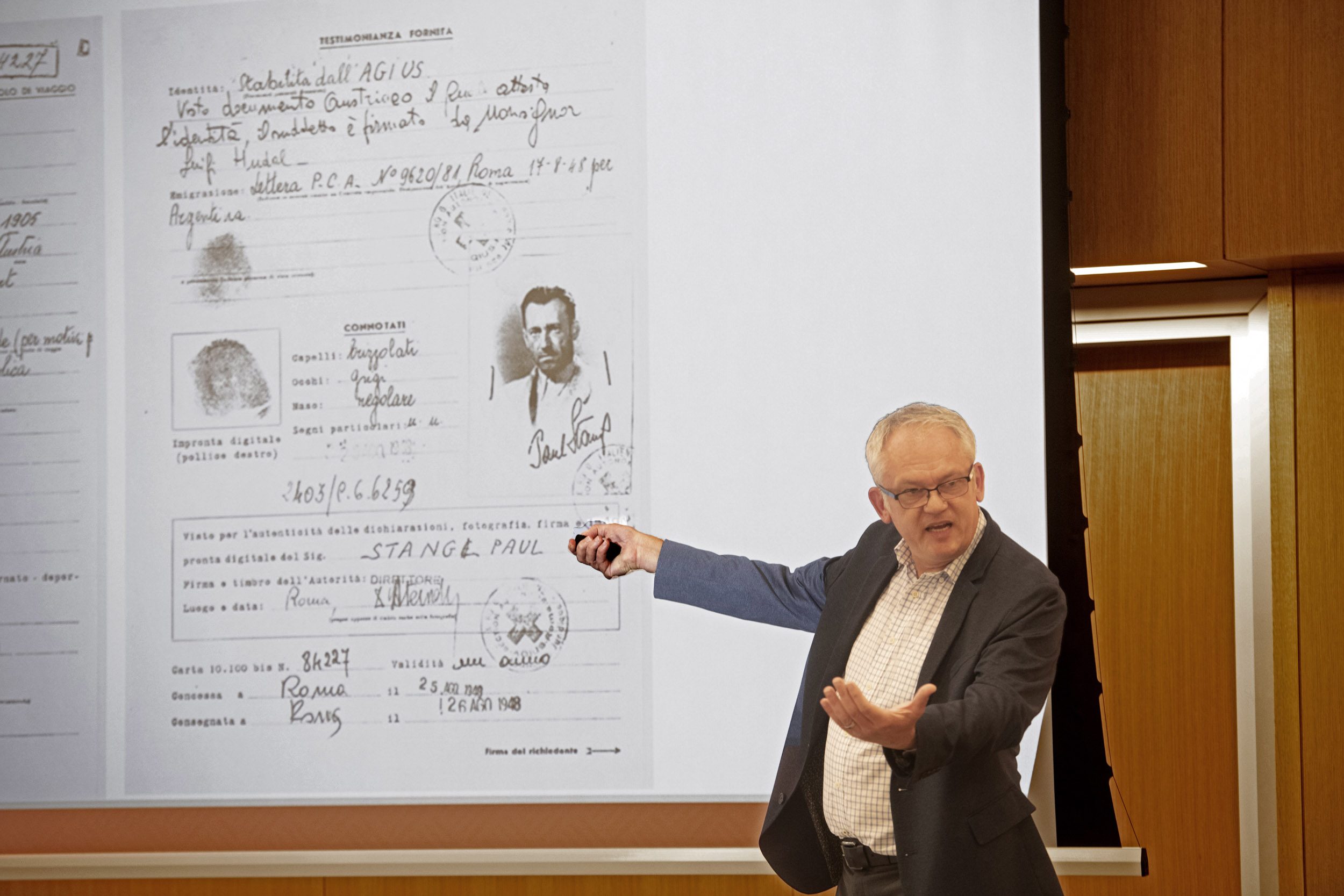

Gerald J. Steinacher shared the latest findings from his research in the Vatican archives, which showed that the Vatican and the International Committee of the Red Cross worked together to help Nazi war criminals escape justice.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Gift given, one left behind

Holocaust lecture, funded by refugees saved by Harvard students, warns anew on bigotry, authoritarianism

Walter Pick was 22 years old when he arrived at Harvard in September of 1939, escaping from his native Czechoslovakia hours before the country fell under Nazi occupation. He, along with 15 other young men from Austria and Germany, arrived as refugees from German persecution on scholarships funded by Harvard undergraduates.

Karen Pick, Pick’s daughter, came to campus on Thursday evening to pay tribute to the humanitarian efforts of those Harvard students. Walter graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1942, and in 1992, he and the surviving Harvard Refugee Fellows started a fund for a lecture series on the Holocaust to honor the memory of the undergraduates and faculty who had helped them. He died in 2002.

Underwritten by the fund, Thursday’s lecture featured Holocaust historian Gerald J. Steinacher, James A. Rawley Professor of History, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and author of “Nazis on the Run: How Hitler’s Henchmen Fled Justice.” Pick found attending the lecture her father had started 30 years ago touching, if sadly still altogether too relevant.

In his lecture “The Pope Against Nuremberg: Nazi War Crime Trials, the Vatican, and the Question of Postwar Justice,” Steinacher shared the latest findings from his research in the Vatican archives, which Pope Francis opened in March 2020. He has also done research in the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva.

Archival documents from both the Vatican and the International Committee of the Red Cross showed that the two institutions worked together to help Nazi war criminals, including Adolf Eichmann and Josef Mengele, flee Europe and escape justice. Their behavior was driven by widespread anti-Semitism in the Catholic Church and a fear of Communist ideologies, said Steinacher.

“As international- and American led-trials against Nazi war criminals began, the Catholic Church worked hard to shield perpetrators from prosecution,” said Steinacher. “At the same time, the Vatican institution helped Nazi war criminals escape overseas, where they were safe from extradition.”

Karen Pick (far left) attends the lecture her father started 30 years ago.

Steinacher questioned the position of Pius XII, the wartime pope, against the Nuremberg trials. In 1948, Pius XII called for an end to war crime trials under the motto of “forgive and forget.”

“The world should just forgive and forget Germany’s war crimes and instead help to rebuild the country, was the message by the pope,” said Steinacher. “In the pope’s crusade against Nuremberg, perpetrators were quickly forgiven, and the victims quickly forgotten.”

For Professor Kevin J. Madigan, Winn Professor of Ecclesiastical History and faculty dean of Eliot House, the lecture highlighted the need to continue to explore and research the Holocaust.

“The Holocaust was, or required, the seizing of power, the cooperation of a massive bureaucratic apparatus, and the use of modern technology and the weaponizing of prejudice, which a regime could use at a time of global disintegration for unspeakable destruction,” said Madigan. “As those are features of modernity, and are still with us, we remember for the future, to make ourselves alert to the possibility of catastrophe, so that we might stop tragedy long before it starts to unfold.”

Pick agreed that the talk felt illuminating and necessary, but those feelings were mixed with gratitude for those who saved her father.

“My father’s life was saved because of the efforts of a group of Harvard students,” said Pick before the talk that took place at Harvard Divinity School. “Just like my father, those students were in their 20s, and yet they did what they could to save people. What they did was fantastic. They saved people’s lives.”

The student refugees in addition to Pick were: Ernst Berliner, M.A. ’41, Ph.D. ’43; Karl Deutsch, Ph.D. ’51; Regula Frankl (Davis) ’42; Kurt Hertzfeld ’41, M.B.A. ’42; Hans Imhof ’42; Rachel Kestenberg ’40; Herman Noether, M.A. ’40, Ph.D. ’43; Walter Robichek ’42, M.P.A. ’44; George Rohrlich, Ph.D. ’43; Milos Safranek ’42; Herbert Sonthoff, M.A. ’42; George Springer ’42, Ph.D. ’54; Walter Stettner, Ph.D. ’44; Klemens von Klemperer, M.A. ’40, Ph.D. ’49; and Thomas Winner ’42, M.A. ’43.

The initiative to bring student refugees to Harvard was led by Philip Bagby ’39; Alice Burke ’39; Robert Lane ’39, Ph.D. ’50; Irving London ’39, M.D. ’43; Lucille Radlo (Gray) ’39; Robert Ridder ’41; and Abba Schwartz, LL.B. ’39.

A retired elementary teacher, Pick works in an adult learning program her mother started in 2003 in Fitchburg. The event left her with a renewed sense of the value of both the gift given to her father and the other refugees and the one they left behind.

“The program was started to teach lessons from the Holocaust,” Pick said. “It seems to me that we could use some lessons.”