The MIT-Harvard project explores ways to ease the effects of the coming energy transition in parts of the U.S. that depend on fossil fuel-related industries, such as the oil-rich Gulf Coast.

iStock by Getty Images

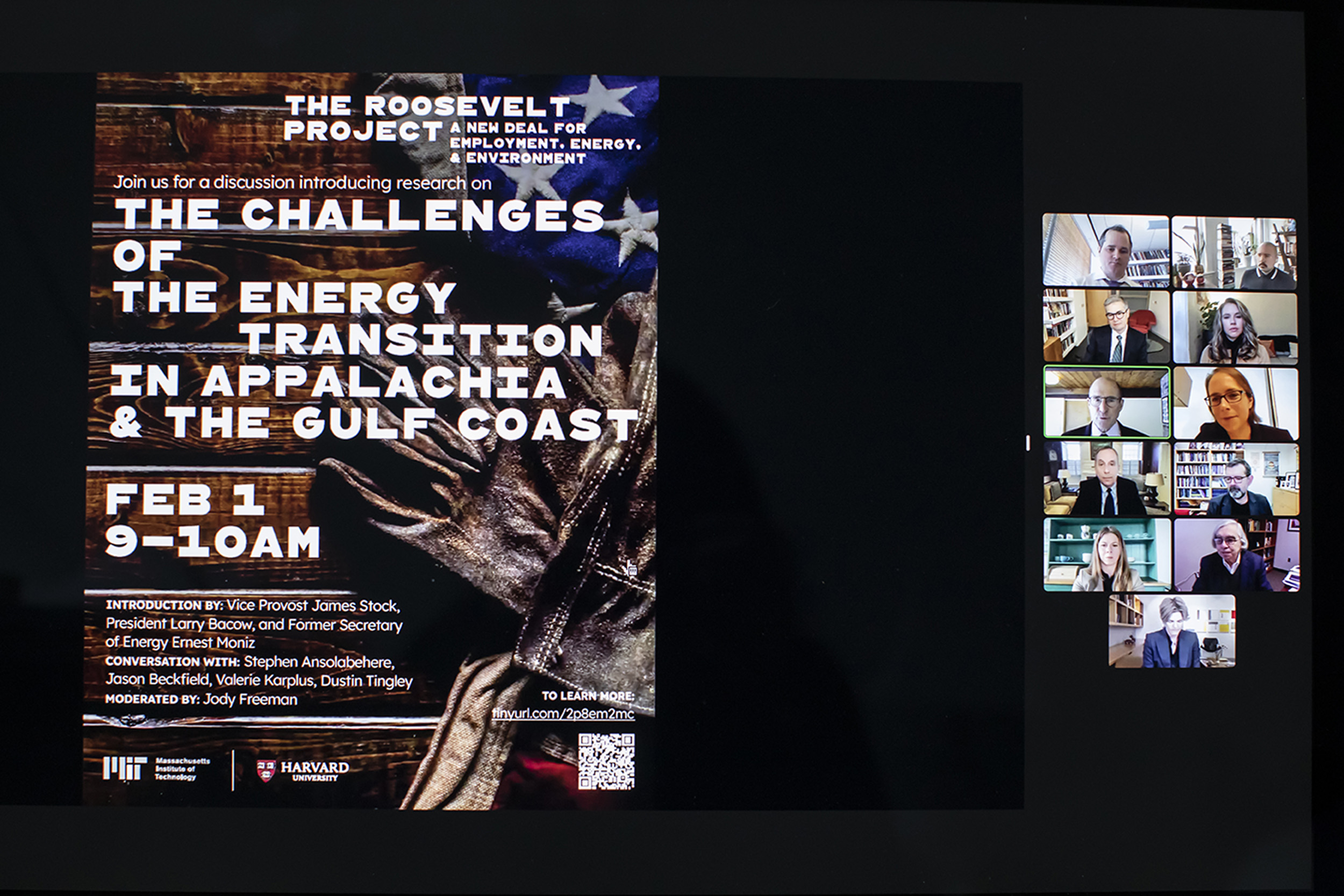

Biggest hurdle to U.S. energy policy revamp? Millions of displaced workers

Harvard-MIT Roosevelt Project points to studies of Gulf Coast, Appalachia, ways to ease transition

Fill in the blank: Coal/oil/natural gas is king.

The saying reflects the economic and employment reality in the oil-rich U.S. Gulf Coast, the coal towns of Appalachia (whose latest hopes are pinned to less-polluting but still problematic natural gas), and the automotive industrial complex of car makers and parts suppliers across the Midwest. It also represents the biggest hurdle to a national consensus on a needed shift in climate change policy.

“If you’re living today where automobiles or energy and steel were — or are — king, you’re probably and rightfully anxious,” said Harvard President Larry Bacow, who grew up in Pontiac, Michigan, and has family members who eye the coming energy transition with anxiety and skepticism. “They fear what it will mean for their town, their region, and their livelihoods. These people are not, in fact, being irrational. They are looking out for their own self-interest — clearly in the short term. They believe, and in many cases have good reason to believe, that they could emerge as net losers.”

Bacow was an introductory speaker at a webinar this week by The Roosevelt Project, a Harvard and MIT collaboration started by MIT professor and former U.S. Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz. The initiative seeks ways to ease the coming transition to clean energy by focusing on places that will feel it most sharply. Moniz said at the Tuesday event that there are significant political repercussions to the economic concerns of the millions whose lives will undeniably be disrupted.

“If we do leave workers and communities behind, as we are seeing today in Washington, D.C., we will just continue with political headwinds,” Moniz said.

The project has sponsored white papers on the problem and produced four in-depth case studies of regions where the dislocation may be felt most: the industrial Midwest; New Mexico, which has a significant fossil fuel industry; the oil-rich Gulf Coast; and Appalachia, already hit hard by the decline in coal even as jobs in natural gas extraction increase.

Harvard President Larry Bacow discusses The Roosevelt Project and its vision for a future of renewable fuel.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Tuesday morning’s event focused on two cases: southwest Pennsylvania and the Gulf Coast. For each, teams of students, local partners, and faculty members fanned out and interviewed residents, community and industry leaders, workers, heads of community groups and vocational initiatives. Jason Beckfield, the Robert G. Stone Jr. Professor of Sociology at Harvard, said the effort revealed that one barrier to understanding is a history of exclusion, mistrust, and disrespect among groups on all sides. It was a big enough factor, he said, that the teams drew up a list of “trigger words” that had the potential to halt conversation, an exercise that deepened understanding of adversarial positions and sparked ideas for ways to keep talking.

“There’s a very strongly felt disrespect that makes it hard for people to sit at the table together,” Beckfield said.

There are opportunities in several areas, Beckfield said, including seeking natural solutions to storm vulnerability and pollution and easing the mismatch between worker skills and the new jobs being created through a Gulf Coast Skills Consortium. To keep people talking, the team suggested creating a Gulf Energy Transitions Council with wide representation, along with a Just Transition Internship Program to cast the net even wider for underrepresented groups.

In Pennsylvania, a workforce battered by coal’s decline has turned to natural gas now available through fracking technology. According to Stephen Ansolabehere, Harvard’s Frank G. Thomson Professor of Government, opportunities to transition to the new energy economy exist in new jobs in carbon capture and sequestration and in the use of hydrogen as a fuel. Clean energy manufacturing is another potential area of growth, with the potential to manufacture low-carbon steel, windmills, and solar panels. The region also is one of the most dependent on nuclear power in the U.S., so there may be opportunities presented by a new generation of more efficient, safer reactors. Environmental remediation is another potential jobs generator, as there are 400,000 abandoned gas wells in need of decommissioning.

Elizabeth Thom, a doctoral student who worked on Ansolabehere’s team, said that another Pennsylvania strength is that there are hundreds of groups and organizations that can lend a hand planning and executing the transition. But, she cautioned, the time to start is now, since efforts have to be coordinated among many players, and it takes time to foster job growth and retrain workers, even in a region that has already shifted from steel production to coal to natural gas, and where “reinvention is in its pedigree.”

Dustin Tingley, professor of government and deputy vice provost for advances in learning at Harvard, said one of the pleasant surprises was the extent to which environmental remediation jobs can potentially fit existing skillsets. One of the biggest challenges, Tingley said, will be to ensure that policies, resources, programs, and jobs are not only available, but available at the right time, particularly for people who can’t go long periods between paychecks.

“You have to get the timing right,” Tingley said. “You can’t say to people, ‘You have to transition now,’ and have nothing on offer.”