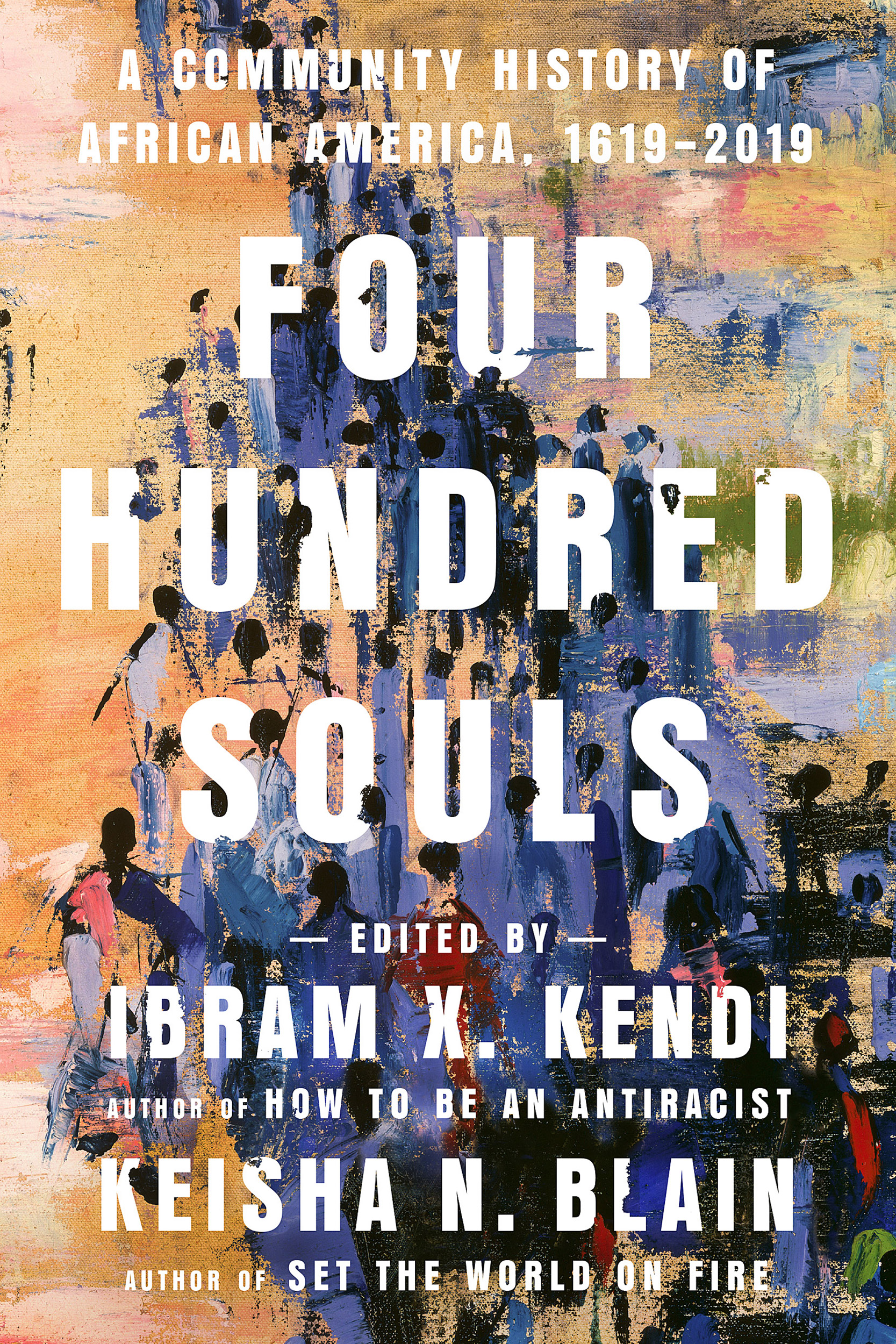

Keisha N. Blain is a historian and fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard University.

Wikicommons/Public Domain

A 400-year community chronicle of African America

Historian details issues in editing collection of historical and personal essays, stories, and poems

Historians Keisha N. Blain and Ibram X. Kendi began working on “Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019” in 2018. The best-selling collection, co-edited by Kendi, author of “How to Be an Antiracist,” and Blain, author of “Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom,” features 80 short historical pieces, personal essays, stories, and 10 poems by prominent Black writers. Told in five-year increments, the work offers a varied look at four centuries of the African American experience.

Blain, associate professor at the University of Pittsburgh and a fellow at Harvard Kennedy School’s Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, will discuss the new anthology with Annette Gordon-Reed, the Carl M. Loeb University Professor and professor of history, and Jarvis R. Givens, assistant professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the Suzanne Young Murray Assistant Professor at Harvard Radcliffe Institute, on April 23. The event is sponsored by the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research.

The Gazette spoke with Blain about the work in a recent interview.

Q&A

Keisha N. Blain

GAZETTE: How did this project originate?

BLAIN: Ibram and I have been working together in various contexts for several years, but this collaboration is certainly the biggest. In 2018, he reached out to me to ask if I would be interested in working with him on this project as a way to commemorate 2019 as the 400-year mark of what can be described as the symbolic birthdate of Black America. Certainly, as you know, people of African descent were present in the territory that would become the United States before 1619. But 1619 is still a pivotal year, as we explain in the book, for a wide range of reasons.

We moved rather quickly in the fall of 2018 to put the proposal together and sketch out a plan. From the beginning, we knew we certainly wanted all of the writers to be people of African descent. We also knew from the beginning that we wanted 80 writers contributing essays, plus 10 writing poems to conclude each section. The idea was that each writer would grapple with only five years, so there would be some uniformity. We also initially put together a very long list of writers, both writers he wanted and writers I wanted, and then we talked through the process of who we’d actually ask and what we’d ask them to write about.

GAZETTE: The group of writers you’ve included have incredibly diverse backgrounds and professional interests, and they address their pieces in very different ways. Can you talk about that approach?

BLAIN: We wanted this book to have the broadest possible reach. I think that’s the best way to explain it. We wanted this to certainly be a book that historians would find value in, that students would be able to appreciate. But even more so, we wanted to capture the attention of the ordinary reader, the ordinary American who might not have a lot of interest in history, but who might be pulled to the project because they noticed the fact that it included poetry, or writers from their fields of interest, or other topics that might be of interest to them. So we weren’t putting together a book that would simply bring together professional historians, but one that would bring together a community, a diverse community of writers from various backgrounds who could approach each topic differently, and who could help us capture a wide range of genres.

We tried to feature historical essays, certainly, but also personal narratives appear in the book, which is intentional, because for some readers, those personal narratives could be far more effective in conveying the ideas than a typical historical essay. So it was pulling together a diverse community of writers to represent the diversity of Black writers, and similarly, the diversity of Black America. And then at the same time, being able to reach a diverse and broad readership interested in a number of themes that we grapple with, including race, politics, and activism.

GAZETTE: Women are featured prominently in the collection. Was that part of the plan?

BLAIN: Yes, this was also intentional. The decision to only ask writers of African descent to contribute was really intentional to the larger goals of the community vision that we had. And the second goal was to make sure that we had a significant number of women writers contributing because we wanted to counter the way that standard historical accounts are often told through the lens of male historians, or male writers broadly. It was important to invite this many women writers in order to capture their voices and, in so doing, also capture a number of themes that directly concerned women. And so it’s not surprising that feminism as a theme comes up in various pieces, as does the Black family, sexuality, and various other topics. The other point I would emphasize is that we were also thinking about — and this is true certainly in 2018, and it became all the more urgent as things progressed — the Black Lives Matters movement and the crucial role that women played as founders of the movement and continue to play as local leaders. We knew that we would end the book with Black Lives Matter. So in a way, the focus on so many women writers was also a way to push the point that Black women have been vital in American history and in shaping modern American politics.

GAZETTE: Were there any essays in particular that really struck, or surprised you?

BLAIN: I love all of the pieces in the volume, but Kiese Laymon’s essay on cotton, which covers 1804 to 1809, was surprising. Of course, we knew that the 1804 to 1809 period was, in some ways, arbitrary because one could cover cotton as a topic for decades, and certainly the 1804 to 1809 period is not even considered the most important in tracing the development of cotton production in the U.S. We knew that, but part of what we wanted to do was allow Kiese the space to be creative, and that’s exactly what he did. In it, he talks about his grandmother. He talks about there being cotton in her household when he was growing up. He talks about how it became such an important part of his childhood, of his upbringing; what it meant not just for Black people in Mississippi, but what it meant for him. And then, he connects it to the history of slavery, to the Southern economy. It ended up being a very moving essay, and one that he then connected to the present and his own experience. The essay ends with him being at the University of Mississippi and driving by acres of cotton.

So he took this topic, gave us a glimpse of its significance within the 19th century, but then connected to his own life and his own narrative growing up in Mississippi from childhood to the present. And he wrote it in such a beautiful way that it just stuck with me. When I read it for the first time, I remember being so moved by it I didn’t even mark one thing on the page, and I was supposed to be editing it. I just thought, “I have nothing to add to this because it’s so remarkable.” So many readers have told me over the last couple of weeks and months that that piece really moved them.

“We wanted this to certainly be a book that historians would find value in, that students would be able to appreciate. But even more so, we wanted to capture the attention of the ordinary reader …”

GAZETTE: How did you land on the idea of five-year increments, and did you have a topic in mind for each writer to address?

BLAIN: Ibram and I had lots of conversations, looking at who we had on the list, and deciding what exactly each person would write about. We had ideas when we started about what each person could cover. In some cases, we wanted someone to write about a topic that was squarely within their field of expertise. For example, asking Isabel Wilkerson to write about the Great Migration was an easy ask since she’s written a remarkable book on the subject. So that made sense.

For other people, it was about focusing on a topic that they may have written about, but perhaps in a different time period, so getting them to step back a bit and grapple with, say, rebellion in the 19th century when they generally talk about political agitation in the present moment. We had mapped all of this out, and the ask was simply, “Would you write on this period and on this topic?” Not surprisingly, many people responded and said, “I would love to do this, but I don’t love the topic.” Whenever we received that response, we would get on the phone and ask them what they had in mind and why they thought it was more compelling. So it was a certainly a negotiation in some cases. There were writers who ended up writing on topics that we had not planned, but they made a strong case for it, and it worked. It just meant that if we gave up a particular topic, we tried to find a way to weave it into another essay, because we wanted to make sure we still covered the same ground in terms of the core themes.

We did have a few people who said no because they hated the time period. One historian was particularly frustrated with the five-year arrangement. He said, “This is arbitrary; this is not useful.” We said, “Listen, we’re both historians. We understand how this works. But we’re asking you to bend a little. We know that these five years are not perfect in the narrative that you’re supposed to tell. But can you play around with it?” And he just didn’t want to.

GAZETTE: In his essay on the Virginia Slave Codes covering the period of 1704 to 1709, Kai Wright writes “the past is close.” Connecting history to the present day is one of the themes running though the book. Can you say more about that?

BLAIN: Once we were clear on the topic people would write about, we gave them the same guidelines. We explained that we wanted them to certainly grapple with the history, but we also wanted them to think carefully about how the history that they were grappling with connects so deeply with current day developments. We wanted the book to contextualize the contemporary moment. As it turns out, in the process of putting the book together, so much happened in those last few months — COVID-19, which we could not have foreseen, and then the uprisings. And because we were already asking writers to look back and connect to the present, it all came together. So now there are actually essays in the volume that give you a glimpse into the history of medical racism, for example, that also offer you some context when you look at COVID data in the U.S., or even across the globe, and you see the connections to the political uprisings that took place in the spring and in the summer.

I think the other thing that’s so powerful about this project is the intergenerational dialogue. We were intentional as we thought through the diversity of writers. We knew it was important to reach out to folks who could write about movements, and moments in history of which they were at the center. So it made sense to ask Angela Davis to write about the Crime Bill and Charlie Cobb to talk about the Civil Rights Movement. Charlie wrote an essay about his contemporaries, his colleagues, the folks he fought with and marched with. Barbara Smith wrote about the Combahee River Collective, which she helped put together. So those essays reinforce the point about the past being close.

GAZETTE: Why did you choose to start each section of the book with a poem?

BLAIN: What we wanted to do, which I think is so important for a project this huge, is to provide a break for the reader. If you look at how it’s structured, the poem actually appears at the end of one section — essentially, it’s the bridge between the conclusion of one section and then the beginning of another. We asked each poet to read the essays within the sections in which their poem was placed, and that worked out very well because it meant that even though they were going to produce an original poem, it would be one that at least conveyed to the reader the core themes that stood out to them as they were reading those essays. I think it’s a nice device for cohesion, but it’s also a very good way to give the reader a break. Once they have gone through several historical essays and creative pieces, they have a shorter piece in a different genre and tone to grapple with before they move on to the next section. It was also a way to reach the reader who might get a lot more from a poem than any of the essays in the volume.

GAZETTE: You wrote the conclusion to the book. Was it difficult to try to come up with a way to end such a sweeping work?

BLAIN: Yes, it was very difficult to do. And, in fact, the conclusion that appears in the book ended up being the second version of the conclusion that I wrote. I wrote an initial ending rather early — I think it was sometime in January 2020, so before COVID-19 had spread in the United States. And I certainly had lots of things on my mind at the time, reflecting on the Trump presidency, and trying to look ahead and imagining what the future would hold, etc. And it was a useful conclusion. But I realized that I had to scrap it completely as we began working through the last few months of the project with COVID-19, which turned everyone’s life upside down, and then the uprisings.

I began writing the conclusion that ultimately appears in the book a few weeks after the police killing of George Floyd, which is now being prosecuted in court. I just remember feeling so broken, as many have felt, and in some ways frustrated and even angry about everything that was taking place. I thought I needed to write a conclusion to capture all of this pain and frustration, but one that would not leave people in complete despair. And so I was trying to strike the delicate balance of being honest about the challenges, honest about where we are collectively as Black people in America, and then also looking forward and hoping to give the reader a sense of hope to carry on and to push the fight forward for the next 400 years. So that’s what I was thinking at that point. I felt it was important to connect to my own personal narrative and to be very clear about some of the challenges of COVID-19 and police brutality, to name those things, and then also imagine what the future could hold.

GAZETTE: The book is dedicated “to all the souls taken by COVID-19.” Why did you choose that dedication?

BLAIN: That was also a decision we made at very end, right before we went to publication. We had written another dedication initially to our kids, and that made sense. But as we were bringing the book to a close and we were reading through the proofs one more time, we realized we had to shift away from ourselves, and that as much as we loved our relatives, we could thank them in the acknowledgments. We thought it was important to make a statement to acknowledge the national and global pain that people are dealing with. We wanted to honor the memory of those who passed away over the last year. And so this was a tribute to them. And I think it connects to the question you asked about the conclusion, because it’s about acknowledging the grief and the pain and yet trying to give a sense of hope. So it made sense to open up with that painful acknowledgement, and then to close with my conclusion to propel people to think about what it means to actually realize our ancestors’ wildest dreams.

Interview was edited for clarity and length.