Chang Duong/Unsplash

Turns out it’s not who you know that determines economic success

Big-data study by Raj Chetty, team shows whom you interacted with while growing up is more important

When it comes to economic success, the big thing isn’t who you know, but whom you interacted with as you grew up. That’s the message of a sweeping, two-paper study that examined privacy-protected data drawn from 21 billion Facebook connections covering 84 percent of U.S. adults ages 25 to 44.

In “Social Capital I: Measurement and Associations with Economic Mobility,” published Monday in Nature, William A. Ackman Professor of Public Economics Raj Chetty and his team looked at privacy-protected data from Meta, formerly known as Facebook, to analyze social networks and to construct and analyze distinct measures of social capital for each ZIP code, high school, and college in the U.S. The researchers, who, with Chetty, included Johannes Stroebel and Theresa Kuchler of New York University and Matthew O. Jackson of Stanford and the Santa Fe Institute, found that children who had social relations with peers from higher-income families ended up with higher incomes themselves.

“What really matters are interactions that influence people,” said Chetty, who is also the director of Opportunity Insights, which uses big data to study economic opportunity. In 2018, the group released the Opportunity Atlas, which analyzed the national landscape on economic mobility and indicated significant variation in mobility outcomes across neighborhoods in the U.S.

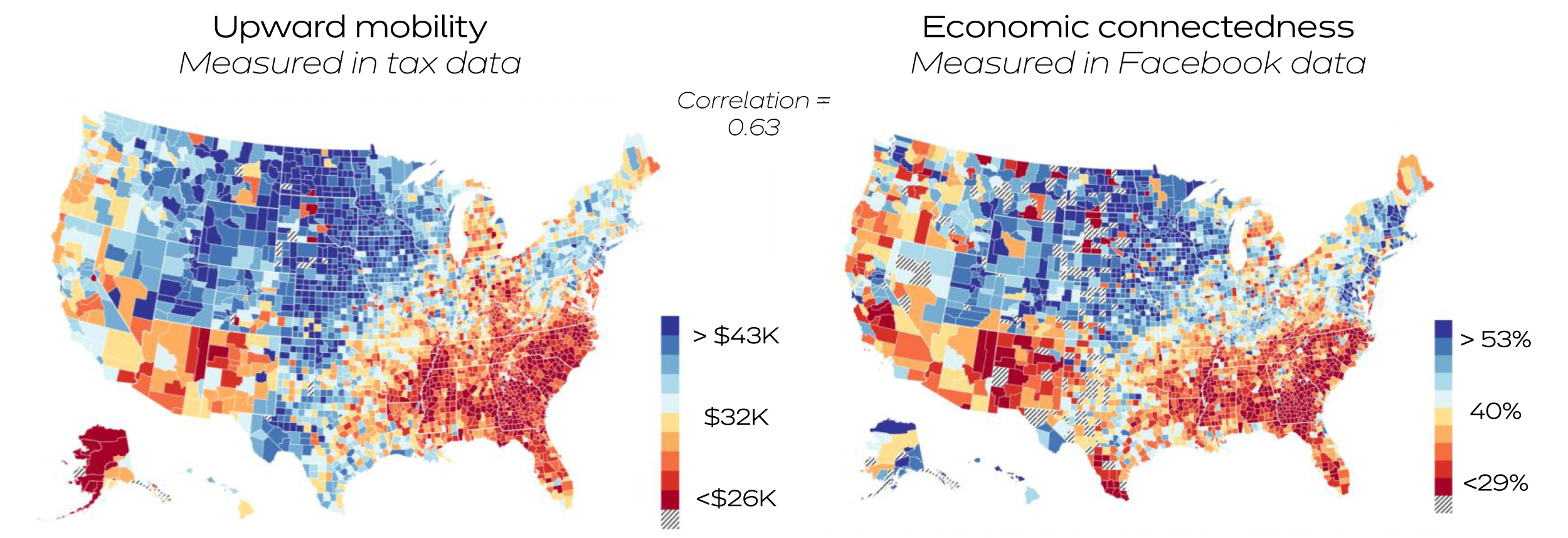

Upward mobility tends to reflect economic connectedness

Left: County level map of upward mobility, defined as the average income in adulthood for children from low-income families. Right: County level map of economic connectedness, defined as twice the share of friends with above median socioeconomic status among people with below median socioeconomic status.

Opportunity Insights

This latest work on social capital in the U.S., perhaps the most comprehensive study ever done on the topic, was inspired by this earlier work on neighborhood effects and on what drives economic mobility. Of particular importance in the latest findings is what Chetty calls “cross-class interaction,” that is, relationships between children from different socio-economic groups. This is “very strongly related to children’s chances of rising out of poverty and their economic mobility,” he said.

Such interactions are about more than one-off opportunities, he stressed. “It’s not just about job referrals,” said Chetty. “It’s not like if you show up at age 18 in a more connected place, somebody connects you to a better job.

“It’s about growing up from childhood in a more connected area,” he said. “It shapes your aspirations. It shapes the things that you think about, the career paths you think about pursuing. If you’ve never met anybody who’s gone to college, you probably don’t think about applying to college or applying to a place like Harvard.”

But simply throwing children together — in social experiments as busing did — is not the answer.

In their second paper, “Social Capital II: Determinants of Economic Connectedness,” Chetty and the other researchers asked, “Given that connectedness seems to matter, what determines it?

“It’s not just about exposure,” Chetty said. “It’s not just about admitting a more diverse class at Harvard. It’s about actually getting people to interact at Harvard or in their high school or in their neighborhood.”

The Social Capital II study revealed that children of lower socioeconomic status are often less likely to connect with those of higher status, a so-called “friending bias” that appears even when both groups are exposed to each other.

This bias, the researchers found, is more likely to occur in certain settings. In churches, faith-based groups, and recreational groups, for example, people exhibit less friending bias. However, in neighborhoods, high schools, and colleges, “You’re much more likely to spend time with people who are more like you than people from a different socioeconomic class,” said Chetty.

“It shapes your aspirations. It shapes the things that you think about, the career paths you think about pursuing.”

Raj Chetty, William A. Ackman Professor of Public Economics

Bias in this sense is not a personal preference, he said. Instead, it’s more likely shaped by institutional practices — such as high school tracking that sets some students toward college and others toward vocational school. Such practices are more prevalent in large institutions, exacerbating the problem even in situations where people from many different groups are exposed to each other.

“In large settings, there’s a tendency to split, and in small groups there’s a tendency to come together,” he said. “That’s something we can work on to create more meaningful cross-class interaction and cross-race interaction.

As part of that process, on Monday, Opportunity Insights launched the Social Capital Atlas, which allows users to look up schools and neighborhoods and view measures of social capital including economic connectedness, social cohesion, and civic engagement. By providing previously unavailable information, this tool also can enable local action, or “targeted intervention.”

For Drew Johnston, one of the papers’ authors, the tool confirmed some of the group’s theories about smaller groups. “Growing up, I lived in a small town, where everybody attended the same school,” said Johnston, a fourth-year Ph.D. student in economics. “As a result, I wasn’t shocked to see my hometown show up as a place with relatively little bias compared to places with more segregated housing and schools.”

“What we’re learning is it’s not just about the resources people have,” concluded Chetty. “What this is suggesting is the sociological phenomenon of how people make decisions from childhood, what their aspirations are, what they choose to do, might be quite important.”