Frame for Albert Moore’s “Study for Blossoms” (1881), before and after toning.

Courtesy of Harvard Art Museums

Make it new (by making it old)

Harvard Art Museums conservator Allison Jackson explains how she gilded, aged frame on 19th century painting on display

Allison Jackson couldn’t stop long to chat. She was adding an impossibly thin layer of gold leaf to a small wooden frame in a conservation lab on the Harvard Art Museums’ bright, vaulted fifth floor. As she worked, the “oil size” — the adhesive she’d applied the night before — was starting to dry. “Once it has set up for 12 hours the size is only tacky for a short window,” she said.

Carefully, the assistant frames conservator at the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies lifted tiny pieces of the decorative gold from a small booklet with the help of a soft brush she repeatedly touched to her cheek. The oil from her face, she explained, helps the brush stick to bits of an 18.5-karat square sheet of gold leaf that’s only 1/250 thousandth of an inch thick. Making sure not to breathe too hard to ensure the delicate leaf didn’t float away, she carefully brought her gilt-tipped brush down to the frame, gently pushing the gold into the small carved crevices, and smoothing it out with another, slightly stiffer brush.

When done, Jackson would let the frame sit for 10 days to “fully cure,” then begin muting its glow.

“Once gilded the frame looks like a gold bar, so it has to be toned back to make it look like it’s 150 years old,” said Jackson, who would go on to apply a layer of glue followed by shellac and a thinned-out layer of paint to the frame to artificially age and “dirty” its newly glided surface. “The process works to beautifully mellow the harshness of the lemony green gold that Moore choose for his frames.”

Jackson was referring to the 19th-century British artist Albert Moore, and she was putting the shining touches on a frame she helped recreate for an early version of the lush Moore painting “Study for ‘Blossoms’” (c. 1881), on view in the museums’ gallery The Pre–Raphaelites and Their Legacy.

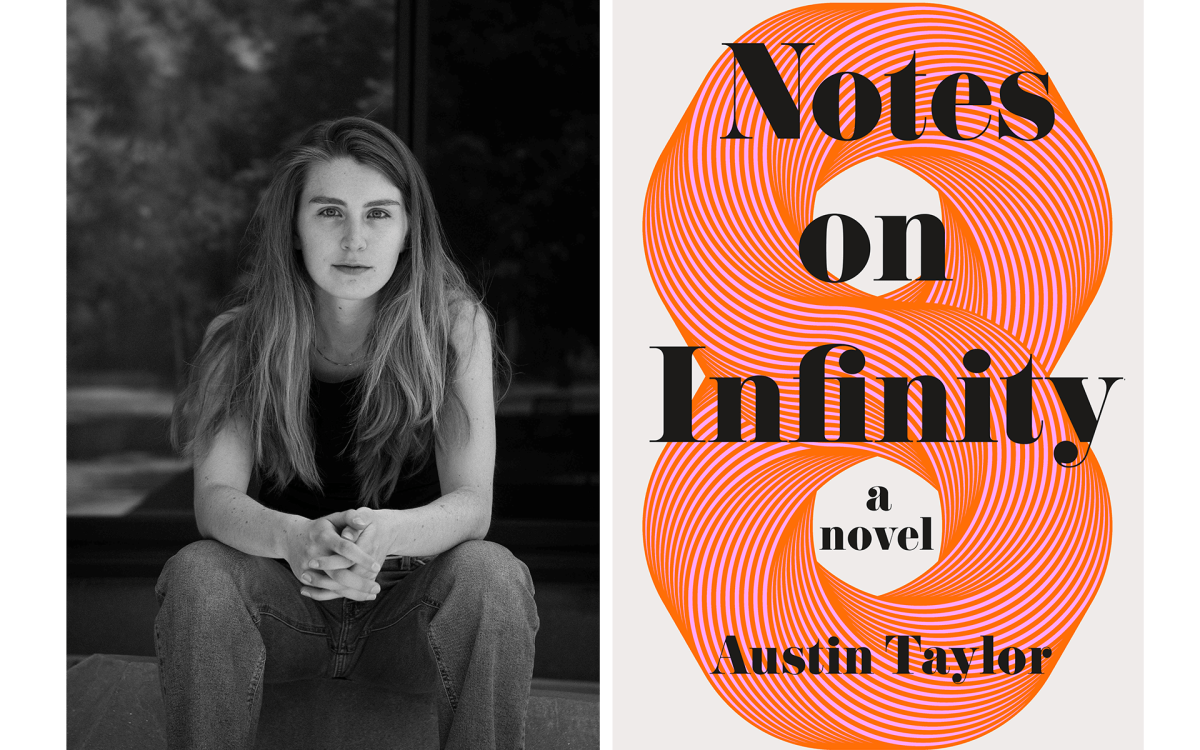

“Once gilded the frame looks like a gold bar, so it has to be toned back to make it look like it’s 150 years old,” said assistant frames conservator Allison Jackson.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Allison joined forces with her mother Sue in 2014 to gild a frame for the 17th-century painting by Paolo Finoglia, “Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife.”

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

[gz_ws_audio_player mp3=”344756″ player_option=”noimage” layout=”article-width” title=”Mother-daughter%20conservators%20Sue%20and%20Allison%20Jackson%20talk%20about%20their%20craft” transcript=”%5BSUE%5D%3Cp%3E%0AMy%20name%20is%20Sue%20Jackson%2C%20and%20I’m%20a%20gilding%20conservator.%3Cp%3E%3Cp%3E%0A%0A%5BALLISON%5D%3Cp%3E%0AMy%20name%20is%20Allison%20Jackson%2C%20and%20I%20am%20also%20a%20gilding%20conservator.%20I%20work%20at%20the%20Harvard%20Art%20Museum’s%20as%20their%20frame%20conservator%2C%20and%20I%20have%20private%20practice%2C%20also.%3Cp%3E%3Cp%3E%0A%0A%5BALLISON%5D%3Cp%3E%0ACan%20you%20remind%20me%20how%20you%20got%20into%20this%20line%20of%20work%3F%3Cp%3E%3Cp%3E%0A%0A%5BSUE%5D%3Cp%3E%0AI%20always%20admired%20artists%20the%20most.%20And%20to%20find%20a%20niche%20for%20myself%20where%20I%20could%20fit%20into%20the%20art%20world%20was%20always%20a%20goal.%20And%20on%20the%20cape%20in%20Cotuit%2C%20there%20was%20a%20museum%20exhibit%20on%20frames%20and%20a%20weekend%20workshop%20on%20gilding.%20I%20took%20that%20workshop%20and%20ended%20up%20apprenticing%20from%20there%20and%20it%20just%20became%20part%20of%20me%20and%20what%20I%20sought%20out%20to%20do%20and%20find%20out%20as%20much%20as%20I%20could%20about%2C%20and%20work%20at.%3Cp%3E%3Cp%3E%0A%0A%5BALLISON%5D%3Cp%3E%0ACan%20you%20explain%20why%20you%20would%20want%20to%20gild%20something%20rather%20than%20simply%20paint%20it%20with%20gold%20paint%3F%3Cp%3E%3Cp%3E%0A%0A%5BSUE%5D%3Cp%3E%0AWell%2C%20I%20may%20be%20a%20little%20biased.%20But%20the%20appearance%20of%20gold%20is%20just%20so%2C%20it%20just%20has%20a%20warm%2C%20soft%20glow%20to%20it%20that%20can’t%20be%20replicated%20with%20paint.%3Cp%3E%3Cp%3E%0A%0ASo%2C%20Alli%2C%20what%20do%20you%20remember%20about%20the%20gilding%20studio%20back%20when%20you%20were%20young%3F%3Cp%3E%3Cp%3E%0A%0A%5BALLISON%5D%3Cp%3E%0AYou%20had%20a%20beautiful%20space%20that%20really%20transformed%20over%20the%20years%20from%20a%20small%20makeshift%20space%20to%20a%20gorgeous%20studio%20with%20skylights%3B%20and%20more%20and%20more%20people%20came%20to%20work%20for%20you.%20Originally%2C%20seeing%20you%20working%20so%20hard%20and%20bent%20over%20a%20frame%2C%20I%20felt%20like%20I%20would%20never%20want%20to%20go%20in%20that%20direction%20or%20do%20the%20same%20thing.%20And%20I%20think%20I’ve%20said%20that%20to%20you%20before%20even%20as%20a%20kid.%20It%20was%20really%20once%20I%20got%20in%20there%20and%20kind%20of%20started%20doing%20some%20of%20it%20for%20myself%20here%20and%20there%2C%20it%20was%20your%20positive%20encouragement%2C%20and%20saying%20%E2%80%9CWow%2C%20you’re%20really%20good%20at%20this%2C%E2%80%9D%20is%20how%20I%20kind%20of%20ended%20up%20following%20in%20your%20footsteps.%3Cp%3E%3Cp%3E%0A%0A%5BSUE%5D%3Cp%3E%0AWell%2C%20I%20can%20tell%20you%2C%20Allison%2C%20that%20it%E2%80%99s%20been%20%E2%80%A6%20I%E2%80%99m%20gonna%20cry%20(laughter).%3Cp%3E%3Cp%3E%0A%0A%5BALLISON%5D%3Cp%3E%0AMe%20too%20(laughter).%3Cp%3E%3Cp%3E%0A%0A%5BSUE%5D%3Cp%3E%0AAllison%2C%20I%20do%20remember%20when%20you%20told%20me%20that%20working%20on%20frames%20was%20really%20boring.%20And%20to%20see%20what%20you’re%20working%20on%20now%2C%20and%20the%20projects%20you%20take%20on%20and%20the%20results%20that%20you%20make%20happen%20is%20just%20so%20gratifying.%20It’s%20been%20amazing%20to%20see%20that%20all%20you’ve%20done%20and%20how%20far%20you’ve%20come%20and%2C%20and%20to%20know%20that%20the%20work%20that%20I%20put%20into%20learning%2C%20that%20I’ve%20been%20able%20to%20pass%20on%20some%20of%20that%20knowledge%20to%20you%20and%20have%20you%20benefit%20from%20it.%20And%20learn%20more%20from%20you%2C%20too%2C%20and%20what%20you’ve%20learned.%3Cp%3E%3Cp%3E%0A%0A%5BALLISON%5D%3Cp%3E%0AYou’ve%20been%20incredibly%20generous%20over%20the%20years%20with%20your%20time%20and%20knowledge%2C%20and%20I%20am%20very%20happy%20in%20the%20place%20that%20I%20am%20in%20the%20field%2C%20and%20I%20give%20you%20a%20lot%20of%20credit.%3Cp%3E%3Cp%3E%0A%0A%5BSUE%5D%3Cp%3E%0AWell%2C%20I%20couldn’t%20be%20more%20proud%20of%20you%20and%20the%20work%20that%20you%20do.%20And%20it’s%20just%2C%20it’s%20very%2C%20very%20gratifying.%20You%20do%20a%20fabulous%20job%20and%20I%20love%20you.%3Cp%3E%3Cp%3E%0A%0A%5BALLISON%5D%3Cp%3E%0A(Laughter)%20I%20love%20you%20too.” /]

Jackson had the chance to see “Blossoms” in person while visiting the Tate Britain’s collection in London during a 2016 fellowship at Knole, a country house in Kent, England, owned by the National Trust. Like Harvard’s painted study, the piece at the Tate reflects Moore’s interest in ancient Greek sculpture and Japanese art and depicts a woman draped in a flowing robe surrounded by pale Japanese cherry flowers. At the time Jackson also visited London’s Guildhall Art Gallery to see Moore’s “Pomegranates,” which is encased in a frame the artist himself designed. Conservators at each museum later helped Jackson with her artistic sleuthing as she researched the kind of frame that would best fit the Harvard piece.

“The frame on the Harvard painting was not appropriate, and we wanted to make a frame that looked like something Moore had created,” said Jackson, who worked with an outside carpenter to design the piece. “We realized ‘Pomegranates’ offered us the perfect example with its classical ornament and similar size, so we modeled our new frame after that.”

For Jackson, a frame is as important as the work it holds. She considers restoring a frame a way to honor the artist and his or her output, and credits her mother, Sue Jackson, for getting her interested in the field.

Jackson grew up in Harvard, Massachusetts, watching her conservator mother working on frame and gilding projects in her small home studio behind their garage. She studied fine art at the University of Vermont and later trained with a master carpenter in Hawaii. She began her career at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in 2006 and was later hired by Harvard to help restore and refurbish about 150 frames between 2012 and the museums’ reopening, following a major renovation, in 2014. As part of that preparation work, Jackson and her mother joined forces, gilding a recreated frame for the 17th-century Italian painting by Paolo Finoglia “Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife.”

“It was great being able to work with my mother again on that project,” said Jackson. “And even with this Moore painting I made many calls throughout the process to talk with my mom and solicit her advice. I am so happy about where I am in the field today, and I give my mother so much credit for that.”