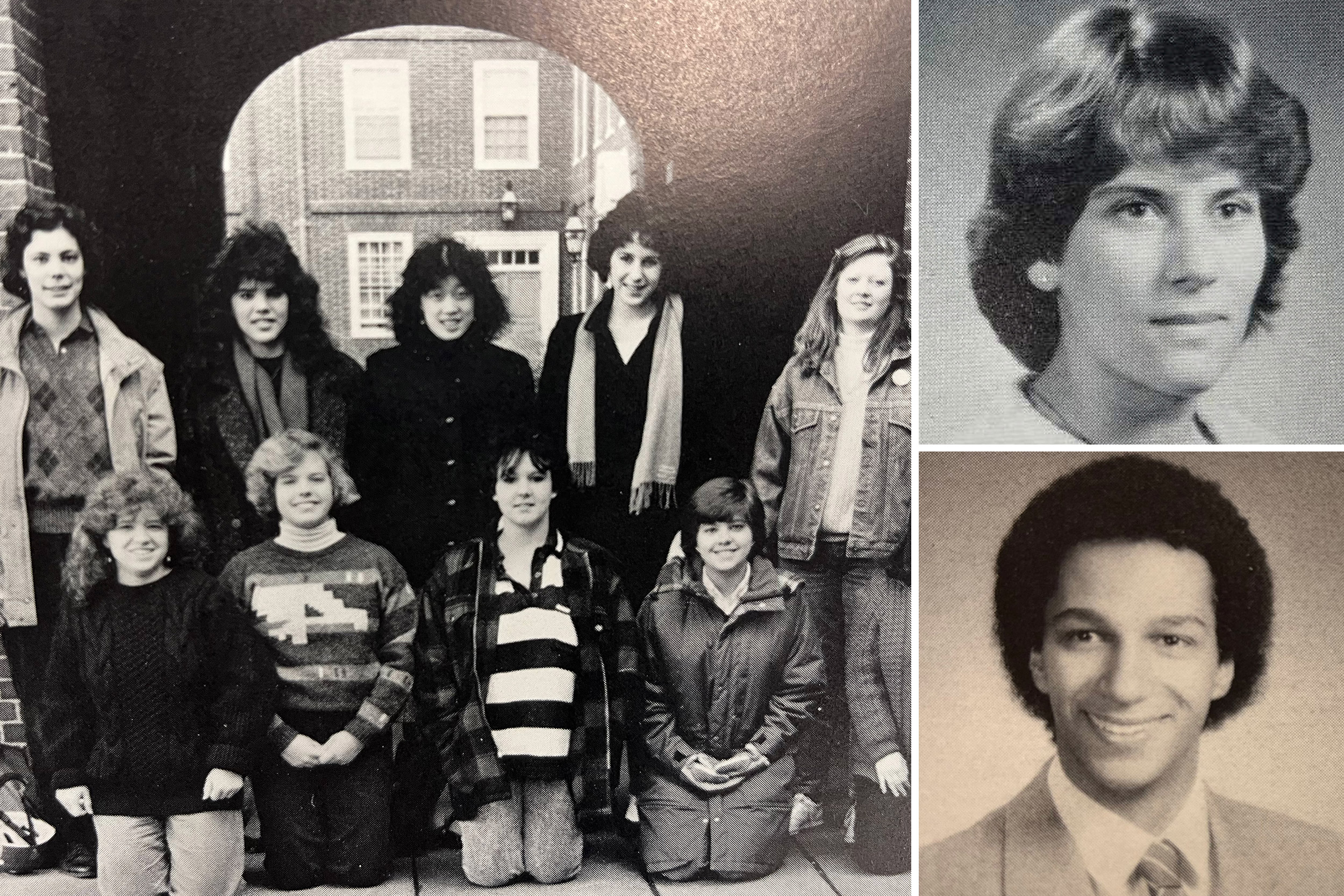

A multifaceted Carolyn Bertozzi was a member of Women in Science at Harvard/Radcliffe (featured in the 1988 yearbook) as well as a keyboardist in a campus band that included Tom Morello (right), the future lead singer of the Grammy-winning rock band Rage Against the Machine.

Images courtesy of Harvard University Archives

A bit of chemistry, a bit of rock ’n’ roll

Nobel laureate Carolyn Bertozzi demonstrated talent for science, creativity even as undergrad

Carolyn Bertozzi says she initially thought she would end up in med school, but when she got to Harvard she fell in love with organic chemistry. So much so, the 1988 graduate recently told the Harvard Crimson, that she wanted “to be left alone on Friday and Saturday night just to read o-chem books in the library.”

That is, except for those weekend nights when she would leave the stacks to play keyboard with the campus band Bored of Education, which featured Tom Morello, future lead singer of the Grammy-winning rock band Rage Against the Machine.

Bored won the Ivy League Battle of the Bands in 1986 — Morello’s senior year — and Bertozzi went on to grad school at Berkeley, professorships at Berkeley and then Stanford, and most recently this year’s Nobel Prize in chemistry for her work on an innovative method for linking molecules. Her work paves the way for breakthroughs in medicine and other life science fields.

Even as an undergraduate in Quincy House, Bertozzi was recognized by faculty and peers for her openness of imagination as well as a remarkable ability to communicate scientific ideas that would set her on the road to scientific superstardom.

“She was just a phenomenal student,” said Joseph Grabowski, then an assistant professor of chemistry in whose lab Bertozzi would cut her scientific teeth. “She was not afraid of taking on things that were brand-new to her, to think about them, and to work through them.”

A native of Lexington, Massachusetts, Bertozzi was born into a family of scientists. Each of her father’s four siblings went into the sciences, and her father, William, taught physics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Beyond the sciences, Bertozzi was a talented athlete and a budding musician in high school.

Bertozzi enrolled in Harvard College in 1984 intent on exploring offerings beyond the sciences. As a talented musician, Bertozzi was a member of several rock bands, including Bored, and eventually found herself drawn more deeply into the sciences.

At that time women in the field continued to be excluded, deterred, and disadvantaged. Bertozzi joined Women in Science at Harvard/Radcliffe (WISHR), which served as a “connective tissue holding the body of women in the scientific community together.”

WISHR established a network of undergraduates who provided tutoring to local schools, invited guest speakers, and participated in planning the Boston Museum of Science’s “Women in Science” exhibit.

As a biology concentrator in her second year, Bertozzi took an organic chemistry course that catalyzed a love for the field. For her senior thesis she designed and built a custom instrument to better understand fundamental aspects of chemistry, the photocaloric calorimeter, earning her the Hoopes Prize.

“In a nutshell, you torture molecules with a photon of light, and you listen to them scream,” Grabowski said. “It’s a way of both monitoring energetics and dynamics in photo-excited systems.”

In addition to her thesis, Bertozzi won an undergraduate teaching award for teaching recitations for Grabowski’s organic chemistry course.

“She was a stellar undergraduate teaching fellow,” he said. “She was willing to take on a challenging idea, understand it, break it down into manageable pieces, and talk about it.”

In addition to her work in the Grabowski Lab, Bertozzi interned in the lab of Professor George M. Whitesides, Woodford L. and Ann A. Flowers University Professor.

“Being an undergraduate in a laboratory that largely consists of postdocs can be a trying experience, because the immediate supervisors are very technically focused,” Whitesides said. “She prospered in that environment. She was very smart, very quick to learn, and very good with working with people.”

Bertozzi graduated summa cum laude in 1988 and went on to graduate school at University of California at Berkeley. There she joined the bio-organic chemistry lab of Mark Bednarski, a Whitesides Lab alumnus, where she studied the synthesis of carbohydrate analogues for biological applications.

After graduating with a Ph.D. in 1993, Bertozzi did postdoctoral research in Steven Rosen’s cell biology laboratory at the University of California, San Francisco, before she accepted an assistant professorship at the University of California at Berkeley. In 2015, Bertozzi went to Stanford to join ChEM-H, an interdisciplinary institute that brings together chemists, engineers, biologists, and clinicians to understand life at the chemical level to improve human health.

At this time her lab invented bioorthogonal chemistry, which allows chemists to bring molecules together safely in a biological setting. This breakthrough enables chemists to develop new medicines, target medicines toward certain tissues, and see biological molecules in living organisms.

“When she first started working on this, I think that most organic chemists thought it probably wouldn’t work, and the biologists felt that chemists shouldn’t muck around in living cells,” Whitesides said. “She tried an idea that really didn’t have any precedent, and it worked, and that’s, of course, the basis of creativity.”

Bertozzi, a former MacArthur Fellow and the first woman to win the prestigious Lemelson-MIT Prize, shared the Nobel with Morten Meldal of the University of Copenhagen and K. Barry Sharpless of Scripps Research for their independent research, which resulted in the development of what is known as click chemistry as well as bioorthogonal chemistry.

“Working with Carolyn was incredibly freeing as a scientist because she is just the most supportive mentor,” said Christina Woo, a former postdoc in the Bertozzi Lab and currently an associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Harvard. “If you went to her with an idea of any sort, she would just say, go do it, and she’ll be your cheerleader.”

As a teacher, Woo now seeks to foster the collaborative and creative atmosphere she felt as a member of the Bertozzi Lab.

“Carolyn did a really good job of including her trainees in everything, from developing their own ideas, to writing the grants, and participating in important conversations when collaborations are forming,” Woo said. “I think she really includes her students at every step in the process, and I try to do the same thing.”