Irene Peirano Garrison teaches “Doing Things with Latin: Syntax and Stylistics.”

Photos by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Finding modern issues in study of ancient world

Professor’s research while developing Latin course turns up surprising insights into political, gender, racial, religious identity

In 1888, the process of awarding the prestigious Bowdoin Prize began routinely: Harvard students anonymously submitted their best essays in English or translated into Greek or Latin in hopes of receiving the honor and impressive sum of as much as $100. Contest judges also assessed essays submitted by female students at the University’s “Annex” (later Radcliffe College), but the winners didn’t receive University recognition or funds — an outside donor supplied an award of $30.

By accident or subversion (the events were disputed in The Crimson), the men’s and women’s papers were submitted together that year, and a classics essay called “The Roman Senate Under the Empire” by E.B. Pearson received top prize. It was quickly discovered that Pearson was actually Miss E.B. Pearson. The faculty swiftly ruled out her piece for contention, and the runner-up (a man) received $75 in her stead. Pearson received the $30 Annex prize, “thus paying $70 outright for the privilege of being a woman,” according to a Boston Post newspaper article from the time.

The incident was one of many surprising and thought-provoking discoveries in Harvard’s history of classics education for Irene Peirano Garrison while she developed the new Latin prose composition course, “Doing Things with Latin: Syntax and Stylistics.”

“Students at Harvard have learned to write in Latin since the founding of the University in 1636, and in planning the course I began by looking at the history of how, why, and to whom the Latin language, and specifically Latin composition, was taught at Harvard,” said Peirano Garrison, Pope Professor of the Latin Language and director of graduate studies in the classics.

Peirano Garrison wanted to include stories like that of Pearson and the gendered restrictions of the Bowdoin Prize along with more traditional aspects of classics pedagogy in the class, because “I realized that one could tell the history of the University, and even arguably of higher education, through the lens of how Latin was taught at Harvard.”

When she joined the Classics Department last January, Peirano Garrison learned that plans were underway to replace longstanding Latin composition courses “Latin H” and “Latin K,” which had been in place since 1948 and had a reputation for being difficult and technical. She saw an opportunity to build a composition syllabus that was “process-oriented, rather than outcome-oriented.”

“I had thought of Latin prose composition as a very old-fashioned exercise, but what I discovered is a complex and fascinating political history and one in which Latin instruction is deeply entangled with political, gender, racial, and religious identity,” she said. “It was important to me to give students opportunities to learn from writing in Latin as much as to learn Latin itself,” she said.

Like in a traditional composition class, students read and translated passages from authors including Cicero and Caesar. Unlike a traditional course, they kept personal journals of their thoughts on what they were learning. They also analyzed the style, syntax, and grammar of original works of antiquity and their English translations to see how texts upheld certain assumptions about identity and behavior.

“I had thought of Latin prose composition as a very old-fashioned exercise, but what I discovered is a complex and fascinating political history.”

Irene Peirano Garrison, Pope Professor of the Latin Language

Peirano Garrison noted that many texts used phrasing and syntax that linked masculinity with strength, femininity with beauty, and enslavement with docility.

“Again and again, we saw how very technical and matter-of fact topics of grammar can be politically charged because of assumptions about the learner or the outcome of education,” she said.

That holistic learning focus took the class out of the classroom throughout the semester. Students visited the Old Burying Ground to read tombstone epitaphs for former Harvard presidents and composed an epitaph for the presidents’ wives, many of whom were not given honorary epigraph in Latin. Another trip took them to Sanders Theatre and Memorial Hall to read inscriptions engraved on the walls honoring Harvard students who died fighting in the Union Army during the Civil War. Those inscriptions served as a foundation for an assignment to write an inscription honoring lives lost to COVID-19. A trip to the Institute of Contemporary Art prompted students to write commentary on fashion designer Virgil Abloh’s style and Cicero and Quintilian’s writing on style in the visual and literary arts.

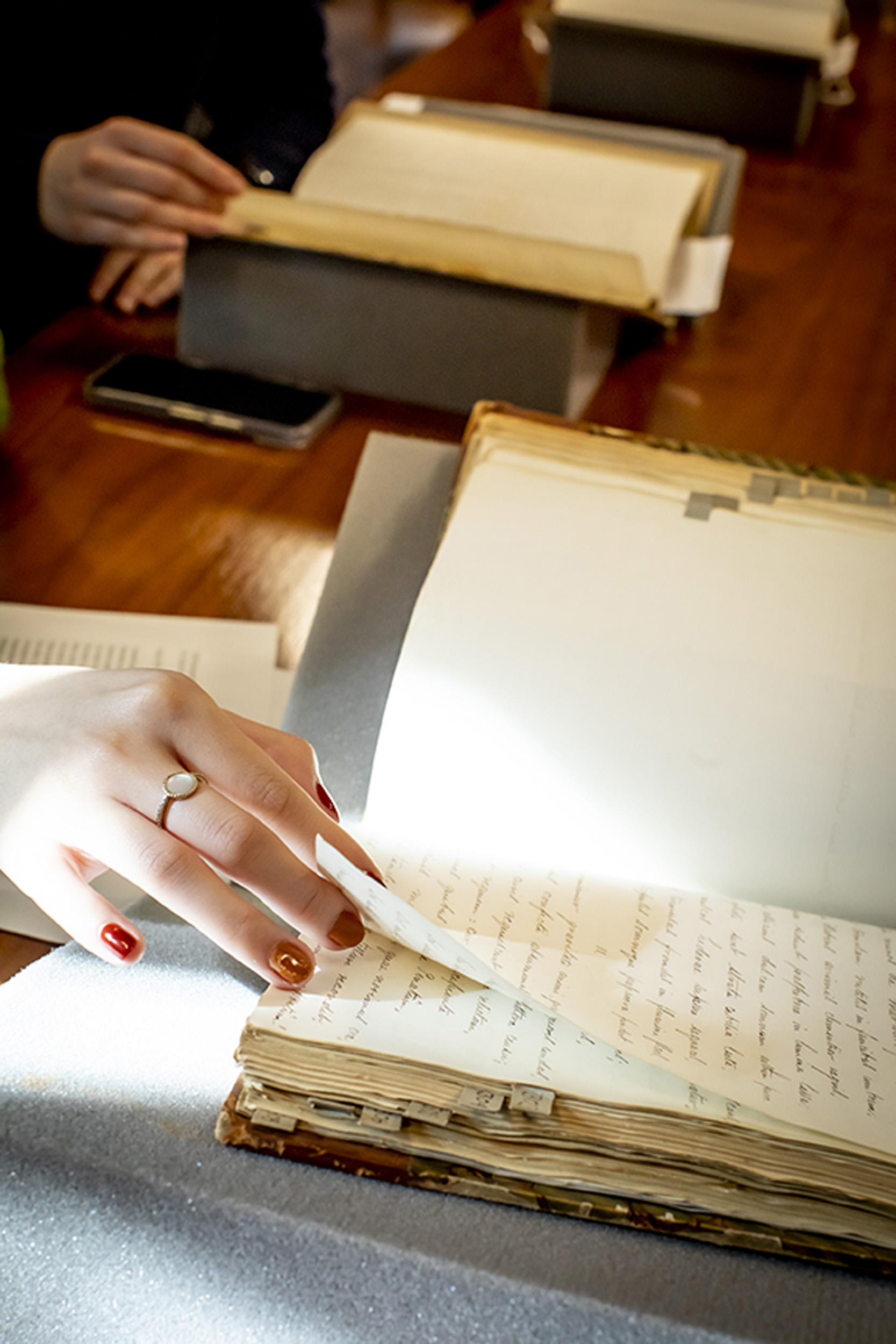

Students refer to Latin texts at Houghton Library. “I could not have done this class without the archivists and librarians,” said Peirano Garrison, pictured leading class.

Students also visited the Houghton, Gutman, and Schlesinger Libraries, and Harvard Archives to read Latin textbooks, student workbooks, Commencement addresses, and other materials from the last four centuries.

“I could not have done this class without the archivists and librarians,” said Peirano Garrison. “They showed me how this could be done and helped us gain access to amazing materials.”

In those settings, the class studied Latin translations written by W.E.B. Du Bois, analyzed classics research papers by feminist poet and Radcliffe student Adrienne Rich ’51, and read historical student works that debated the value of Latin education over the centuries.

“Doing Things with Latin” gave Dante Minutillo ’24, a classics concentrator, a new appreciation for the complexities of the history of education and Latin’s place in the Harvard experience.

“It’s easy to say that everyone at Harvard was really good at Latin in the past, and part of that was because they had a lot more practice. Or you could say that back then everyone respected Latin, and now everyone is criticizing it,” said Minutillo. “But if you actually look at it, there were debates even years ago as to whether Latin should even be taught. So it’s interesting to see how that’s more continuous than it sometimes seems.”

“It was really important to talk about practices of resistance and contestation that can be gleaned from and through the record of Latin education at Harvard,” said Peirano Garrison. “So many of the historical student works in Latin that we read touched on the very topic of education and its purposes. Those students then used the Latin class to question what they saw around them, as did some educators. I wanted my students to see how that happened so they can be attuned to the politics of their own classroom spaces.”

Peirano Garrison’s course is one of many offered in the Classics Department that engages with both ancient and contemporary questions, said David Elmer, Eliot Professor of Greek Literature and department chair.

“Although classics, as a field, is obviously rooted in the past, it speaks to the present in countless ways,” Elmer said. “Our course offerings are heavily shaped by the latest research of our faculty members, and every year we canvass our students to identify emerging areas of interest.”

Some of those avenues of interest are seen in the department’s spring offerings, including Elmer’s course “Classics, Race, and Power,” which covers race and oppression in the Greco-Roman world, and the Gen Ed class “Tragedy Today,” which is taught by Naomi Weiss, Gardner Cowles Associate Professor of the Humanities, and uses ancient Greek tragedy as a lens to investigate current sociopolitical issues including race, conflict, and immigration.

Peirano Garrison said students should, and can, engage with the classics and understand their role in shaping the political, cultural, and academic spaces in which they spend their time.

“Latin is everywhere on campus: on buildings, student notebooks, commonplace books, letters, Commencement speeches and exercises and more,” she said. “Latin also formed the backbone of Western education for centuries, and it’s important to approach this record of cultural hegemony with a questioning spirit, and within that to engage with Latin pedagogy as a political phenomenon.”