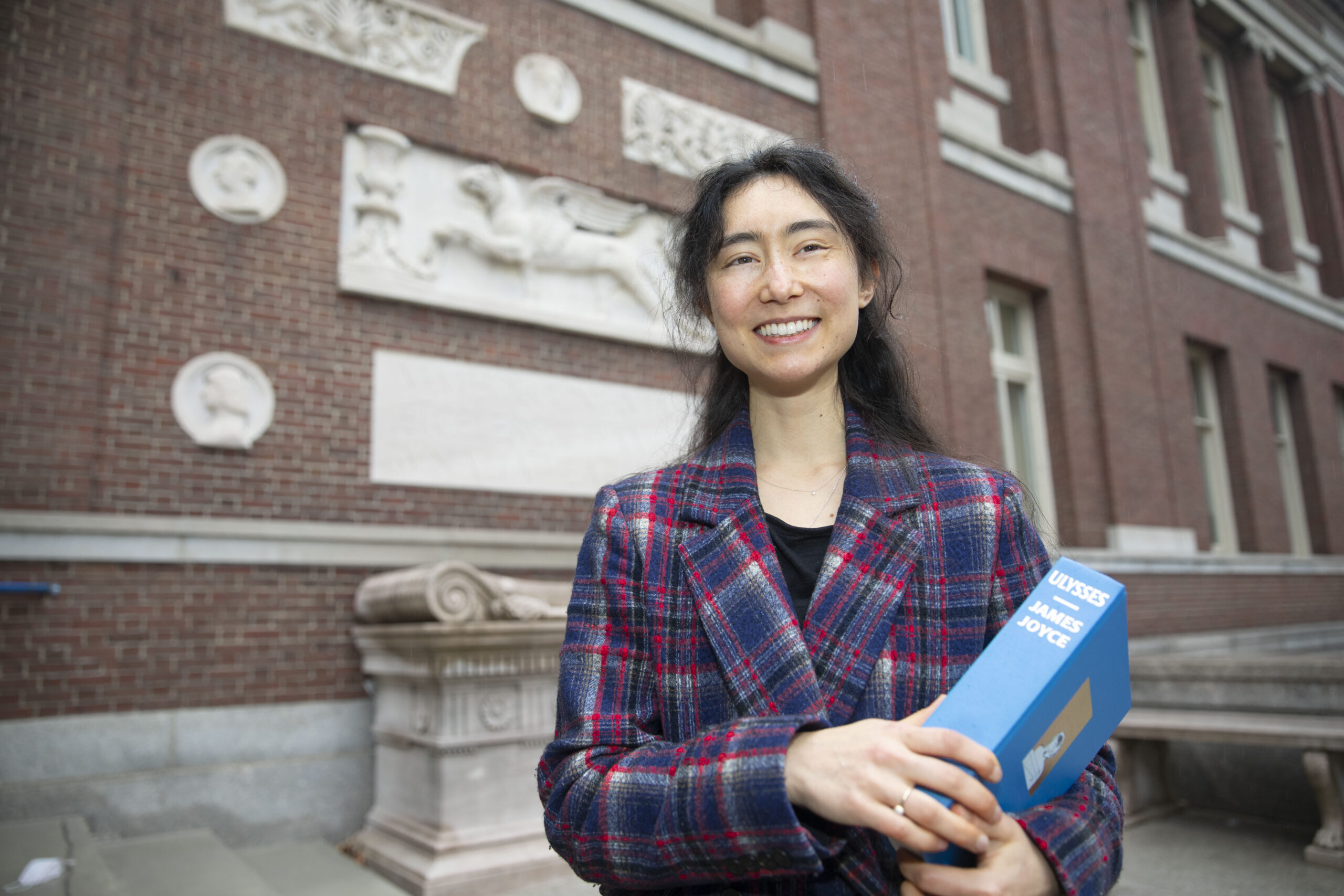

After taking a seminar on James Joyce’s Irish modernist classic, senior Sorcha Ashe said, she began to think of the book as a kind of literary friend. “I see elements of Joyce everywhere now.”

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

How to read ‘Ulysses’? With gratitude.

Students, scholars find everyday rewards on the other side of Joyce’s century-old epic

Four years ago, Sorcha Ashe ’22 enrolled in the seminar “Complexity in Works of Art: Ulysses and Hamlet” with a lofty goal: read one of the most challenging novels in the modern English canon.

“‘Ulysses’ has kind of a lore around it as being an impossibly complicated book, and I definitely thought that it was going to be beyond me when I started,” said Ashe, an integrative biology concentrator from St. Paul, Minnesota. “But I had always wanted to read it because my father is Irish and it’s his favorite book.”

Guided by instructor Philip Fisher, Felice Cowl Reid Professor of English, Ashe and her classmates journeyed together through James Joyce’s Irish modernist classic, which was first published in book form in February 1922. The rewards were equal to the task.

“I found it to be one of the most enjoyable reading experiences I’ve ever had,” Ashe said. “To get to talk about those challenging parts and the enjoyable parts with other people made the experience so much more valuable than it would have been if I had read it on my own. It was such a joy to hear different people’s takes on the same set of words.”

Ashe’s struggle and delight with the novel echo century-old refrains from Joyce’s contemporaries. Fellow modernists including Virginia Woolf and T.S. Eliot reacted with confusion and envy to the author’s combination of rich prose, shifting perspectives, and Homeric allusions in a meandering interior story that spans but a single day.

“Virginia Woolf was quite defensive about ‘Ulysses’ when it came out, because she said it was boring and overrated,” said Beth Blum, an assistant professor of English and Joyce scholar. “But after sitting with it more, she saw what he was trying to do and appreciated it. She began to see that Joyce was, as she put it, trying to get thinking into literature.”

Eliot lamented: “It is a book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape.”

“Joyce’s sentences can become companions in your life,” says Assistant Professor of English Beth Blum. “They pop up in useful moments, and have an uncanny ability to get lodged in your brain.”

Harvard file photo

The book’s hold on literary culture is matched by few others, Blum noted. Internet searches yield multiple “how-to” guides for reading the novel, numerous essays debating whether one should even try, and arguments about which version should be read — with or without typos. All of these elements have coalesced into mythology, said Blum.

“Reading a book like ‘Ulysses’ represents a form of cultural capital and education, but the novel is also associated with a more democratic experience of humanity through the common man, Leopold Bloom,” she said, referencing Joyce’s protagonist. “Approaching the novel as a personal challenge allows you to reckon with difficulty and learn to persevere in the face of ambiguity and uncertainty. I think that is part of the reason why it continues to appeal to people and endures.”

Reflecting on her College experience with “Ulysses,” Ashe said the novel altered her trajectory in ways she never would have predicted. Her first-year adviser, George Putnam Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology David A. Haig, gave her his copy of the novel, which she treasures. As a junior, she enrolled in Blum’s “Extreme Reading: The James Joyce Challenge.” These classes and others nurtured a love of prose that led her to pursue a graduate degree in Irish modernist literature, though she remains committed to medical school and a career as a doctor.

“I see elements of Joyce everywhere now,” she said. “Sometimes I’ll be walking around a city and thinking about what Bloom would notice, or how Joyce would have enjoyed the walk.”

She also began to think of the book as a kind of literary friend.

“‘Ulysses’ is a language-driven book and there was comfort in knowing that you could put the book down, take a walk, and think about what you read before returning to grapple with a passage,” said the Kirkland House resident. “That helped me form a relationship with it.”

Ashe is far from alone, said Blum, noting that readers have looked to “Ulysses” as a companion during life transitions and moments of uncertainty since its publication. In her 2020 book, “The Self-Help Compulsion: Searching for Advice in Modern Literature,” she examined early advertisements from the novel and found that it was often marketed for readers looking to learn about life.

“The idea was that there’s really no better book to read to understand the challenges of parenting, of marriage, of trying to be an artist or a writer, of struggling against your family and trying to go out on your own, than ‘Ulysses,’” said Blum.

Even today, she added, “Joyce’s sentences can become companions in your life. They pop up in useful moments, and have an uncanny ability to get lodged in your brain. They become resources that you can turn to in moments of stress or grief.”

She encourages would-be readers to embrace the confusion that comes with diving into the work. It’s a difficult task in a culture based on speed of information and opinion — but not impossible, said Blum.

“It’s a book that inherently rewards second readings and third readings. When we give a text that kind of attention, it opens up just as many worlds and threads.”