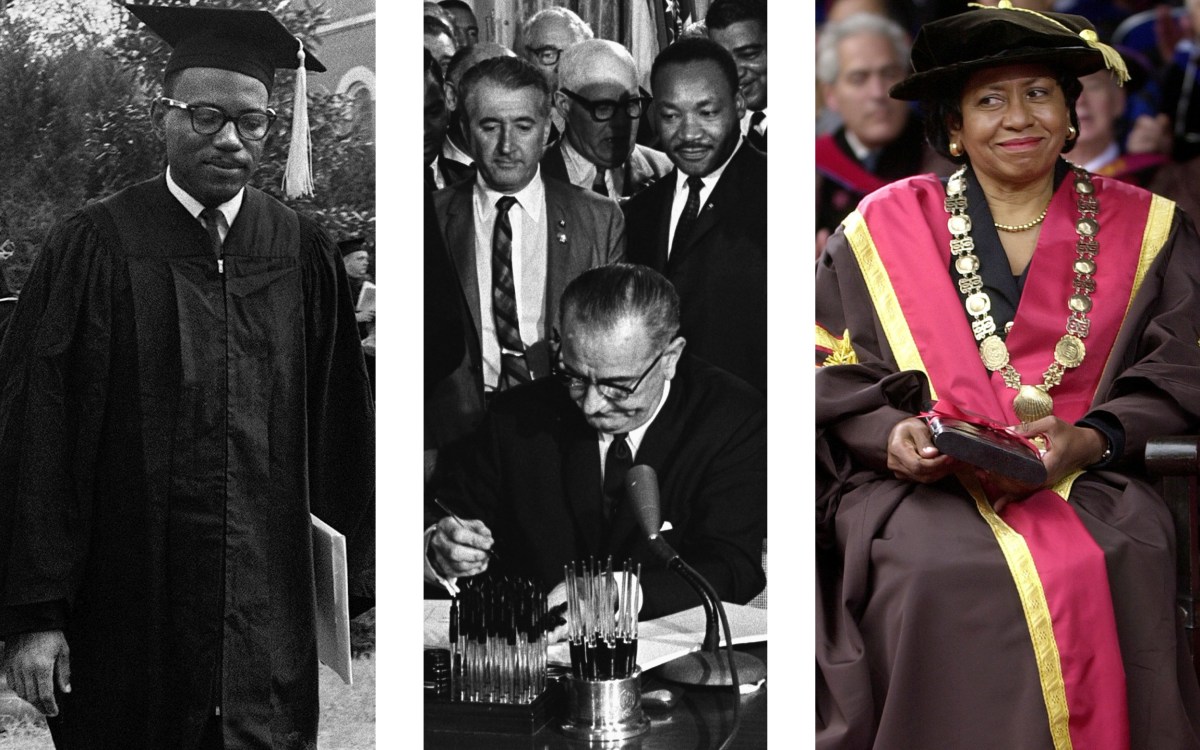

Protests by University of California and Michigan students in 1996 and 2006 responding to state bans of affirmative action.

AP file photos

Michigan, California speak from experience in briefs supporting Harvard

Schools have struggled in diversity efforts since bans on race-conscious admissions

How might America’s colleges and universities be changed by a Supreme Court ruling that ends race-conscious admissions? Data from the state university systems in California and Michigan paint a troubling picture.

Both were forced to stop considering race after voters called for statewide bans. That led to a precipitous decline in campus diversity, senior officials at the schools said in briefs filed with the court in support of Harvard and the University of North Carolina.

These briefs contradict statements Students for Fair Admissions made Monday in its argument against Harvard before the Supreme Court, in which the group’s lawyers claimed that the experiences of Michigan and California show how a university can achieve effective race-neutral alternatives. In fact, both schools have found these alternatives lacking, officials said.

Likening the university to an “experiment in race-neutral admissions,” Michigan officials said that the school’s struggle to maintain diversity underscores how a limited consideration of race is necessary for colleges and universities to achieve the educational benefits that arise from a diverse student body.

Even with what officials described as “extraordinary” recruiting efforts, enrollment among Black and Native American students at Michigan has fallen by 44 percent and 90 percent, respectively, since 2006, when consideration of race was banned. These declines come despite admissions officers’ consideration of a candidate’s socioeconomic background and whether they would be the first in their family to attend college.

Michigan has been a prominent voice in the case law concerning the constitutionality of race-conscious admissions, including in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003). In that case, the Supreme Court reaffirmed that obtaining the educational benefits of a diverse student body is a “compelling state interest” that can justify using race as one factor among many in a holistic consideration of each applicant. This principle “remains just as true today,” Michigan officials say.

Like Michigan, the University of California implemented a wide variety of race-neutral approaches to continue attracting or even increasing student diversity across its 10 campuses after voters adopted Proposition 209 in 1996, which banned consideration of race in college admissions.

While UC has had some success expanding economic and geographic diversity among its more than 290,000 students, it has struggled to enroll a student body that is “sufficiently racially diverse to attain the educational benefits of diversity,” university officials said in their brief.

First-year enrollment of students from underrepresented groups has fallen “precipitously” systemwide and has declined by 50 percent or more at UC’s most selective campuses, where African American, Native American, and Latino students are already underrepresented and widely report struggling with feelings of racial isolation, UC officials wrote.

In the aftermath of the ban, falloff was particularly dramatic at UCLA and UC Berkeley. In 1995, African Americans made up 7.13 percent of first-year students at UCLA but only 3.43 percent in 1998, the year California’s ban took effect. At Berkeley, 6.32 percent of students were African American in 1995 but just 3.37 percent in 1998. Latino students made up 15.57 percent of Berkeley first-years in 1995 and only 7.28 percent in 1998, despite African American and Latino students representing 7.5 percent and 31 percent, respectively, of the state’s public high school graduates in 1998.

Even as California has grown more diverse, these racial disparities persist. In 2019, 52.3 percent of California public high school graduates identified as Latino, while 24.4 percent identified as white, 13.6 percent as Asian, 5.5 percent as African American, and 0.5 percent as Native American. Yet only 25.4 percent of first-year undergraduates across UC’s nine college campuses identified as Latino, 3.87 percent as African American, and 0.42 percent as Native American, according to UC’s brief.

California’s difficulties since the late 1990s to achieve racial diversity demonstrate “that highly competitive universities may not be able to achieve the benefits of student-body diversity through race-neutral measures alone,” officials said, and so “must retain” the ability to consider race in a limited fashion, as the Supreme Court has permitted.

“In a nation where race matters, universities must maintain campus environments that enable them to teach their students to see each other as more than mere stereotypes,” UC wrote. “Succeeding at that endeavor is crucial to preparing the next generation to be effective citizens and leaders in an increasingly diverse nation.”