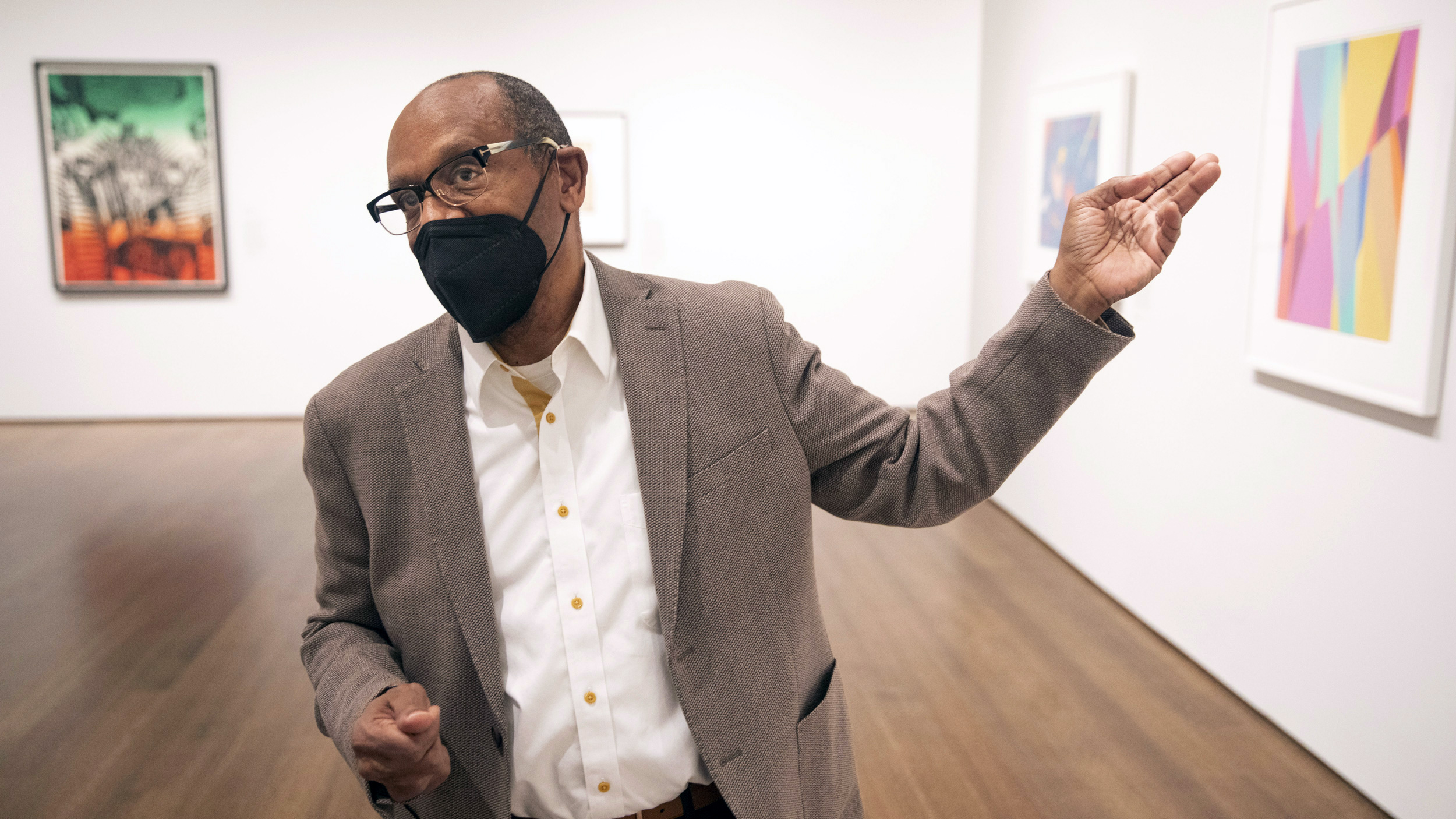

Allan Edmunds, founder of the Brandywine Workshop and Archives, recently visited the Harvard Art Museums to view the exhibition and meet with contributors who shared their personal responses to the prints on display.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Art with a conscience

Prints from the Brandywine Workshop and Archives, at the Harvard Art Museums, address social issues

A group of pioneering prints from the Philadelphia-based Brandywine Workshop and Archives now hang on the walls of the Harvard Art Museums in a new exhibition that marks the museums’ first presentation of these recently acquired works. The Brandywine provides a fertile environment for artists from diverse backgrounds to experiment with printmaking, and this year marks the 50th anniversary of its founding by artist and art educator Allan Edmunds.

Representing the output of nearly 30 artists, many of the prints on display address urgent social, political, and cultural issues. As a tribute to the engagement the workshop fosters in its communities, the museums developed their own creative community on campus that contributed to the exhibition. Members of museum staff, students, faculty, scholars in related fields, and artists shared their personal responses to the artworks via written labels on the walls of the exhibition.

“Prints from the Brandywine Workshop and Archives: Creative Communities” is open to the public and on view through July 31. Interested in sharing your viewpoint? The museums are now welcoming contributions to an online companion to the exhibition.

“Cut,” 2016, by Odili Donald Odita, is connected to the Nigerian-born artist’s 2015 mural, “Our House,” painted on the outside of the Brandywine workshop building in Philadelphia. “Like its exterior relative, this print derives power from its diagonal line — the cut, or what the artist calls ‘the coming together and coming apart,’” wrote Narayan Khandekar, senior conservation scientist and director of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard Art Museums.

“200 Yrs,” 2008, by Allan Edmunds. “This offset lithograph compresses U.S. history to commemorate Black resilience. Its title references the years between the Slave Trade Act of 1808, which banned the importation of enslaved individuals from Africa to the United States, and the 2008 election of Barack Obama, the first U.S. president broadly recognized as Black. Yet its iconography precedes 1808, including the Brookes slave ship and the written names of Crispus Attucks and Sojourner Truth,” wrote William Henry Pruitt III, Ph.D. candidate, Department of African and African American Studies, Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

“Chief Mechanic,” 2012 (left), and “Star Pilot,” 2012 (right), by Robert Pruitt. “Inspired by science fiction and comic books, the artist envisions a world in which individuals of African descent band together to herald the Mothership Defense Squadron. This narrative aligns these prints with the Afrofuturist movement, which imagines a liberated African diaspora leading a culturally and technologically advanced civilization,” wrote Sophie Lynford, Rousseau Curatorial Fellow in European Art, Harvard Art Museums.

A student studies “Hagar’s Dress,” 2007 (left), by Janet Taylor Pickett, and “Untitled (color),” 2006 (right), by Danny Alvarez. “Rooted in the Mexican print tradition, Alvarez’s work invites us into the imaginary of the ever-moving space of the ‘borderlands.’ Informed by his lived experiences as an artist from El Paso, Alvarez uses the Mexican flag’s colors as background for a story in which multiple times and spaces merge,” wrote María Luisa Parra-Velasco, senior preceptor in Romance languages and literatures, Harvard University.

“Autobiography: Past & Present II,” 2005, by Howardena Pindell. “Pindell is known for her textured paintings and mixed-media works, which can be seen as accumulations, or perhaps collections, of remembered things. They bear the traces of a lived history, a story both in and across space and time. Her works are also feats of formal ingenuity: geometry and abstraction are pushed to new possibilities, telling full, rounded narratives that refuse flattening and vacuity,” wrote Chassidy Winestock, Ph.D. candidate, Department of History of Art and Architecture, Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

“Actress,”1993, by Hughie Lee-Smith. “The silhouette [on the left] seemingly mirrors the inner emotions of the actress, who looks off to the right, caught in the private, insular moment of reading lines,” wrote Jessica Ficken, Cunningham Curatorial Assistant for the Collection, Division of Modern and Contemporary Art, Harvard Art Museums.

“#6: Roundup at Zamosc,” a lithograph from Murray Zimiles’ portfolio “Holocaust, 1987,” shows the horrors of the Nazi genocide of Jewish people and other minority groups during World War II. “The rearing horse, the fallen man at left, and the contorted expressions of the figures echo the composition of Pablo Picasso’s ‘Guernica,’ a monumental black and white painting that testifies to the devastation of the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s,” said Rachel Vogel, Ph.D. candidate, Department of History of Art and Architecture, Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

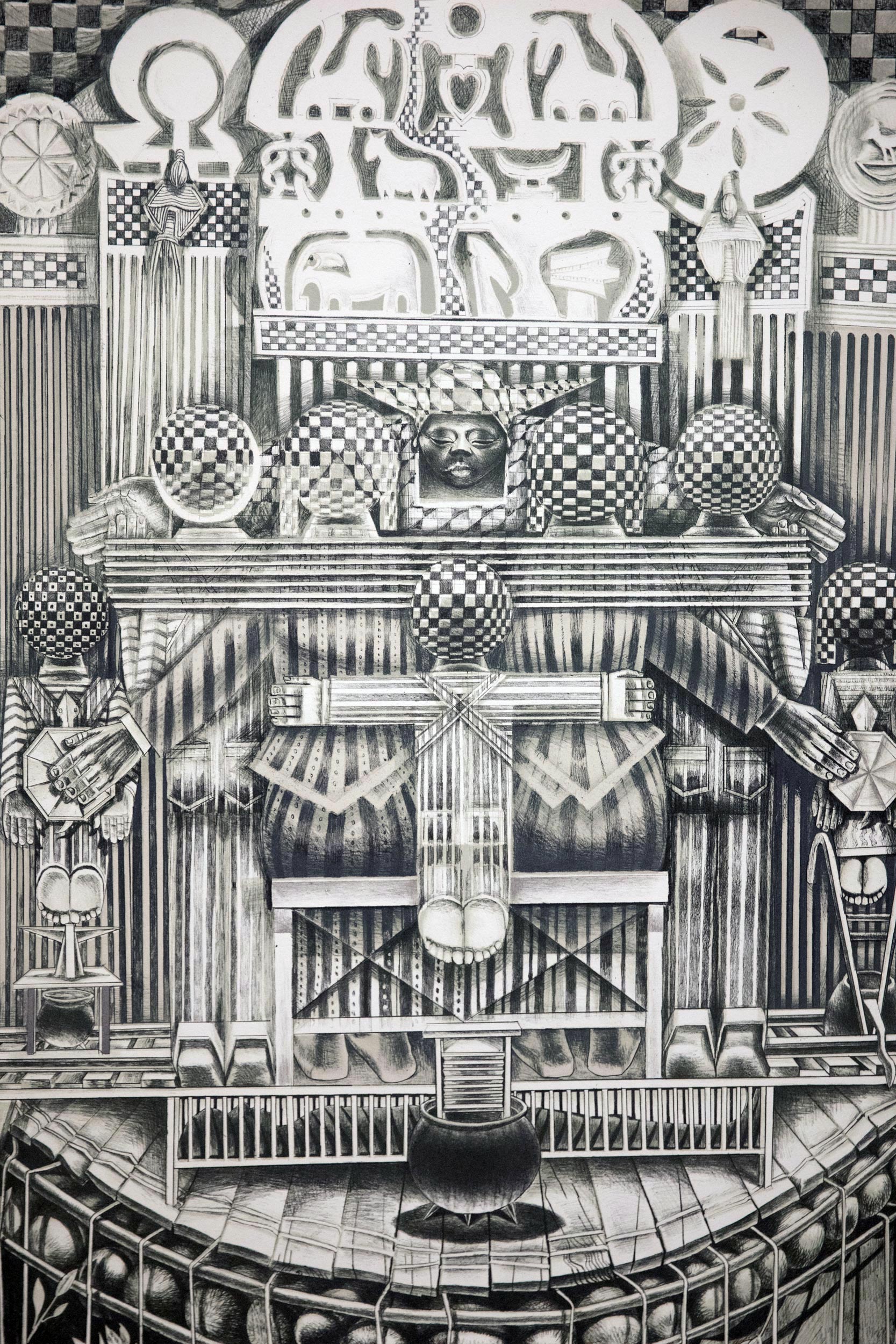

A detail view of “Family Ark (monochrome),” 1992, by John Biggers. “In this monumental print, Biggers uses a format often associated with altarpieces in Christian churches: the triptych, a three-part work of art imbued with sacred meaning. Trained as a printmaker and muralist, Biggers does not shy away from scale or complexity in this lithograph, densely layered with geometric elements, patterns, and religious symbols,” wrote Joelle Te Paske, M.Div. candidate, Harvard Divinity School.

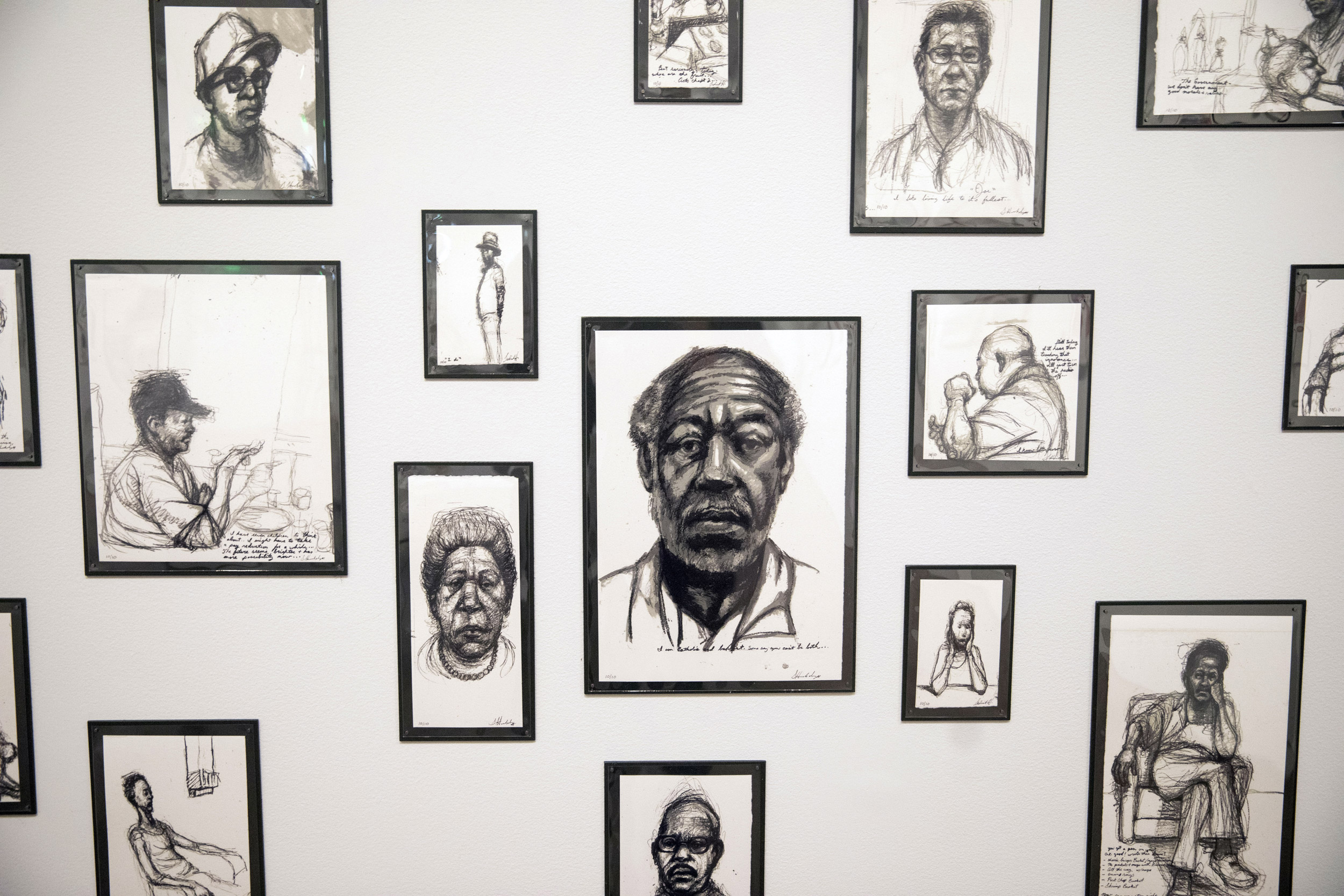

A detail view of “The 99% — Highland Hills,” 2013, by Sedrick Huckaby. “[Huckaby’s] portraits of people from his Fort Worth, Texas, community are composed with quick framing lines that resolve into a virtuosic succession of swirling loops that convey volume, cross-contour verticals, and painstaking hatch and cross-hatch patterns of varying intensity and length. The result is an intimate aggregate of persons and situations, separately attended to but conceptually in conversation with each other and the viewer,” wrote Horace D. Ballard, Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. Associate Curator of American Art, Harvard Art Museums

Co-curators of the exhibition Elizabeth Rudy (second from left) and Sarah Kianovsky (right), the curator of the collection for the museums’ Division of Modern and Contemporary Art, discussing the 101 intimate portraits that make up Sedrick Huckaby’s series “The 99% — Highland Hills,” 2013. A group of Harvard students worked on the installation in consultation with the artist.