Godzilla battles King Kong in “Godzilla vs. Kong.”

© 2021 Legendary and Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.

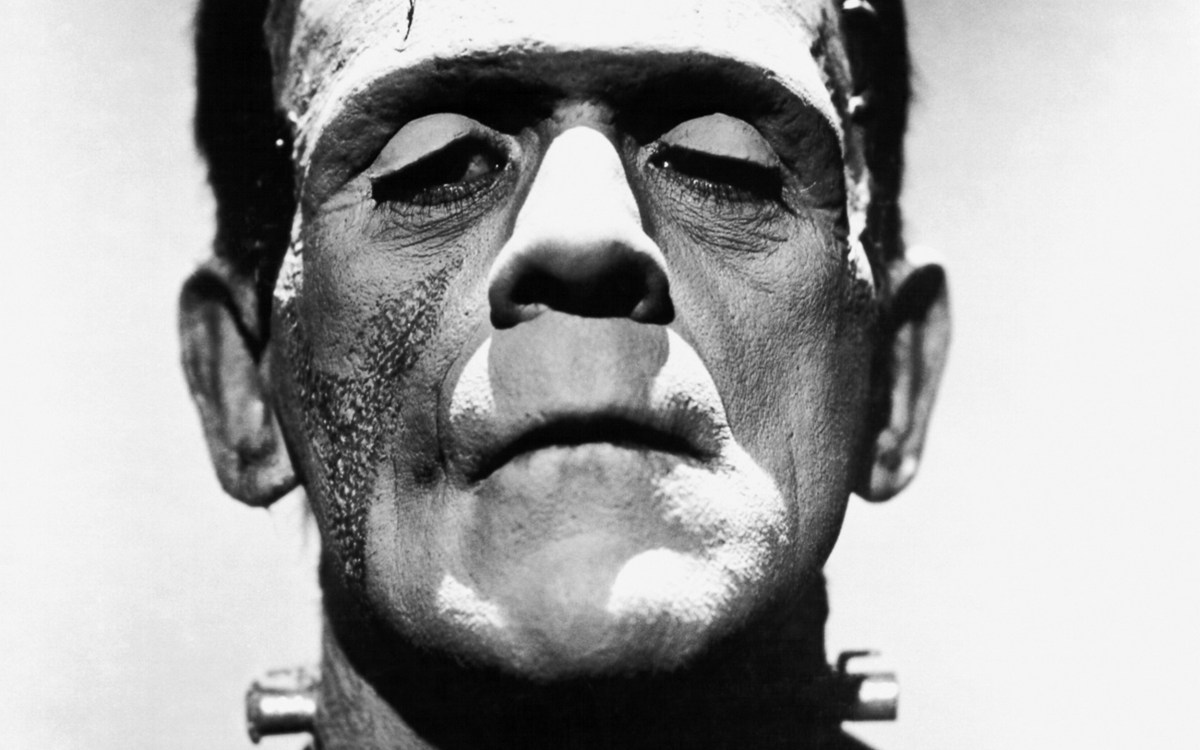

Round 2: ‘Godzilla vs. Kong’

Course looks at the history of monsters in Japanese culture as Hollywood cues up a reboot

Their last battle royale in 1962 earned the two adversaries an exalted spot in pop culture, so there is little surprise that interest in the upcoming rematch in the new film “Godzilla vs. Kong” is high. Aficionados of old-school Japanese kaiju, or monster, films are especially keen to see whether this bout between giant gorilla Kong and dinosaur-like sea monster Godzilla ends with a definitive winner. But that likely will be anybody’s guess, says William Tsutsui, the Edwin O. Reischauer Distinguished Professor of Japanese Studies and visiting professor of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, who has had a borderline fixation with the reptile armed with atomic breath since boyhood. His 2004 book, “Godzilla on My Mind,” provided an in-depth look at the character and its cultural impact. This semester, Tsutsui is teaching an East Asian studies course that explores the rich history of Japanese monsters, including the violent Godzilla. Tsutsui spoke to the Gazette about the 67-year-old brute and his course, and handicaps the fight.

Q&A

Bill Tsutsui

GAZETTE: What is the Godzilla story?

TSUTSUI: The franchise, by many accounts, is the longest-running film franchise in world history. It started in 1954 when the original film was released by Toho Studios. There have subsequently been 32 live-action films made in Japan and in Hollywood. That includes “Godzilla vs. Kong” [out Wednesday]. There were also three feature-length anime made in Japan.

There have been several origin stories over the years, but in the one that was established by the first movie, Godzilla was a dinosaur from the Jurassic period who lived in the depths of the Pacific Ocean that was then radiated by American H-bomb testing in the South Pacific. In the process, Godzilla became mutated and monstrous and radioactive. Of course, the core narrative in these films is that Godzilla then goes to Japan to attack Tokyo or other cities. The pattern that then developed, starting with “King Kong vs. Godzilla” in 1962, was pitting Godzilla against another monster that came from another island in the South Pacific or emerged from underneath the ocean or invaded from space. The movies are very formulaic: Godzilla fights the other monsters; they wrestle; they destroy a Japanese city or two; and then at the end, Godzilla usually wins and the world is safe again. It’s made for sequels. This has all led to Godzilla being one of the most well-known icons globally.

“My friends usually teased me about my Japanese heritage, but Godzilla was something we all thought was pretty cool.”

GAZETTE: Can you explain more of what Godzilla has symbolized, both in Japan in its early years and as it has changed over the years?

TSUTSUI: The original 1954 film “Gojira” was serious and somber. It had a pointed political message on the Cold War and the threat of nuclear apocalypse, and addressed Japan’s traumatic history of being the only place on earth where atomic weapons have been used. Over time, though, the movies lost that edge and evolved into more lighthearted entertainment aimed at children. Most Americans associate Godzilla with that later [iteration], with actors in rubber suits wrestling through toy cities. For many, Godzilla pictures, like spaghetti Westerns, became the ultimate B-movies. Of course, Godzilla also came to be closely associated with Japan in the global imagination. Godzilla was really a pioneer for Japanese pop culture coming to the United States. Giant monster films were the first form of Japanese mass entertainment to resonate with the American public and opened the doors for things that are now just part of daily life, like manga, anime, and even Hello Kitty.

GAZETTE: Godzilla has been the so-called “king of the monsters” for almost 70 years. How do you explain that staying power?

TSUTSUI: Godzilla got the title when the original 1954 film was brought to the United States by Hollywood distributors in 1956. That movie is famous because most of the political commentary from the original was edited out to make it more palatable to U.S. viewers. Some people have called this censorship, even white washing, but in the end, it was also just good business. The original film was almost certainly too critical of the United States, the atomic bombings, and nuclear testing to appeal to American audiences at the time. Unfortunately, a lot of great content, and the movie’s strong message, was lost in translation. Tagging Godzilla the “king of the monsters” was a reference to King Kong, who was riding a second wave of global popularity after the 1933 Hollywood film was rereleased internationally.

Why has Godzilla endured? Godzilla in many ways is an empty metaphor. That is to say, you can read into Godzilla what you want to read into Godzilla and that can change over time. The Japanese filmmakers were very skilled at adapting Godzilla to different moments and different audiences. For example, Godzilla goes from being a very dark and menacing presence — a threat to Japan in that first movie — to being a heroic figure and a protector for Japan. The issues that Godzilla touches on changed, too, from war memories and H-bomb testing in 1954, to things like pollution, political corruption, and remilitarization in later decades. When I wrote “Godzilla on My Mind” I asked for feedback from American Godzilla fans about why they love these movies so much. Almost to a person they said it’s because they are classic stories of good versus evil. They’re about a hero defeating bad guys, standing his ground, and winning.

“Back in 1962 when the original ‘King Kong vs. Godzilla’ came out, there was a legend that they made a Japanese version where Godzilla wins and an American version where Kong wins,” says William Tsutsui, the Edwin O. Reischauer Distinguished Professor of Japanese Studies.

Courtesy of William Tsutsui

GAZETTE: How did you get into the character?

TSUTSUI: I was 7 or 8 years old. I was in my parents’ bedroom on a blue shag carpet on a Saturday afternoon watching the “Creature Double Feature” on our big old Zenith TV set. A Godzilla movie came on, and I just fell in love. There wasn’t really a lot about Japan that I could relate to as a kid, growing up in a small town in central Texas. My friends usually teased me about my Japanese heritage, but Godzilla was something we all thought was pretty cool. So Godzilla ended up becoming an important part of my identity as a Japanese American, as something about Japan I could take pride in.

GAZETTE: You teach a course on Japanese monsters. What is it really about and why is it so popular?

TSUTSUI: It’s often been said Japan has more monsters than any other culture in the world. The course covers texts from the first written history of Japan, which is from the eighth century, up to the present day. We look at how monsters have figured in the Japanese imagination, and been shaped by social, political, economic, and technological change. Japanese monster culture is very vibrant — both in terms of its folklore and as new monsters (like Pokémon) are continuously being created. For the class, which touches on topics from “The Tale of Genji” to cryptozoology and UFOs, I thought I’d mostly have students who are interested in Japan, but there’s a really wide range of concentrations and personal experiences represented. What ties us together is our shared fascination with the variety and novelty of Japanese monsters.

More like this

GAZETTE: Last question, who do you think be the victor in this new film?

TSUTSUI: Back in 1962 when the original “King Kong vs. Godzilla” came out, there was a legend that they made a Japanese version where Godzilla wins and an American version where Kong wins. The reality is that the original movie was a draw. Basically, Kong swims off in one direction, and Godzilla swims off in another. The reason, of course, is that the studio wanted to make a sequel. That sequel never happened, so we’ve had to wait decades for a rematch. I am going to predict that this showdown ends up pretty much the same way as the previous one, without a definitive victor. What I’m hoping for, no matter who wins, is we’re going to have the opportunity to see two tremendous monsters, two real icons of global popular culture, just whomping on each other for 90 minutes. I have the sense that this is something we all need in this stressful moment of the pandemic. Fingers crossed, it’s not going to disappoint.

Interview was lightly edited for clarity and length.