Kathy Santoro in Marblehead, where she grew up. Her family still lives in the coastal town.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

A table set for two

It was crackers and Scrabble at the cottage and, later, dinnertime jokes at the care unit

Portraits of Loss

Kathy Santoro

A collection of stories and essays that illustrate the indelible mark left on our community by a pandemic that touched all our lives.

On March 11, at 7:30 at night, I texted my siblings because it had been exactly a year since I last saw my mother. She passed away last April 24 from COVID-19. Six weeks earlier on that first March 11, I’d visited my mother at her assisted living residence. I told her, “I’ll see you tomorrow, and I love you,” and she said, “I hope so.” And the next day, they shut the place down, and nobody could go see anyone.

I grew up in Marblehead, and my entire family is still in the area. After my father passed away in 2008, my mother downsized and moved into a tiny cottage — one of the oldest houses in Marblehead — next door to my house. She was very lonely and trying to keep herself busy, and she told me that she always looked forward to my father coming home from work at 5. So I thought: I can come home to her every night after work. I’d pull in my driveway, and she’d be waiting at the door. She’d go to her refrigerator, and she would have a little glass of wine with Saran Wrap on the top waiting there for me. She’d give me a little plate of some crackers and cheese or potato chips, and we would play Scrabble or other games. So I got into that routine with her.

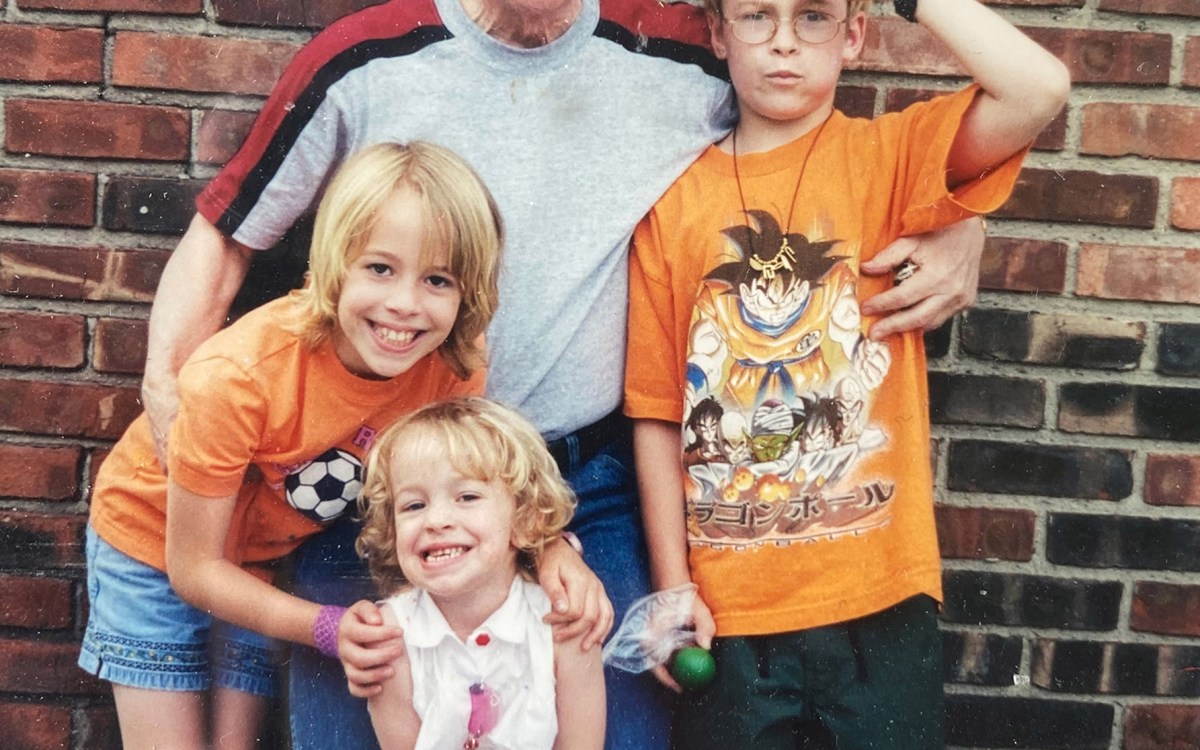

Kathy Santoro (right) with her mother, Jane Norris Faulkner.

Courtesy of Kathy Santoro

As she got older, her memory declined, and eventually she moved to a nice facility nearby. It was on my way home from work at Harvard, so it was easy for me to stop by and sit with her and play Scrabble or do a jigsaw puzzle, kind of like we always had. Later, she moved to a memory-care unit at the facility so we didn’t do that as much. But sometimes I would get there at dinnertime, which was always fun, because there was another woman whose husband would come in, and he and I would get on our phones and we would read jokes for them. Mom and I would watch television together, and I’d hold her hand. It was always a peaceful part of my day and hopefully for her too. She was a very sweet person, so it wasn’t all that hard to spend time with her.

More in this series

It was so isolating for the residents when the facility locked down, and it was so early in the pandemic that there were no set-ups for iPad visits or anything like that. She celebrated her 88th birthday on April 16, and on April 24 she passed away. At first she had a fever and didn’t feel well. They got her tested, and she was negative, but she didn’t get better. She got worse. Two days later they tested her again and sent her to the hospital, and she tested positive, so she must have had a false negative.

The day before she died, I called the floor nurse at the hospital to see if I could talk to my mother on the phone. I had the most incredible conversation with this person who said, “Your mother’s a lovely, beautiful, wonderful woman, and I’ve been with her, and I’ve held her hand.” I was just so grateful to this nurse for being there for her because I know that my mother did not like to be alone. Her facility had everyone in the entire building tested, and the National Guard came to do the testing. Fortunately, they identified the people who had tested positive, quarantined them, and nobody else got sick. As far as I know, my mother was the only person who died.

“I told her, ‘I’ll see you tomorrow, and I love you,’ and she said, ‘I hope so.’ And the next day, they shut the place down, and nobody could go see anyone.”

I didn’t know what to do when she was sick. I had all these Zoom meetings on my calendar for work, and I’d be in meetings with people talking about the virus, but I didn’t tell people that my mother had the virus because I didn’t want to freak people out. It was bad enough out there. I mentioned it to some people, and most of the time people would respond by telling me I should be with her. But I couldn’t be with her, so all I could do was just keep working. When I look back on it and I think about working through all of that, it was surreal. I don’t know any other way to describe it, because I was trying to digest the pandemic and have someone close to me die from it. It felt like a tidal wave.

For a few months, we had no obituary. We had no funeral. My family couldn’t convene together. We didn’t expect the pandemic to go on for so long, but eventually we decided we needed to have some closure, so in early fall we wrote an obituary and picked a date to have someone from my mother’s church meet us all at the cemetery. It was the first time my three siblings and I had been together like that in a long time. Then some of us had an outdoor lunch together overlooking Marblehead Harbor. That experience gave me back some sense of control, that I didn’t have to give up my life to this virus. I felt like with that service I reassured myself that I had done my duty as a good daughter.

When I reflect on this past year, I think about things like going back to campus, and what it will be like to drive home and not go by to see her. I think about how some of our pre-pandemic habits will return, but not all of them will.

— As told to Manisha Aggarwal-Schifellite

Kathy Santoro is the director of HR Programs and Operations for the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.