With digital archive, a time and a new way to understand colonial history

Musical composition titled “Washington’s March” by a Portsmouth, New Hampshire merchant named John Wendell, written in the mid-late 1700s.

Images courtesy of Harvard Library

‘Worlds of Change’ puts new focus on the everyday and unrepresented

In a recent virtual curatorial discussion, Houghton librarian John Overholt took an item from the Colonial North America collections to share with his audience. Rather than highlighting a letter from John Hancock or a cameo of George Washington, Overholt chose a yellowed piece of paper with a faded inventory from a sugar plantation in Antigua. The plantation’s owner, Slingsby Bethell, had listed the plantation’s enslaved people as though they were cattle or sheaves of wheat.

Speaking to why he chose this item from hundreds of thousands in the colonial-era collection, Overholt explained, “In a system designed to erase every trace of enslaved peoples’ humanity, this is one of the few records of it.”

The record exists digitally now because, nearly 10 years ago, Harvard Library began a project to digitize all its unpublished 17th- and 18th-century manuscripts and archives related to colonial North America. This turned out to mean more than 700,000 pages of material, from the seemingly mundane to those related to well-known historical figures.

The digitization project was finished this spring, and Harvard Library staff and partners from other institutions celebrated its completion with a virtual symposium in early April. A key theme of the symposium was reflecting on the upper-class, British, male-centric view through which many American students learn about the colonial era — and the opportunities to change this. Harvard curators argue that free, digital collections like this one provide a chance to change how we think, learn, and teach when it comes to colonial North America.

For University archivist Megan Sniffin-Marinoff, who has worked on the project since it began, a goal has always been to capture a breadth of materials that depict daily, “normal” life.

“There was no cherry-picking, no hand-selection of special items, and we wanted to focus mostly on unpublished manuscripts and archives,” Sniffin-Marinoff said. The breadth of the collection, which is centered on North American experiences but contains stories from across the globe, inspired its new title, “Worlds of Change.”

The new title was introduced at April’s symposium and is also descriptive of the colonial era — a world of unprecedented connections and encounters between peoples that caused dramatic change at the time, changes that still reverberate in the present.

The digitized collection includes vaccination records and written medical advice, court documents and bills of sale, church congregation listings and school awards. There are pieces of music, poems, and recipes. There are young women’s journal entries, letters between friends, and correspondence between colonists and Indigenous people.

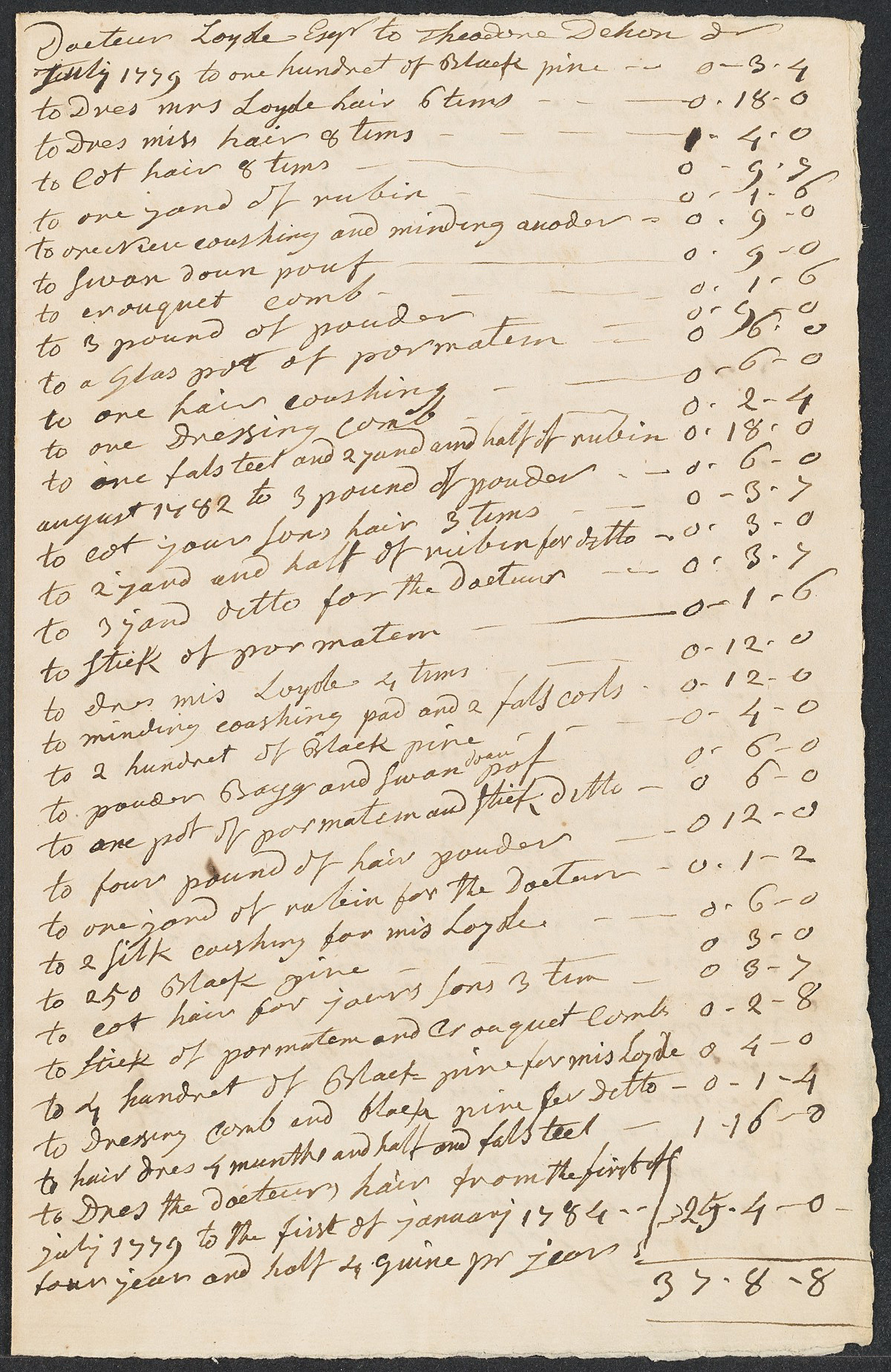

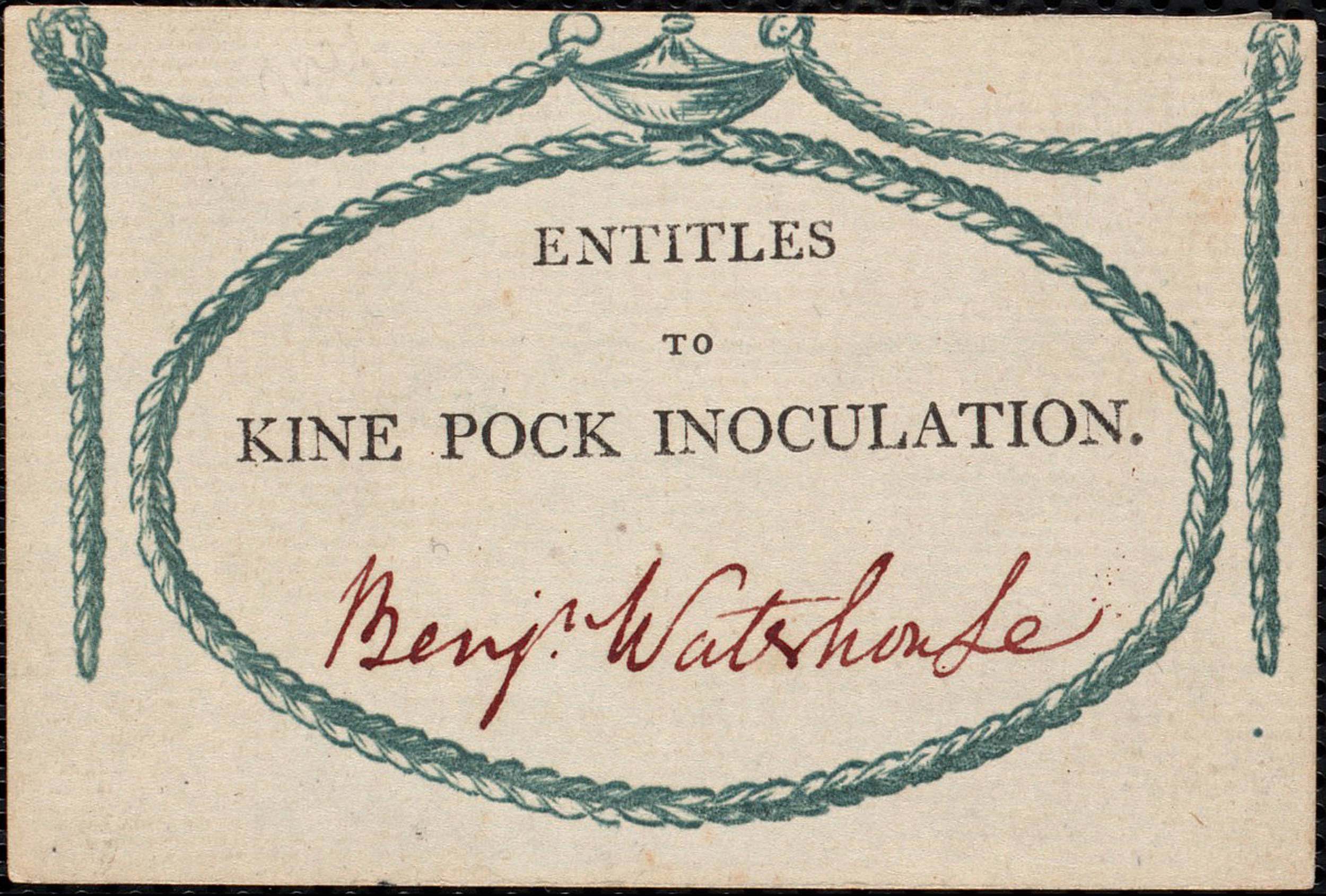

A 1787 bill for services to Dr. James Lloyd and his family by hairdresser Theodore Deshon, including haircuts, hairstyling, and materials like combs, powder, and swan’s down poufs. Card issued by physician and Harvard Medical School professor Benjamin Waterhouse in the late 1700s-early 1800s, entitling the card bearer to be inoculated against “kine pox,” another name for cowpox.

In seeing how much there is, Sniffin-Marinoff said, it’s also important to look at what — and who — is not mentioned in the records. The last names of the enslaved people listed in the Antigua plantation record are not preserved in the inventory, let alone their correspondence.

“This collection is not a full representation of all society at the time,” Sniffin-Marinoff said. “We have more records on women, Black Americans, and Native Americans than we realized, but it’s never going to be a full representation.”

At the symposium, keynote speaker Karin Wulf quoted Caribbean historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot, who said, “The presences and absences in archival sources … are neither neutral nor natural; they are created.”

“The archives of North America have been shouting at us for centuries,” said Wulf, an American historian and the executive director of the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture at the College of William & Mary. “They have been telling us that British America is the most important, that the public deeds of the powerful are more important than the regular deeds of the ordinary, that some people are named, and many are not.”

For scholars today, it is much more difficult to find and study records on the daily lives of people in the 17th and 18th centuries, especially groups like women, enslaved people, and Indigenous people. The good news, Sniffin-Marinoff said, is that digitization of materials makes the records that do exist much more accessible.

“One of the great benefits of this project is that we were able to bring to the surface some of these things that were hidden or not easily accessible,” she said. “The more you dig into these materials, while you’re not going to find the words of an enslaved person, there’s evidence of them, their lives and their work.”

Stephen Curley, the director of digital archives at the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, knows the importance of digitizing diverse materials. His organization is working to digitize and centralize archives from several hundred 19th- to 20th-century boarding schools for Native American children.

In his previous role as archivist for the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe, Curley worked with Harvard curators adding context to materials related to Wampanoag people in the Colonial North America collection.

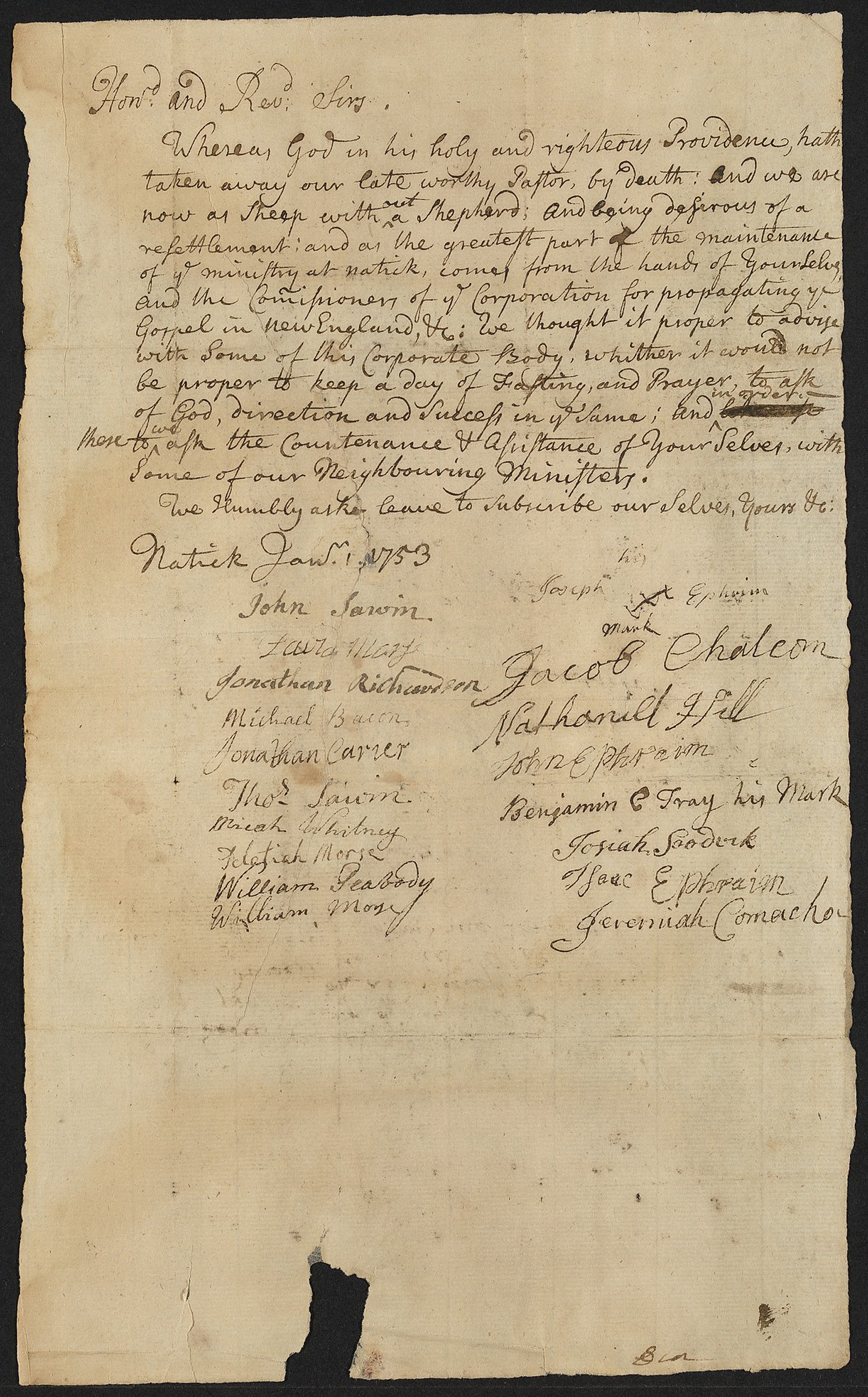

A 1753 letter to the Harvard Corporation about a recently deceased pastor, from representatives of Indigenous people in Natick, Massachusetts.

“These more-obscure pieces of primary source material need to be examined,” Curley said during a panel at the virtual symposium. “Digitization is a vehicle for ensuring we have time to examine niche pieces of history that add to mainstream historiographies and sometimes complicate our history of what’s been written.”

But with every opportunity comes questions and challenges. Digitizing materials by and about underrepresented groups can be empowering for these groups, Curley said, but only if they’re included in the process and have a say in whether some materials should not be publicly available online.

Vincent Brown, the Charles Warren Professor of History and Professor of African and African American Studies at Harvard, noted that archival context is important, and can be easy to lose with digital materials.

At the symposium, Brown said that “there is virtue in looking through archives and seeing what items are adjacent to each other,” as well as thinking about why and how they were placed where they are.

“Sometimes using a keyword search doesn’t tell you any of those things,” he said. “How are we going to train people to ask questions of these materials that will make them as informative and accessible as they need to be?”

As they ponder this question, Harvard’s archivists are doing ongoing work to make the digitized materials usable by as many people as possible.

Creating the curated website with users in mind was a huge first step, said Sniffin-Marinoff. Now they are working to improve accessibility by transcribing a selection of the collection’s written materials. The transcribed texts will also serve to automate handwriting recognition in the future, further expanding accessibility.

Associate University archivist for community outreach Ross Mulcare is also eager to engage a variety of communities with the digital “Worlds of Change” collection. He is working on creative ways to connect collection materials with students, scholars, and researchers around the world.

“All of the complexities of early American history are represented in the ‘Worlds of Change’ materials,” Mulcare said. “Analyzing and explaining those complexities is the task of researchers of all types and all perspectives, and I’m excited to see what new insights into the period are generated from these materials.”

Sniffin-Marinoff agreed.

“This period was far more complex than most of us learned about in high school,” she said, “and that is becoming clearer the more historians dig into collections like this one. I think this is part of a turning point to completely reassess this period in American history.”