Not even high-wage opportunities seem to lure young people from moving more than 100 miles from where they grew up, according to a new report.

iStock by Getty Images

Key to income inequality fight? Location, location, location

Study shows young workers resist moving far from home even for higher pay, so answer may be to move better jobs closer to those who need them most

It would seem a reasonable assumption that higher wages would draw young adults to a city or a region. But the vast majority of young people don’t move far from home, and even the offer of more money appears to have a very small impact on their willingness to relocate, a new study by Harvard researchers has found, suggesting that economic planners looking to fight income inequality would do better to relocate better jobs closer to the people who need them.

In their working paper, “The Radius of Opportunity: Evidence from Migration and Local Labor Markets,” Economics Professor Nathaniel Hendren and Ben Sprung-Keyser, a Ph.D. student in the department, utilized U.S. Census Bureau information to study the movement of young adults. Along with Sonya Porter, a principal sociologist and demographer with the Bureau’s Center for Economic Studies, they found that that 80 percent of all young adults at age 26 had moved less than 100 miles from where they grew up, and just 10 percent moved more than 500 miles away. For example, the working paper notes, “children growing up in Dubuque, IA, are three times more likely to move to nearby Des Moines or Waterloo than to Chicago, just slightly further away.”

While higher-wage opportunities could be expected to lure more of those young adults to new territory, the paper found the effect limited. In fact, an increase of $1,600 in annual salary only resulted in a 1 percent uptick.

“Young people don’t move far from their home,” said Hendren, who is also co-director of Opportunity Insights and co-director of Policy Impacts, both Harvard-based nonpartisan, not-for-profit organizations. “They do move in response to higher wages, but we argued that the effects are not that large in general.”

“People certainly respond to changes in wage opportunities, but those people are a fraction of the population, and they still tend to move close by,” said Sprung-Keyser, another co-director of Policy Impacts.

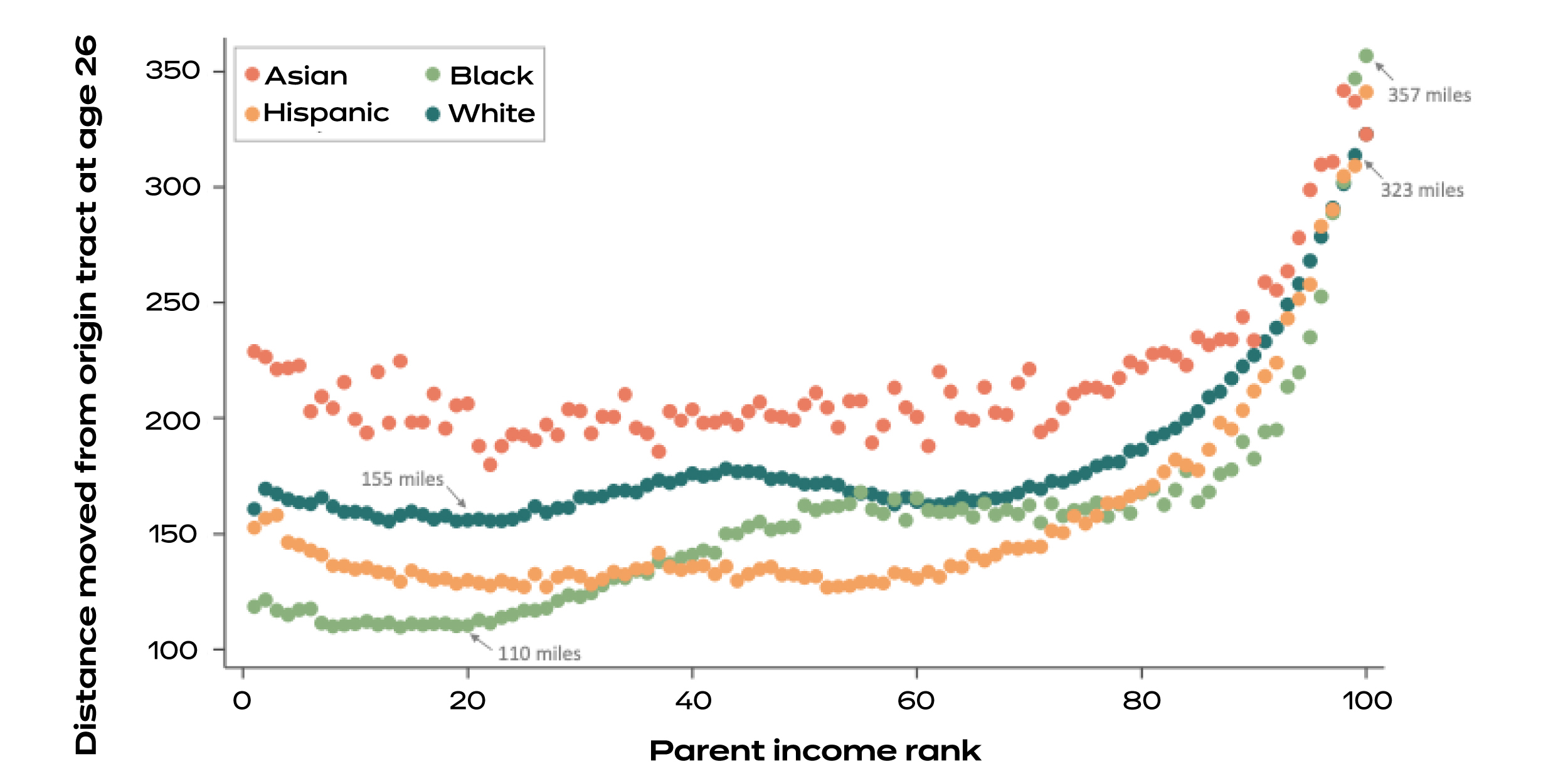

In addition, the study found differences in migration patterns, even within the age demographic. Young Black and Latino adults tended to move shorter distances than young white adults, and they move to different places.

“The most common destinations for Black young adults are Atlanta, Houston, and D.C.,” said Hendren. “The most common destinations for young white adults are the big three cities — New York, Chicago, and L.A. — but also Denver, Colorado, which is not in the top 10 for any other racial group.”

The income level of these young adults’ original families appears to play a major role, even offering what Hendren calls a rare reversal.

“In the data involving young adults from low-income families, we see that Black and Hispanic young adults move a shorter distance than white young adults, even looking within the set of low-income families,” said Hendren. “But when you look at families in the top 1 percent, you actually see a convergence and a bit of a reversal of these race gaps. Black young adults born into the top 1 percent move 30 miles farther on average than white young adults born to people in the top 1 percent.”

Average distance traveled by race/ethnicity and parental income

This figure presents the average distance moved between childhood (measured at age 16) and young adulthood (measured at age 26) separately by parental income and the child’s race/ethnicity.

“The Radius of Opportunity: Evidence from Migration and Local Labor Markets”

What the data does make clear is that wages alone do not heavily impact where young adults move, with the result that benefits tend to accrue to the workers already in place. “Imagine a scenario where wages go up in in New York,” said Hendren. While one would expect “people coming from across the country to go there and pick up those benefits,” what they found was different: “If wages go up by $1 in New York, 99 percent of the people that get that extra $1 would’ve been in New York anyway.

“When we look across the U.S. and see geographic inequities in labor market outcomes, those are translating into differences and intergenerational opportunities for kids,” he said. “And so if we’re thinking about trying to improve economic outcomes through policies that affect the labor market and interested in trying to improve outcomes of kids growing up in a particular area, we really need to target the areas where they’re growing up and try to improve the labor markets in those areas.

“If you do increase wages in a place, there’s a lot of people that benefit from that,” he stressed. However, “it matters where those wages increase. If you want to improve outcomes for people growing up in Chicago, you want to draw a small radius around Chicago and try to get the wages to increase there.”

“If you’re looking to provide economic support to people who grew up in a given area, the right approach is to invest in the area itself,” added Sprung-Keyser. “Chances are they’re still living nearby.”