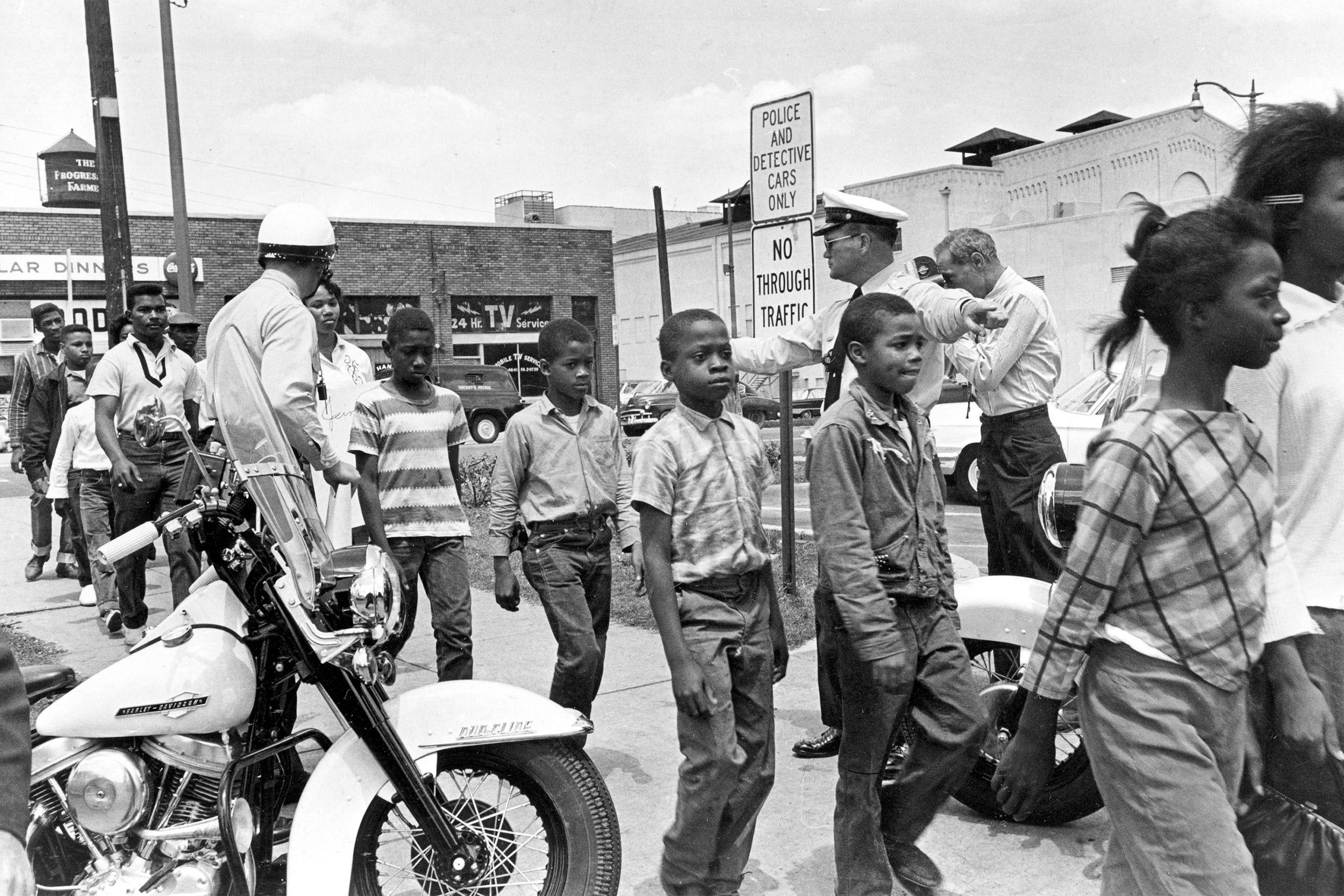

On May 4, 1963, hundreds of children were led to jail following their arrest for protesting against racial discrimination near city hall in Birmingham, Alabama.

AP File Photo/Bill Hudson

Rescuing MLK and his Children’s Crusade

Tomiko Brown-Nagin’s book traces tactics of groundbreaking lawyer Constance Baker Motley amid pivotal protests

Excerpted from “Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality” by Tomiko Brown-Nagin, Dean, Harvard Radcliffe Institute, Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law, and Professor of History.

In the spring of 1963, the eyes of the nation turned to Birmingham, Alabama, then known as the home of a thriving iron and steel industry. In April and May of that year, Birmingham, a land trapped in a “Rip Van Winkle” slumber on issues of race, and the nation’s “chief symbol of racial intolerance,” according to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., became a flashpoint in the Black struggle for equality.

In his inaugural address, George C. Wallace, elected governor of Alabama in 1962 on a pro-segregation and states’ rights platform, rebuked the civil rights movement. “I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny,” the governor said. He vowed to maintain “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor, Birmingham commissioner of public safety and an unapologetic racist who controlled the police and fire departments, also vowed to defend white supremacy. The civil rights movement had encountered two of its fiercest foes.

For five weeks, beginning April 3, 1963, King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and a coalition of grassroots activists led by Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR), a “firebrand” known for his invincible courage and confrontational leadership style, staged a mass civil disobedience campaign and squared off against the ardent segregationists. Through sit-ins, demonstrations, and boycotts, protesters sought to expose the cruelty of Jim Crow and draw attention to the value of Black purchasing power; ultimately, they hoped to desegregate the city and increase Black employment opportunities.

The campaign was the brainchild of Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker of SCLC, who called it “Project C.” The “C” stood for “confrontation”— nonviolent confrontation. “If we could crack Jim Crow in Birmingham, known as the nation’s most segregated city,” Walker said, “then we could crack any city.” Shuttlesworth, who had been brutalized and nearly blown to bits in retaliation for his efforts to desegregate Alabama’s schools and buses, agreed that a successful drive against Jim Crow in Birmingham would reinvigorate the movement. He warned that the campaign would be extremely dangerous, but could be extremely rewarding: “You have to be prepared to die before you can live in freedom,” he said.

In its early days, the meticulously planned campaign had generated little community support; many middle-class Blacks actively opposed it, and casual observers largely ignored it. “[O]ur community was divided,” King conceded. Small numbers of activists — a mere seven at a local cafeteria and eight at Woolworth’s — turned out to stage sit-ins on April 3. Instead of contending with the demonstrators, workers took the day off. Only a smattering of the protesters were arrested. Even Shuttlesworth generated little enthusiasm when he led a sit-in on April 6; only a few dozen people came to join him.

The very next day, on April 7, there was another small demonstration involving about 20 people, an embarrassingly small number, but this time it ended differently. Connor unleashed police dogs and firehoses on the peaceful and prayerful protesters marching toward the town center. In the chaos, several dogs pinned a 19-year-old Black man to the ground, and officers kicked the man — a bystander uninvolved in the movement — as he lay there helpless. News reports and public attention highlighted this incident of police brutality. The spectacle grabbed the attention of those who previously had ignored the protest, and SCLC found the “key” to motivating the Black community and garnering press coverage: demonstrations that precipitated violent confrontations with Connor’s police.

A few days later, on April 10, King, Shuttlesworth and the other ministers leading Project C defied a court order, which had been a part of city officials’ plan to halt the movement. First, officials refused to issue the protesters a permit to parade; next, they secured a court order enjoining unlicensed protests. King called the injunction nothing more than a “pseudo-legal way of breaking the back of legitimate moral protest.”

King and his movement had come to a crossroads. Out of respect for the U.S. Supreme Court’s stand against segregation in Brown v. Board of Education and other federal court decisions that aided the movement, King had vowed never to violate a federal court order. At the same time, the ministers concluded that the movement owed no deference or loyalty to state and local courts, where, more often than not, proud racists presided.

In the face of the command to stop engaging in civil disobedience without a permit, King held a press conference. “Injunction or no injunction,” he said, “we are going to march tomorrow. I am prepared to go to jail and stay as long as necessary.” Unlike federal courts, “recalcitrant forces in the Deep South,” King said in his statement, deployed the law “to perpetuate the unjust and illegal system of racial separation.” In light of the corruption of the judicial system, SCLC would go on with Project C, “out of great love for the Constitution notwithstanding the court’s demand.”

Constance Baker Motley first met Martin Luther King Jr. (left) in July 1962, after successfully arguing that protesters had the right to demonstrate in Albany, Georgia. Civil rights attorney William Kunstler is at right.

Credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, NYWT&S Collection, LC-USZ62-138785

Project C had made a radical move. It was justified, King insisted, because the court’s order was “unjust, undemocratic, and unconstitutional.” “I’ve got to march,” King said, and “if we obey it, then we are out of business,” he explained to naysayers who tried to dissuade him from violating the order.

On Good Friday, King, Shuttlesworth, and Ralph Abernathy of SCLC set out to march. The ministers led a group of about 50 from the Zion Hill Baptist Church toward town. Hundreds of spectators lined the street to witness the procession. Connor and his police force came out to meet them, standing in the middle of the street to block their way and barking orders: “Don’t let them go any further!” Connor ordered King and Abernathy arrested, while the crowd of protesters jeered.

Pushed and prodded by the officers, the protesters sang freedom songs. Meanwhile, at the Birmingham city jail, officers booked King and Abernathy and threw each in solitary confinement. Held incommunicado and alone, King worried about the fate of the movement, feeling demoralized and afraid in the “utter darkness” and “brutality” of the dungeon that confined him. The experience was no less than “holy hell,” Abernathy later said.

The protests continued, and in the days following King’s solitary confinement, friends called on President John F. Kennedy to end the “reign of terror” in Birmingham. In his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” King eloquently defended civil disobedience, countering criticism by white clergymen who called Project C “unwise and untimely.” His letter rejected the pleas to end demonstrations in the city. “I am in Birmingham,” King wrote, because “injustice is here.” The minister proclaimed that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” The letter would become the movement’s most celebrated manifesto and a vital part of the 20th-century American literary canon.

Motley watched the events in Birmingham unfold with pride and awe. Unlike her mentor at the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Thurgood Marshall, who had a frosty relationship with King and was skeptical about whether street protests were an effective means of securing civil rights, Motley saw the value of the demonstrations. Although she frequently cited the “spectacular” civil rights cases in which she played a role as the “single most important factor” in social change, she deeply appreciated the courage and the hunger for equality that motivated King and his followers. Thus when King — a man she called an “American hero” — called for her in May 1963, she did not hesitate to answer or support the Birmingham campaign.

Motley had been fighting for change in the state of Alabama since 1955. In Brown’s wake, she had traveled to that “scary place” to aid in a case that sought to desegregate the University of Alabama. That effort ended in failure when, following a riot, the university expelled Motley’s client. Years later, the battle to desegregate the state’s flagship institution of higher education continued, and Motley remained a part of it. She also represented students fighting for admission to public schools in Birmingham, Mobile, and Huntsville. At the same time, she litigated the 1963 case that desegregated South Carolina’s Clemson University. The many other assignments notwithstanding, Motley brought lawsuits to assert the constitutional rights of the Birmingham activists to protest segregation. Her efforts were vital to the movement’s continued momentum.

Following the fateful Good Friday protests in April 1963, Motley and three other lawyers were called upon to assist King. Released from the Birmingham jail on April 20, King was in legal jeopardy, facing a trial for contempt of court because of his decision to defy the order enjoining protests. Motley and LDF colleague Jack Greenberg, together with two local Black lawyers, Arthur Shores and Ozell Billingsley, defended King and Shuttlesworth, Walker, Abernathy, Andrew Young, and other leaders of SCLC named in the injunction. Along with King and his team of activists at the Black-owned Gaston Motel — headquarters of the Birmingham movement — Motley and her co-counsel strategized about how to fight the corrupt judicial system.

In room 30 of the Gaston Motel, which sat in the heart of Birmingham’s Black ghetto, Motley observed how the weight of leadership wore on King. Up close she could see King’s complexities and humanity, just as she had observed the full personhood — warts and all — of Marshall while working at his side. Strong and steady in public appearances, in private King was often mired in doubt and indecision. He frequently felt low in spirit and “alone,” even in a crowded room. Motley also experienced the lively social life that bound civil rights activists together; amid the tribulations, the freedom fighters bonded and shared a sense of community.

In late April 1963, walking alongside King, Shuttlesworth, Walker, Abernathy, Young, and other prominent ministers, Motley made her way to the courthouse, the sole woman leader in a pack of alpha males. The dignified lawyer entered the Jefferson County Courthouse and stood tall.

The courtroom teemed with spectators. Like so many others across the South, Black Alabamians had come to see the woman lawyer confirm the reputation that preceded her: when “Constance Baker Motley walked into the court, she was superb, and she took no prisoners,” according to an observer. Courthouse employees — white women — also “deserted their desks” and piled into the court to witness the famous woman lawyer. Motley’s presence and her command of the room represented something rare and different: a woman in a male environment, exerting intellectual authority and challenging sex-role stereotypes. In the Deep South of 1963, some years before the advent of the women’s liberation movement, Motley symbolized women’s emancipation. When her turn came to speak, Motley enunciated every syllable and spoke in her low and steady voice. The judge assigned to hear the case did not give her much hope for victory. She was arguing before Judge W.A. Jenkins — the very same judge who had entered the vaguely worded injunction against the demonstration to begin with. “There is not a shred of evidence,” Motley informed the judge, “that these defendants engaged in unlawful activity of any kind.” Peaceful protesters, King and his allies had made every effort to comply with the law, but had been thwarted by the city.

Connor slipped into the courtroom while Motley spoke. King’s lawyers had called the volatile man as a witness. The personification of white resistance, Connor could answer critical questions about the circumstances leading up to the Good Friday conflict. As he sat waiting his turn on the witness stand, in a dramatic display of disdain for Motley, the public safety commissioner closed his eyes. Rather than acknowledge Motley and her presentation, he pretended to sleep. By now accustomed to such juvenile displays of intolerance, Motley ignored Connor and his slight. His childish antics only strengthened her resolve. She called him to the stand.

Motley lobbed questions at Connor about his machinations in the run-up to the demonstrations. She observed that, as a known antagonist of the civil rights movement, Connor had personally ensured the movement’s fate when he and the police chief had refused to respond to Project C’s requests for a parade permit.

When Jenkins abruptly cut short her questioning, she pursued a different path. She called Lola Hendricks, a participant in the Birmingham movement, to the stand. The witness testified that Connor had been personally involved in the decision to deny a permit to Project C. In fact, Connor had scoffed at the request. “No, you’ll not get a permit in Birmingham,” he had told Hendricks. Instead, he said, he would see the demonstrators in the city jail.

A third witness lent credence to the narrative that Motley sought to develop. Under her questioning, W.J. Haley, chief inspector for the Birmingham Police Department, conceded that the city had targeted movement leaders for punishment on specious grounds. The mass arrests of Project C participants constituted the “first time in 20 years” the city had enforced the law against parading without a permit. Motley insisted on King’s innocence. Because the leaders of Project C had duly sought a permit and could not force the city to issue one, the ministers could not lawfully or logically be held in contempt of court. In a different courtroom, presided over by a fair judge, Motley’s legal strategy would have held sway. In Jenkins’s court, the logic and facts adduced utterly failed to persuade. Jenkins was interested only in the question of whether the injunction had been violated, not whether it complied with the Constitution.

Tomiko Brown-Nagin traces Martin Luther King’s desperation and the savvy legal tactics of Constance Baker Motley in “Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality.”

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Following the conclusion of the three-day trial, the judge found each of the named leaders guilty. The ministers’ actions constituted “obvious acts of contempt” and “deliberate and blatant denials of the authority of this court and its order,” Jenkins ruled. In addition to violating the order, he maintained, the accused had “used” their positions as ministers “to encourage and incite others” to do so. The judge imposed a $50 fine on each minister for criminal contempt of court and sentenced each to five days in jail. The defense attorneys immediately appealed Jenkins’s decision, postponing the jail sentences.

While the appeal went forward, King, Abernathy, and other Project C leaders regrouped to continue the battle against segregation in Birmingham. “We will march again, again, and again as long as we are denied our constitutional rights,” King promised.

***

The appeal failed, and despite King’s brilliant rhetorical defense of mass civil disobedience in his letter, the movement sputtered while he and its leaders sat in jail, and it continued to lag even after the ministers’ release. Not even King could draw the volunteers — the “troops” — needed to sustain the protests or gain major national attention. The press lost interest, and volunteers were dwindling. Defeat loomed. Some of King’s advisers began whispering that he should resign himself to the loss and quietly leave the city.

Others, however, suggested that if they lacked protesters, Project C should recruit school-aged children. While youth activists had participated in sit-ins and demonstrations, SCLC had never recruited children en masse. King expressed deep skepticism about the idea; the Birmingham city jail was “no place for children.” Others inside and outside of SCLC and ACMHR agreed, and when Birmingham’s Black middle-class leaders caught wind of the idea, they angrily rejected it. How, they asked, could any respectable person approve of the idea of serving up little Black boys and girls to Bull Connor?

But the movement’s impending collapse eventually compelled King and others to relent. Movement veterans Walker, Young, Rev. James Bevel, and Dorothy Cotton quickly got to work. Focusing on area high school students, they set out to conscript prom queens and kings, athletes, academic standouts, and other school leaders to join Project C’s marches. The recruiters distributed leaflets about the movement’s goals, and encouraged participation over the objections of parents, principals, and other administrators. Students enthusiastically joined.

Thousands of them — some elementary-school-aged — skipped class on Thursday, May 2, and gathered at the 16th Street Baptist Church. After talking and mingling with classmates, the students listened to Bevel’s exhortations and instructions. A charismatic speaker, he urged the youngsters to take a stand for freedom.

Then, just after noon that day, at Bevel’s urging, throngs of students spilled out from the imposing red-brick church across from Kelly Ingram Park and into the street. With picket signs in hand, the students marched the eight blocks toward city hall and the business district, all the while singing freedom songs. The lyrics to “We Shall Overcome,” “Oh Freedom,” and other hymns tamped down their fear and inspired feelings of joy and calm, remembered Audrey Faye Hendricks, one of the participants — only nine years old at the time. “We shall overcome / We shall overcome / We shall overcome some day / Oh, deep in my heart / I do believe / We shall overcome some day,” they sang, arms locked together. When the students reached town, happy and excited, they approached select merchants and municipal buildings.

Before long the inevitable occurred: the children’s march encountered Connor, together with police officers and firefighters. Although flustered by the presence of so many children Connor ordered his men to arrest and confine the students. Officers carted dozens to squad cars. After the cars filled, Connor called for police wagons. Then he called for school buses to transport the children to jails as more arrived on the scene. Hundreds of children were arrested that day. While held, the youths endured questioning about the mass movement. After police took Hendricks to Juvenile Hall, five or six white men surrounded the third-grader and queried her about the mass meetings and, in particular, whether leaders had forced her and others to participate. Nervous and afraid that “they might kill” her, Hendricks revealed all that a nine-year-old could about the movement’s tactics. For seven long days, the little girl remained in jail, deprived of contact with her parents. The children slept on mattresses piled on the floor, and survived on peanut butter sandwiches and milk. Larry Russell, then 16, remembered that officers fingerprinted him and treated all of the young people “like common criminals.”

News of the youths’ activism and their arrests garnered national attention and widespread condemnation. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy called what became known as the Children’s Crusade “a dangerous business” that risked innocent life. But the federal government had “no authority,” he insisted, to intervene in the local battle. So despite the criticism, youth-led demonstrations continued in the coming days.

In the face of new protests, Connor escalated his response, ordering firemen and police officers to violently suppress the demonstrations of children. Chaos ensued. As video cameras rolled and photographers snapped pictures, the Birmingham Fire Department pummeled children with high-pressure hoses as Connor yelled, “Let ’em have it.” Hit with the force of the water, children fell to the streets, some spinning under its power. Officers unleashed snarling dogs on the kids. Connor delighted in the fright caused by police dogs; he liked, he said, to see the “niggers run.” Policemen also attacked the children with clubs. These men brutalized scores of children at Connor’s command, some of whom lost flesh as a result of the water pressure, while others sustained bites and gashes from the dog attacks. Many onlookers responded to this violence with more violence, pelting officers with bricks and rocks. Amid the bedlam, Connor ordered hundreds of arrests. Police cars, police wagons, and school buses again carted hundreds of children off to jails and juvenile detention facilities. When the pens at these facilities overflowed, Connor held the young activists at the local fairgrounds. The same scene played out again later that week.

Over the airwaves and on live television, in domestic and foreign newspapers, journalists disseminated the scenes and sounds of children as young as six mowed down, clubbed, and dragged off to jail. The images from Birmingham shocked the world. Photographs and video footage showed the depth to which human beings would sink to defend white supremacy. By focusing a harsh light on the severity of the problem of American racism, the Children’s Crusade marked a turning point in the civil rights movement.

The travails of the child activists did not end there. In a stunning act of retaliation, Birmingham’s school superintendent, Theo R. Wright, in a May 20 letter to principals, ordered the immediate expulsion or suspension of all students who had joined the Children’s Crusade. Three members of the board of education — each of whom had been appointed by Connor — endorsed the superintendent’s decision..

Wright’s order dispensed with the due process requirement found in the same policy he relied on to oust the students. In the case of the Children’s Crusade, Wright observed, the board members had made an exception to the rule that entitled students to hearings prior to suspension or expulsion because “there is not enough time remaining during the present school session to have trials of all of these students.” The school year was set to end on May 30, 1963, 10 days after the superintendent’s fateful letter. The students would not only be deprived of their due process rights: by making the suspensions and expulsions a part of their permanent academic records, the board of education ensured that the punishments would forever haunt them and imperil those who planned to graduate in the spring. Wright was making an example of the children.

The actions angered and frightened parents and students alike. Many students had joined the movement without the knowledge or approval of their parents. Uninvolved in the protests themselves, parents fretted. Many had warned against the participation of children in Project C, and now their fears had been realized. In a community with limited access to education and historically low high school graduation rates, many worried over what would become of their families’ livelihoods. King’s decision to involve the children drew intense criticism.

At this precarious moment, Motley — working once again with Greenberg and local counsel Orzell Billingsley Jr. and Arthur D. Shores — filed a lawsuit in federal court arguing that the board’s action violated the rights of all 1,080 students who had been penalized. Motley contended that by suspending or expelling participants in the Children’s Crusade, the superintendent and board of education had made the legal process an instrument of racial discrimination. She requested the reinstatement of every student.

***

A lawsuit required plaintiffs, and Motley found brave representatives of the cause and the case in Rev. Calvin Woods Sr. and his daughter Linda. Woods was a singular man. Called to the ministry while in elementary school, steeped in social activism, and a strong believer in “speaking to social issues,” he was a Baptist minister and a Birmingham native. He had been beaten, arrested, convicted, and sentenced to six months in prison for protesting the desegregation of Birmingham’s buses in 1956, although his sentence was eventually overturned. He cofounded, with Shuttlesworth, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, which was a cosponsor of Project C. Integrally involved in the campaign, Woods had also been beaten and arrested by the Birmingham police during the protests, and Ku Klux Klan members had spat in his face.

That Woods’s daughter joined the struggle for civil rights surprised no one. Hidden away in the back seat of the reverend’s Cadillac, Linda and her sister, both still in grade school, had traveled to protests with their father for years. Linda grew up watching her father’s brave exploits, and what she saw left an indelible impression on the young girl. The sight of whites “treating my dad so bad” when “all he was trying to do was to make things better for Blacks” “made” her “want to get involved.” Inspired by her father’s example, Linda seized the opportunity to do her part as a protester in the Children’s Crusade and after her arrest as plaintiff for the trial.

The judge, Clarence W. Allgood — a native of Birmingham and one of several segregationists whom President Kennedy chose for lifetime appointments to the bench — was disinclined to side with the children. That was clear to Motley soon upon arriving in his courtroom at 11 o’clock in the morning. Allgood waited until late in the afternoon to deny Motley’s request for the injunction.

As Motley watched the time pass, she grew agitated. She had no illusion that the court would side with the plaintiffs and planned to appeal the judge’s adverse ruling. Time was of the essence if she was to appeal that same day and spare the parents and children another day of anxious uncertainty. When Allgood finally announced his decision, it was exactly what Motley had expected.

But Motley was one step ahead. She had been so certain of the ruling and so determined to immediately appeal the decision, that she had taken an extraordinary step: she had alerted Chief Judge Elbert Tuttle of the Fifth Circuit to expect to receive her legal papers challenging Allgood’s decision. Tuttle, who by now had witnessed Motley try numerous cases, agreed to hear the appeal later that same afternoon. Motley planned to depart Birmingham for Atlanta, the location of the federal courthouse, on the last flight of the day in the afternoon. Allgood’s stalling made her afraid that she would be too late.

Shortly after 3:00 p.m., Motley rang Tuttle’s chambers to inform him that she would not be able to make it to Atlanta in time after all. “I’m afraid we won’t be able to get there today because the last plane has left.” But Tuttle’s next words surprised and delighted Motley. “No,” he said, “I checked the schedule, and there is one at 5 o’clock that will get you here by 6.” Tuttle promised Motley that he would hear her appeal at 7 p.m. The conversation — and the extraordinary deference the chief judge showed to Motley — illustrated the tremendous respect and goodwill the civil rights lawyer had earned. Motley arrived on time, and Tuttle vindicated the students — all 1,080 of them.

Just hours after Allgood’s ruling, Tuttle ordered the school superintendent to halt the suspensions and expulsions of the students involved in the Children’s Crusade. In comments from the bench, Tuttle chastised Allgood for ignoring clearly relevant U.S. Supreme Court precedent. In decisions issued earlier that same week, the justices had reversed the convictions of activists who had been arrested while staging sit-ins at segregated lunch counters. Given the high court’s decision, Tuttle — visibly angry and exasperated with the school board’s attorneys — said the students had been illegally arrested for doing nothing more than exercising their constitutional rights. Tuttle called it “shocking” that they had been thrown out of school, particularly at a time of national alarm about school dropouts. The New York Times called Tuttle’s decision a “sharp rebuke” of the Birmingham judge and, by extension, of the superintendent of schools.

Following Tuttle’s initial decision, a three-judge panel of the Fifth Circuit issued an opinion formally reversing Allgood’s decision. The court had sided with Motley. The Crusaders would not be punished for protesting Jim Crow and would return to school.

Copyright © 2022 by Tomiko Brown-Nagin. Published by arrangement with Pantheon Books, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.