“The most politically salient part of inflation is gasoline prices. … The good news is that part of inflation is likely to level off or come down,” says economist Jason Furman.

AP Photo/Marta Lavandier

Things may look shaky, but recession isn’t certainty

Economist says amid tumbling stocks, rising prices, scrambling Fed much will depend on how consumers react

It feels to many as if the economy is all over the place. The stock market is sliding, and new Labor Department figures this week show soaring inflation slowed last month to an 8.3 percent rate while prices remained at a four-decade high. The Fed is aggressively raising interest rates to slow spending and bring down inflation. The most recent news for workers, on the other hand, has been good, with April unemployment at a low 3.6 percent amid solid job and wage growth. The big question on everyone’s mind: Are we headed toward recession? Jason Furman, Aetna Professor of the Practice of Economic Policy at Harvard Kennedy School and the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, spoke with the Gazette about the recent stock market instability and prospects for serious economic downturn. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

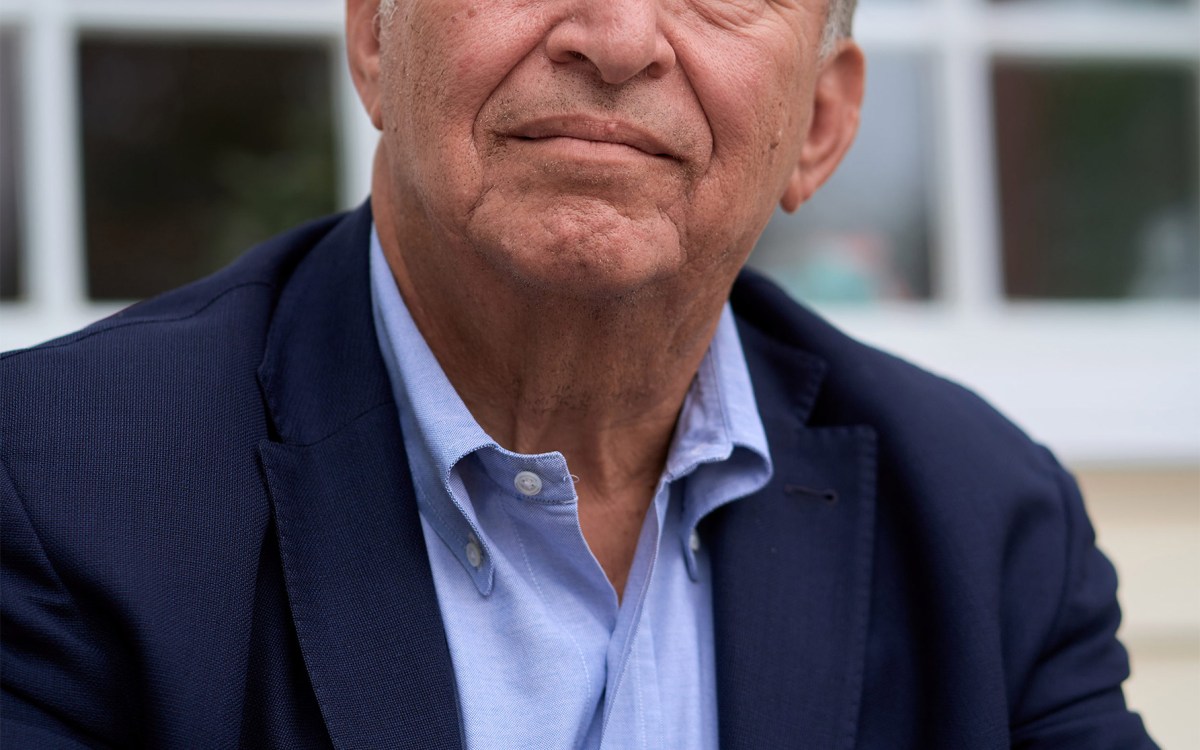

Jason Furman

GAZETTE: We’ve seen five straight weeks of declines on Wall Street with many of the biggest tech and digital media firms posting big drops in stock valuation. What’s driving this volatility?

FURMAN: One thing that runs through the entire economy is interest rates. And interest rates have gone up incredibly quickly because of what the Fed has already done and what the Fed is expected to continue to do. When interest rates go up, it becomes more attractive for investors to move their money into bonds and out of stocks and that causes stocks to fall.

If you’re going to deliver profits in the far future, you’re going to be much more sensitive to interest rates. The NASDAQ has more speculative stocks that are going to deliver earnings five or 10 years from now. And if you discount those earnings back to the present at a higher interest rate, they sort of shrink more.

Now, there’s other things going on, too. Elon Musk selling his Tesla shares to buy Twitter hasn’t helped the NASDAQ, and supply chain problems in China have hit Apple. So, there’s a lot of company-specific stories. But the most important is this one story that runs through everything and that’s interest rates.

Are we headed for a recession? Furman says that largely depends on consumers, who have kept up spending despite inflation by tapping their savings. “How long will they be able to continue doing that?”

File photo by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

GAZETTE: The Consumer Price Index released Wednesday shows inflation at 8.3 percent and the national average price per gallon of gas is at $4.40, according to AAA. What do these numbers tell us about where inflation is now or is going?

FURMAN: The inflation data is troubling because the price increases are so broad. For a while last year, you could make an excuse that, “Oh, it’s just car prices going up” or in March, “Oh, it’s just gasoline prices going up.” But now it’s the price of almost everything going up. And so, the broadening of inflation has been one concern. A second concern is that as some inflation rates slow, for example, the price increase of goods has slowed, other inflation has increased. The price of services, especially things like rent, has gone up.

If you want to ask what’s happened to living standards over the last year, the cost of living has gone up 8 percent. If you want to ask how much inflation we will have going forward, you want to take out volatile things like oil prices and gasoline prices because they’ve spiked really high, and they’re probably going to come down. We don’t want to assume that they’re going to keep increasing like they’ve increased. And so, economists often look at something called “core inflation” that tracks the volatile food and energy components. That’s running at more of a 6 percent rate instead of an 8 percent rate. It’s not as bad as the headline, but it’s unbelievably high compared to the 2 percent target the Fed has.

GAZETTE: The U.S. has decades-low unemployment and wages are up across every sector. That sounds like a good thing, but does the Fed see it that way?

FURMAN: The problem is that workers only have more power to get higher nominal wage increases. But what matters, of course, is the purchasing power of your wages. And that has been falling, not rising. So yes, workers have been getting larger nominal raises, but they haven’t been enough to keep up with inflation. At this point, the Fed would like people to be getting smaller, nominal raises because if people keep getting paid 5 percent more a year than they were getting the year before, it’s very hard to sustain that without higher inflation.

When the Fed raises interest rates, they reduce demand. Higher mortgage rates mean people buy fewer houses; higher car loan rates mean people buy fewer cars; higher borrowing rates for businesses means they invest less in power plants and equipment. All this cools off demand, reduces the number of workers people want to hire, and reduces the pay increases. The hope is it doesn’t hurt workers that much because it reduces inflation just as much as it reduces wage growth and so workers stay protected. That’s the hope, but very far from the certainty.

GAZETTE: There’s a split on whether we are heading for a recession. What factors will be most determinative in steering us clear from going there?

FURMAN: The most important is consumers. That’s 70 percent of the economy. Consumers have been seeing their inflation-adjusted pay falling, but they’ve held up their consumption by dipping into their savings. How long will they be able to continue doing that? How long will they want to continue doing that is probably the most important factor in whether the economy goes into recession this year.

I’m relatively unworried about a recession over the next year because consumer spending has continued to be very strong, and consumers have about $2.3 trillion of excess saving that they accumulated during the pandemic that could still spend out over the next couple of years.

GAZETTE: With high gas prices creating major political headwinds, President Biden said this week that lowering inflation was a top priority of his administration. He has already tapped the Strategic Petroleum Reserves. What more can he do?

FURMAN: The biggest tools are lowering the China tariffs; ending the moratorium on student loan interest payments would also help with inflation. The unemployment rate for college graduates is below 3 percent, so the economy should be in good enough shape to handle that. Beyond that, he doesn’t have a lot of tools. Inflation is primarily the responsibility of the Fed and it’s going to take time to bring down.

The most politically salient part of inflation is gasoline prices. The truth about gasoline prices is that part of inflation mostly is President Putin’s fault. And that part of inflation President Biden has helped with by releasing gasoline from the strategic petroleum reserves. The good news is that part of inflation is likely to level off or come down. We’ll probably have lower gasoline prices on Election Day than we have today. So, even if overall inflation is high, the part of inflation that people most notice should be getting better. There’s very little reason for them to keep rising the way they have. And historically, they tend to mean revert. The market is predicting that oil prices are going to come down over time if you look at futures prices.