Master potter Ben Owen III demonstrates his throwing process and lectures on his work and role within the lineage of makers from Seagrove, N.C.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

“The most difficult part about being a potter is having that steady hand to work the clay,” master potter Ben Owen III tells an appreciative crowd at a recent workshop at the Harvard Ceramics Building in Allston.

The third-generation artisan from North Carolina dispensed advice and stories from behind the wheel as he shaped vases and teapots. “Major in the minors,” he said, encouraging the student and community potters to pay attention to the details.

“I have never seen a visiting artist make as many works in such a short amount of time,” said Kathy King, director of education for the ceramics program. “This enthusiasm for his craft and generosity in sharing his techniques was impressive.”

Owen said his grandfather began teaching him pottery when he was 9 years old. He would say, “Each pot is a sketch for the next one.”

“Ben Owen III is an example of a traditional potter with a deep connection to this country,” says Kathy King, director of education at the Harvard Ceramics Program. “Countries such as Japan, Korea, and China all celebrate their family potteries and the work is considered to be part of a lineage. In the U.S., we also have these families, oftentimes originating in the Southern U.S. The importance of the skills and craft of working with clay being passed down is certainly something to be celebrated, and Ben embodied that pride, as seen in his stories and visual presentation.”

Owen recalled being 13 when his grandfather was bedridden with arthritis and leg pain from years at the kick wheel, worsened by a cold. The teenager snuck out to the studio with one of his elder’s teapots to use as a model, and made three of his own.

“I did the best I could with my skill,” Owen said. “I took them into the house to show him. I was so proud to show him I made three teapots.

“He sat right up, and he had been in the bed most of the day. … ‘You made your knob too small. You made your handle too thin. You made your spout too big.’ And the next day he was right back out there with me. ‘We’re going to try these teapots again.’” Owen laughed. “The reason why my grandfather lived longer was he never knew what I was going to do next. He was such a great mentor.”

Graduate student Ana Paula Hirano, a relative newcomer to pottery, said she learned new techniques from Owen, such as using a potter’s tool called the rib to dry the clay.

“He talked about how he wedges, and how that creates a certain spiral on the clay,” added Alex Kim ’21. “He then showed us how putting that spiral on the wheel in the wrong direction can have an effect on the structural quality of a clay piece. … I am eager to apply this new method to my craft.”

“The most difficult part about being a potter is having that steady hand to work the clay,” Ben Owen says, “not to abruptly bump it, the way that you touch the clay with the rib or your fingers, and the way you release the clay and take your fingers off.”

Ben Owen says attention to detail allows potters to take their skills to another level.

“How does one become a master potter? Well, you must be deemed a master by another master potter,” Kathy King says, “which typically entails being part of a system of apprenticeship that involves years of study and dedication.”

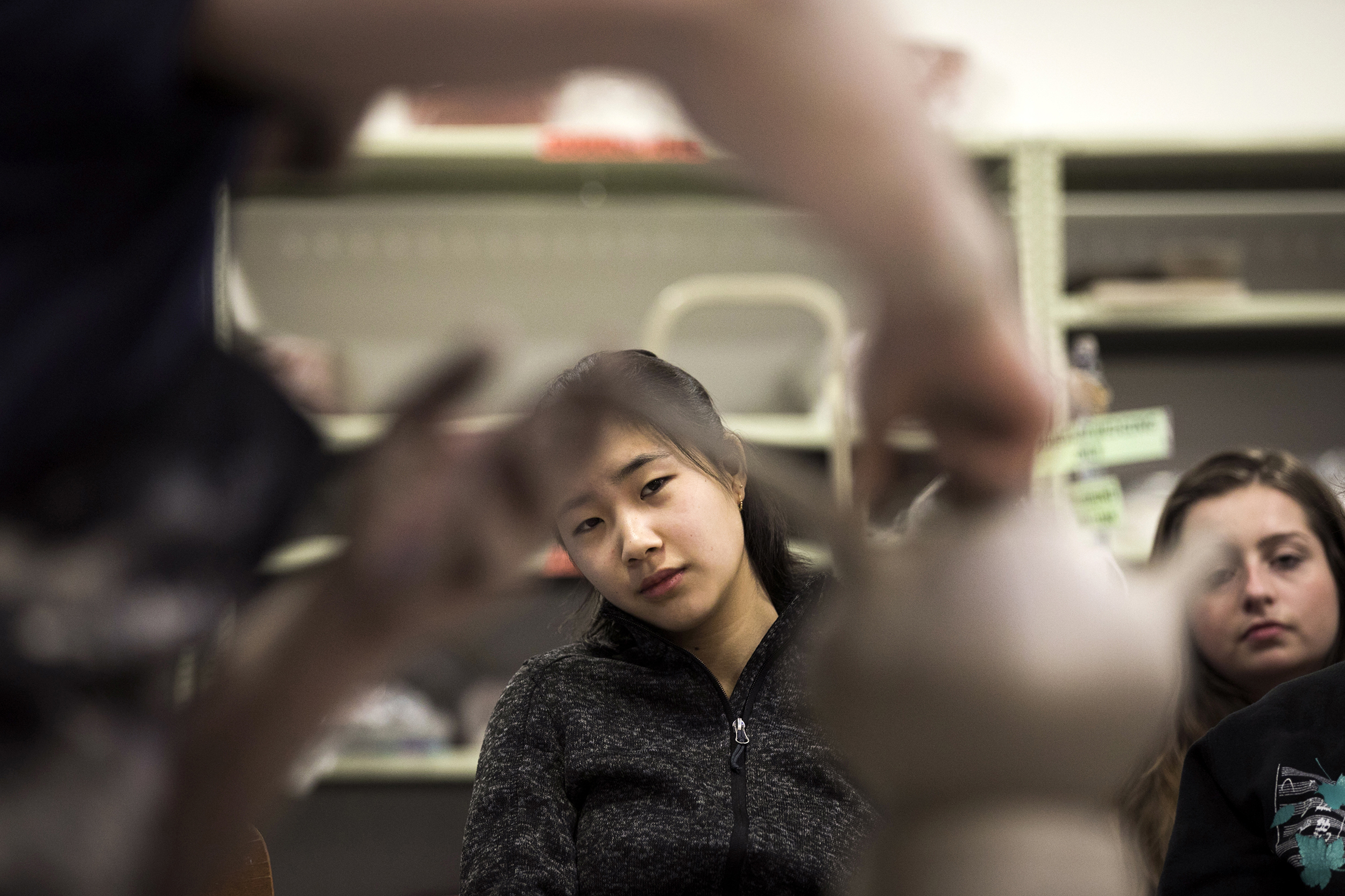

Graduate student Ana Paula Hirano watches Ben Owen craft a teapot. Altering the surface, Owen says, “begins to give a different life to the clay, something like you would see in the garden, a cantaloupe or a pumpkin form.”

“My impression of his work is that every step is important to him; from start to finish he pays attention to each detail, and I think that adds a refined and unique quality to his outcomes,” says Alex Kim ’21. “I loved listening to him talk about his background of coming from a long line of dedicated potters, and how impactful the relationship with his grandfather was to Ben’s artwork.”