Olha Aleksic launched the “Russia’s War on Ukraine” digital archive in March.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Rushing to save her homeland — or at least its story

Ukrainian bibliographer builds real-time archive documenting Russian war on ground level

Olha Aleksic felt terrified and powerless when Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine in February with missile and artillery attacks and tens of thousands of troops. She feared for the safety of her mother and sister in Lviv and dreaded that her native country might be gone forever in the aftermath.

Many of her colleagues at the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (HURI) and Harvard Library’s Americas, Europe, and Oceania Division wrestled with similar feelings. “The first thing we were asking was, ‘What can we do?’” she said.

Knowing how quickly the war could escalate with the destruction of buildings, neighborhoods, or entire cities, Aleksic, the Petro Jacyk Bibliographer for Ukrainian Collections, launched a project to document the war in real time. She began building the “Russia’s War on Ukraine” digital archive, capturing news stories, videos, data trackers, and social media posts from organizations and media outlets on the ground.

She and HURI colleague Kostyantyn Bondarenko, the project’s technical lead, partnered with web archiving service Archive-It to build the collection. Aleksic plugged instructions into its automatic capture system — such as download this organization’s webpage once a week or capture that media outlet’s tweets every day. It was important to capture data regularly and often because the situation was changing so fast. And in the first days of the war, Aleksic said, any day could be the last day that some part of Ukraine had digital infrastructure.

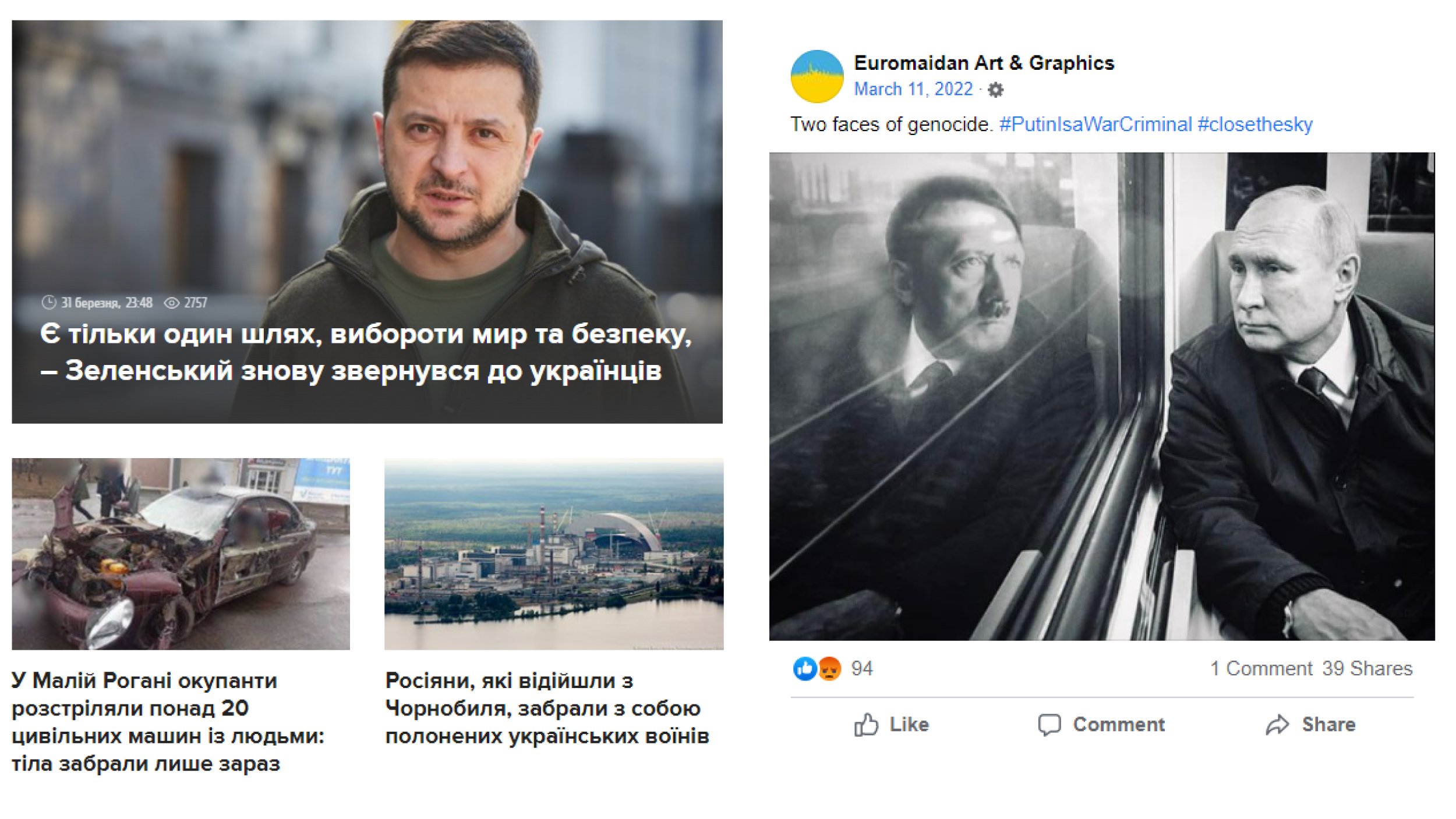

April 1 homepage for Ukrainian news station Channel 24 and a meme on Facebook.

Courtesy of Russia’s War on Ukraine digital archive

When a country is under attack, people don’t immediately think to save images of social media posts, websites, and online news. Such digital materials are actually quite vulnerable, Aleksic said.

“In the United States, we think everything lives in the cloud, and the cloud is forever, and we don’t think about the physical aspect of it,” she said. “We can’t imagine that there would be some kind of disaster tomorrow that could destroy digital infrastructure. But all that data in the cloud is connected to physical objects, and if you’re destroying the physical objects, you can’t access the infrastructure. It’s gone.”

The archive began on March 2, less than a week after Russia’s invasion. It now includes “captures” from nearly 200 people and organizations, including reporting by news outlets, social media pages of political figures like Ukraine President Vladimir Zelensky, websites for cultural organizations with lists of their holdings, pages giving up-to-date information for refugees, and online data posted by local nonprofits counting casualties of the war and sharing results of public opinion surveys. A huge variety of websites stored on servers in Ukraine, Bondarenko said, were targeted for capture — any “might vanish due to infrastructure problems.”

A boarded-up statue in Rynok Square in Lviv. The panels covering the statue read, “We will enjoy the original after our victory.”

Photo by Olha Aleksic

As the war has continued, Aleksic said, concerns have lessened about Ukraine’s infrastructure being wiped out. The project shifted to take on a slightly different purpose, as Aleksic and Bondarenko saw the data being captured as telling the ongoing story of how the war was experienced in Ukraine on a day-to-day basis from the perspective of media, politicians, and refugee aid organizations.

“The first purpose of this project was preservation,” Aleksic said, “but another purpose became having a selection of documents for research and a venue for information from Ukraine that was changing daily or even hourly.”

Elizabeth Kirk, Harvard’s Associate University Librarian for Scholarly Resources and Services, said this sort of archive, with “in-the-moment primary sources and firsthand accounts of conflict, is essential for tracking the progress of a conflict.”

“In addition to the war on Ukraine, there is a war in northern Ethiopia, the remarkable civil upheaval in Iran, and many other global conflicts that current and future historians and political scientists will want to ‘step into’ virtually and understand what was happening beyond the easily documented military and governmental actions,” Kirk said. “With the war on Ukraine, we are incredibly fortunate to have colleagues with the language skills and knowledge of the country who can quickly ramp up this work.

“As we look to the future,” she added, “one of our goals is to diversify our staff to include archivists who can concentrate on this kind of work globally.”

Aleksic took photos of Lviv landmarks the first week of October. Outside town hall, a banner expresses support for soldiers who defended the city of Mariupol and were captured by Russian forces. The opera house is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Photos by Olha Aleksic

For both Aleksic and Bondarenko, who also has friends and relatives in Ukraine, their work will always be somewhat personal.

“Working at [HURI] has always been very fulfilling, but it has taken on added significance in the wake of Russian aggression against Ukraine,” Bondarenko said. “I consider it a great honor to be able to contribute my knowledge and abilities to the Institute’s goals.”

Aleksic said that one of the most powerful stories that emerges from the web archive is the resilience and determination of everyday Ukrainians and the organizations they created to assist their fellow citizens and keep the rest of the world informed.

“There was a springing up, a mass appearance, of websites from organizations that were trying to help,” she said. “As there are air raids and bombings and horrible tragedies, Ukrainians were doing their part to inform people about what’s happening. For this society to be so resilient, so self-organized, to create and maintain these sites, it speaks very loudly.”

Aleksic, who recently was able to return to Ukraine to see friends and family, said capturing everything that they have with the digital archive wasn’t the same as being in Ukraine with her community. But for seven months, it did ease her feeling of powerlessness to some degree.

“It does help to know you’re useful in some respect,” she said. “There’s a feeling that it’s never enough — but it does help.”