Looking to develop creative content for potters unable to make it to Harvard’s ceramics studio in Allston, program director Kathy King enlisted her colleagues at the Harvard Art Museums to help her.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Bringing ancient pottery to life

Zoom pottery class enlists Harvard Art Museums experts to help re-create treasures from the collection

How do you teach a pottery class on Zoom? You get creative.

During the lockdown Kathy King, director of the Ceramics Program in Harvard’s Office for the Arts, wanted to develop engaging content for potters unable to visit the program’s Allston studio. So, she called her friends at the Harvard Art Museums.

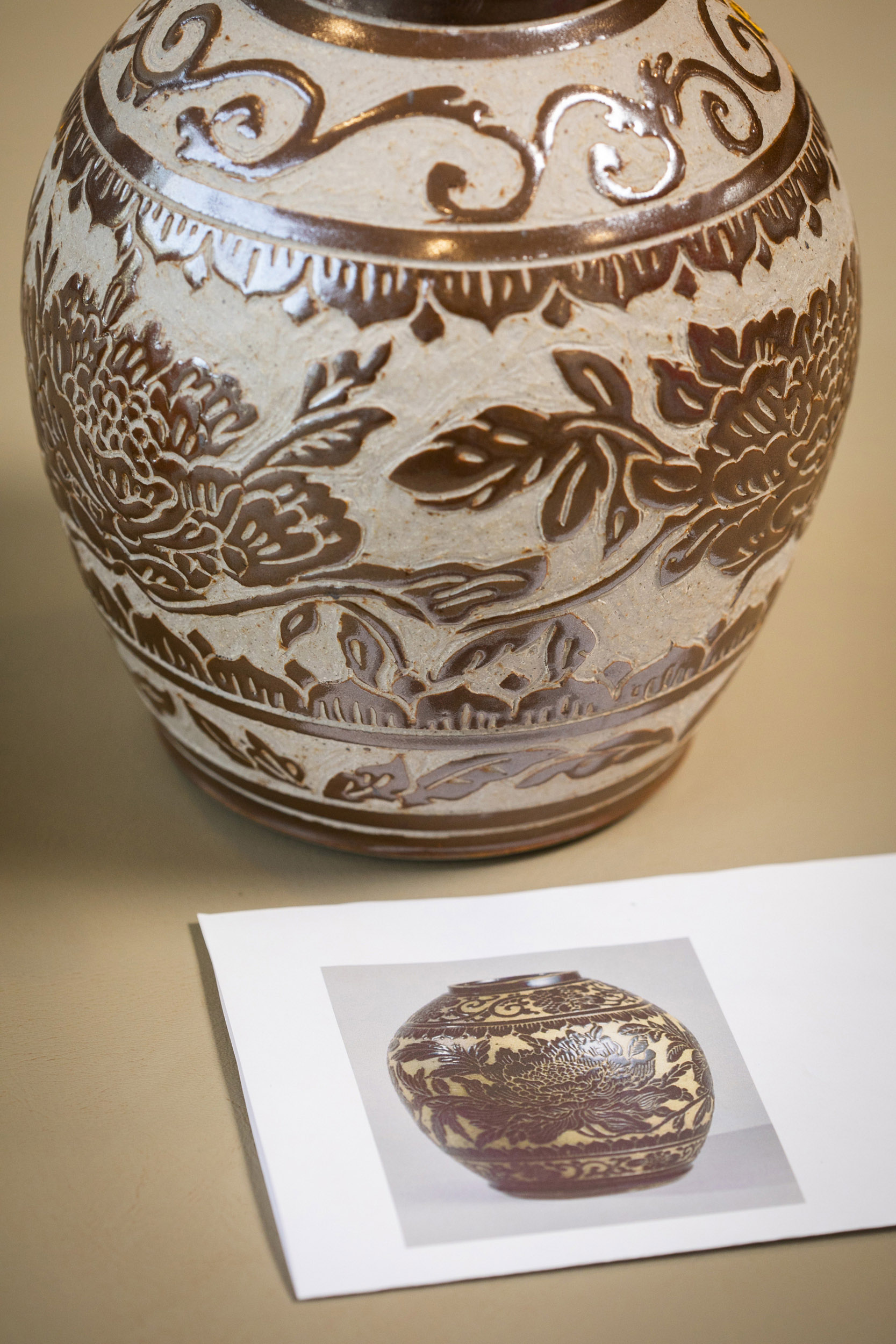

The resulting adult-community course — a blend of art history and hands-on, albeit virtual, instruction — brought some items from the museums’ collections to life. For eight weeks this summer King, along with master potter Denny McLaughlin, an instructor in the program, and numerous museums curators and art conservators examined a range of works, studying their history, and demonstrating the different clay potting and sculpting methods used in their creation, some dating back centuries.

“It’s so exciting to realize at the end of the day that the same techniques, created through time and different cultures with this one material, are so similar,” said King.

The course was a hit with local potters and with potters from Canada, South Africa, Finland, Europe, the United States, and beyond. The remote students set up makeshift studios in their kitchens, basements, or backyards and tuned in to listen to curators discuss a sampling of Harvard’s porcelain treasures, and to watch over Zoom as McLaughlin re-created them in the studio.

Then, it was their turn.

“Normally you don’t want people to replicate things, you don’t want people to copy things,” said King. “But in this exercise, it was so wonderful to have people take the techniques that they’re familiar with and try and challenge themselves to create something they would normally never make. It really helps them build stronger skills.”

The course was also a boon for museum staff who observed McLaughlin’s careful demonstrations to learn about the materials and the methods used in a range of different works, and to appreciate the makers’ expertise. “It’s been like gold for us because we love to know how things are made,” said Angela Chang, a specialist in the conservation of objects and sculpture at the Harvard Art Museums. “The time and skills required are not readily apparent when we study a finished product. A maker’s perspective provides invaluable insight for curators and conservators in their research and interpretation.”

Before the online sessions began Chang and McLaughlin examined the works selected for each class in the museums’ Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. Together they carefully studied the exterior details and reviewed X-rays of the pots, bowls, jars, and vases for any hidden clues.

For McLaughlin the course was part detective story, part science project.

To replicate the textured glaze on a pitcher from the 15th century, he opted for a soda-firing process that could turn the final product a mottled, blueish gray typical of the traditional salt-firing, minus the noxious by-product sodium chloride.

A set of examples created by Denny McLaughlin to replicate pieces from the Harvard Art Museums collection.

By looking closely at an Etruscan kantharos dating from the sixth century B.C.E., he and Chang found that instead of being crafted on a wheel from one lump of clay as they had initially believed, the cup is actually an elegant mix of several thrown and hand-formed pieces. The clue? A small rim on the inside of the vessel. “If a maker plans to intentionally throw a bowl,” said McLaughlin, “such a ridge doesn’t make sense. Instead, it looks like there are three distinct pieces, a plate, a bowl, and a stem,” he explained, “that were combined to give it this fascinating shape.”

Trial and error were also key parts of the process for McLaughlin, who needed multiple attempts to produce the exact consistency of slip — a watery clay — used to create the vine-like design on a Roman beaker. He also had to guess at the kind of tool the original maker might have used to apply the slip to the jar’s surface. In the end, a soft bristled brush created the desired effect. To prepare for another session McLaughlin repeatedly mixed and matched different colored clays to capture the exact blue-black hue of the museum’s evocative Portland Vase. He wasn’t alone. The original designers of the intricate Wedgwood piece from the late 1700s, modeled after a Greco-Roman vase of cameo glass from the first century C.E., also struggled to get the look just right.

“It took years and years for the makers at Wedgwood to be able to make one,” said King.

McLaughlin said simply achieving an accurate base color was a success. “I am not even going to come close trying to re-create the piece,” he said. “I will take a shot at the form, but as far as what’s done to the surface, it’s too exquisite.”

Those eager for a peek at some of the works created during the course can visit the reopened ceramics studio’s Gallery 224 by appointment, where a range of items crafted by ceramics instructors for their online programming during COVID are on display.