Toni Morrison was featured at former University President Drew Faust’s inauguration. The Nobel Prize-winning novelist gave a reading during the event in 2007.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Enduring memories of Toni Morrison

Divinity School’s Davíd Carrasco shared stories from his 32-year friendship with late Nobel laureate

The first lesson Harvard Divinity School’s Davíd Carrasco learned from the late novelist Toni Morrison involved the power of reading and the written word. Morrison said she saw herself as a “reader who wrote.” She learned to read at the age of 3 and worked as a cataloger at a library in her hometown of Lorain, Ohio, as a teenager.

Later, as book editor at Random House, she played a major role in bringing Black writers and literature to print, with a focus on Black culture, history, and “the artistic strategies the works employed to negotiate the world they inhabit,” Carrasco said. Morrison’s constant reading greatly informed her writing. “She was never a static author,” he said.

On the eve of what would have been Morrison’s 91st birthday, Carrasco shared stories from his 32-year friendship with the Nobel laureate. The Thursday evening remote lecture was hosted by the Harvard Extension Alumni Association Midwest Chapter.

Carrasco, the Neil L. Rudenstine Professor of the Study of Latin America, said the two met in 1990 when he attended a lecture by Morrison about the Herman Melville novel “Moby-Dick.” The lecture analyzed how people of color were portrayed negatively in the novel and the effect this had on not only readers, but on other writers.

“[As she spoke,] I felt a stirring of memories, growing up as a Mexican American,” Carrasco said. “A tissue of profound meaning was growing between me and Morrison.”

He approached her after the talk and the two shared their love for the book “The Words to Say It” by Marie Cardinal, on which Morrison had based her Massey lecture series, “Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination.” They became fast friends, a connection that would last until her death in 2019.

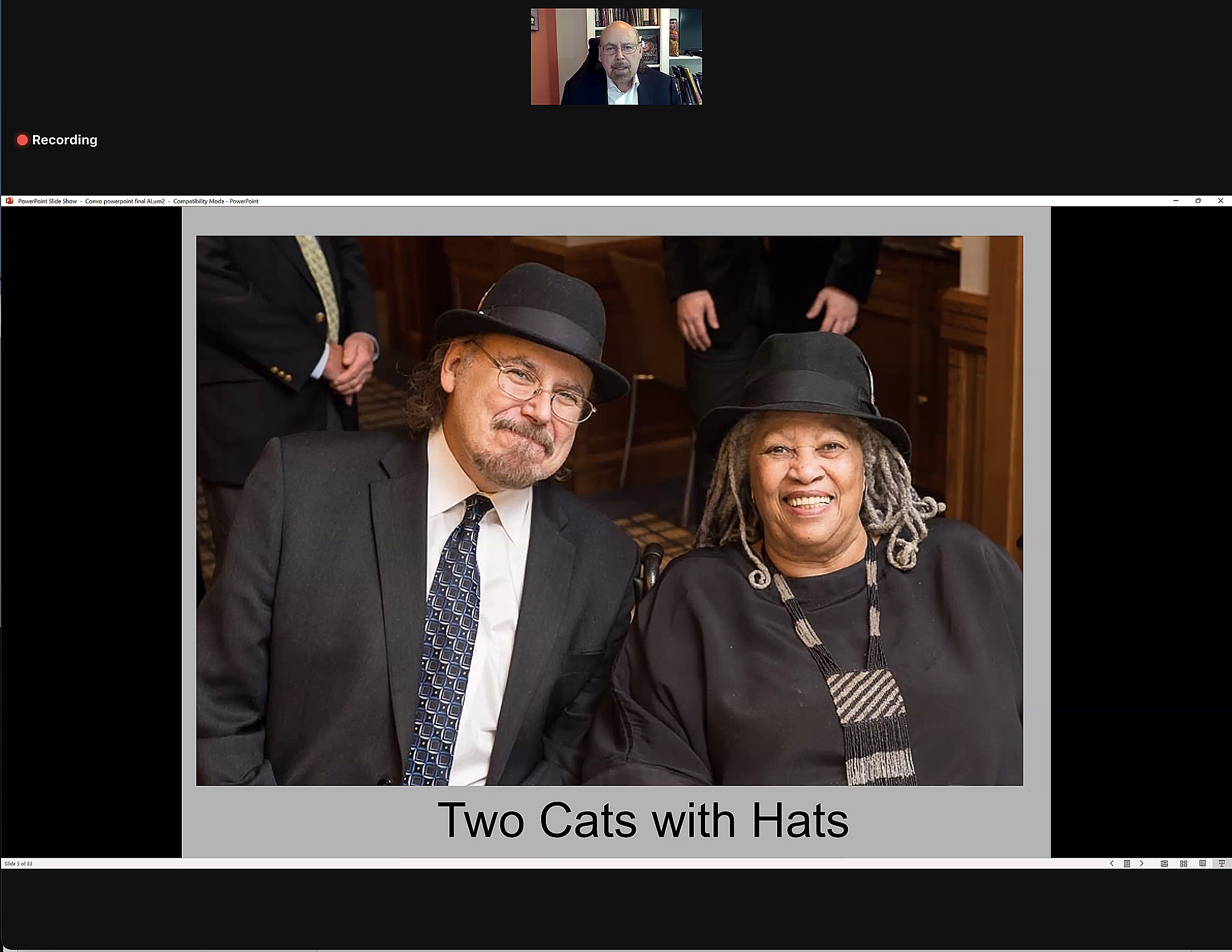

Davíd Carrasco shared a photo of himself and Toni Morrison during the presentation.

Carrasco said that besides the importance of reading Morrison imparted four other invaluable lessons to him.

The second lesson, he said, was that “racism is a cosmology with a practice.” Morrison’s writing explored not only surface-level racist beliefs and attitudes, but its deeper effects on humanity. This exploration is prominent in her novel “The Bluest Eye,” in which a young Black girl, a social outcast who sees herself as ugly, wishes above all else to have blue eyes like her idol Shirley Temple.

Growing up in Washington, D.C., people often told Carrasco and his family to “go back to where he came from,” which was very alienating to the young boy.

“Morrison showed how white supremacy can permeate every facet of reality,” he said. “We in academia sometimes settle with the idea that racism is a social construction that can be deconstructed. … [But] we who suffer racism undergo it as a total aggression.”

The third lesson came during Morrison’s trip with Carrasco to Mexico City in 1995. Through novelist Carlos Fuentes, Carrasco arranged a dinner party with Gabriel García Márquez. It was there that Carrasco learned that Morrison’s imagination was open to crossing borders.

“I couldn’t really eat,” he recalled. “I said, ‘I’m in a world of magical realism.’ It was an incredible night.”

Toni Morrison (center) at Gabriel García Márquez’s (third from left) home in Mexico City.

Photo by Fabrizio León Díez

Despite the language barrier, Márquez and Morrison spoke of their shared passion for literature, as well as for each other’s work.

“She drew inspiration and content from reading a Latin American writer with another cosmology,” said Carrasco. “A bridge opened between them that lasted until he passed away [in 2014].”

Morrison’s lasting legacy comes from the fourth lesson: Her literary inspiration always came from a place of joy and responsibility to Black women, he said.

In 1993, Morrison became the first Black woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Her selection sparked criticism by some who felt that her focus on Black life (particularly the lives of women) was too narrow. But, Carrasco said, she never wavered.

He noted that Morrison once said, “My inspiration is not born out of protest, but out of pure joy.”

“She’s not just reacting. If you just react, you let the critic set the agenda,” Carrasco said. “She’s saying, ‘I set my own agenda.’”

In his presentation, Carrasco recalled a quote from a 1990 interview in which Morrison referenced the character Pilate from her book “Song of Solomon.” She drew a direct correlation to women she knew in real life.

“In body, she’s gone, but in spirit, I think she’s growing in many ways.”

David Carrasco

“’They were just absolutely clear, and absolutely reliable. They had a blessedness. But they seemed not to be fearful,’ she said. ‘It’s to those women that I really feel an enormous responsibility. I think about my great-grandmother, and her daughter, and her daughter. They never knew from one day to the next about anything. But they believed in their dignity, that they were people of value, that they had to pass that on.’”

The final lesson Carrasco learned from his friend was to have goodness and mercy in what you do.

In 2012, Morrison delivered the annual Ingersoll Lecture on Immortality at HDS. Prior to the lecture, the School organized a six-week seminar studying her work. She was invited to spend an afternoon with the group.

“She wanted to be with these students because she spent so many years of her career and life with students,” Carrasco said.

Morrison carried this spirit of generosity, warmth, and curiosity through her writing. Carrasco shared a quote on this attitude from a 2019 article she wrote for The New York Times.

“‘Expressions of goodness are never trivial or incidental in my writing,’” she wrote. “‘Allowing goodness its own speech does not annihilate evil, but it does allow me to signify my own understanding of goodness: the acquisition of self-knowledge.’”

For Carrasco, these five memories — and the lessons learned from them — will live on.

“In body, she’s gone, but in spirit, I think she’s growing in many ways,” he said.