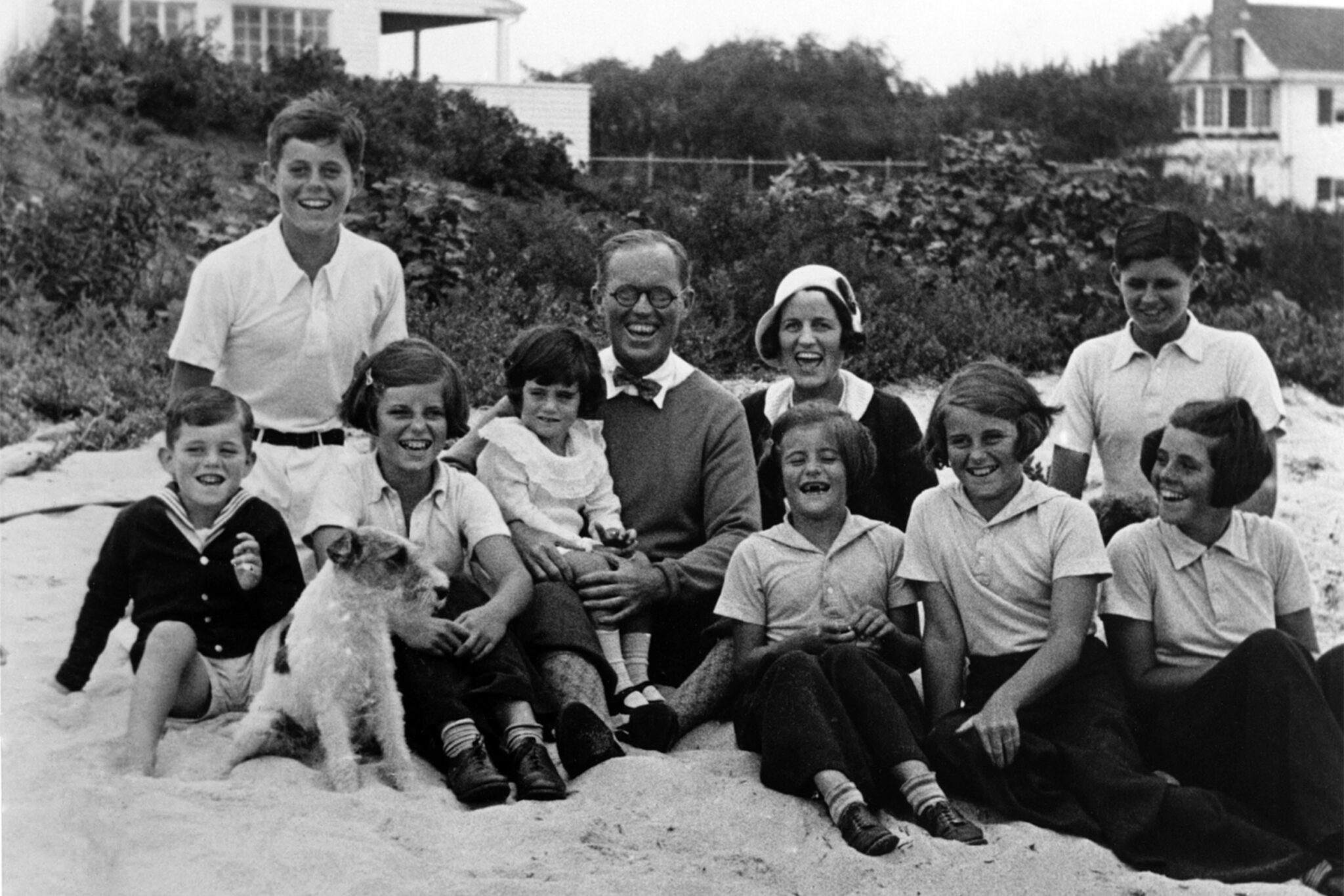

The Kennedy family at Hyannisport, Mass., 1931. Robert (from left), John, Eunice, Jean (on lap of) Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy (behind) Patricia, Kathleen, Joseph, and Rosemary.

Photo by Richard Sears, courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

On the road to JFK

New biography traces a burgeoning global view and progressive leanings

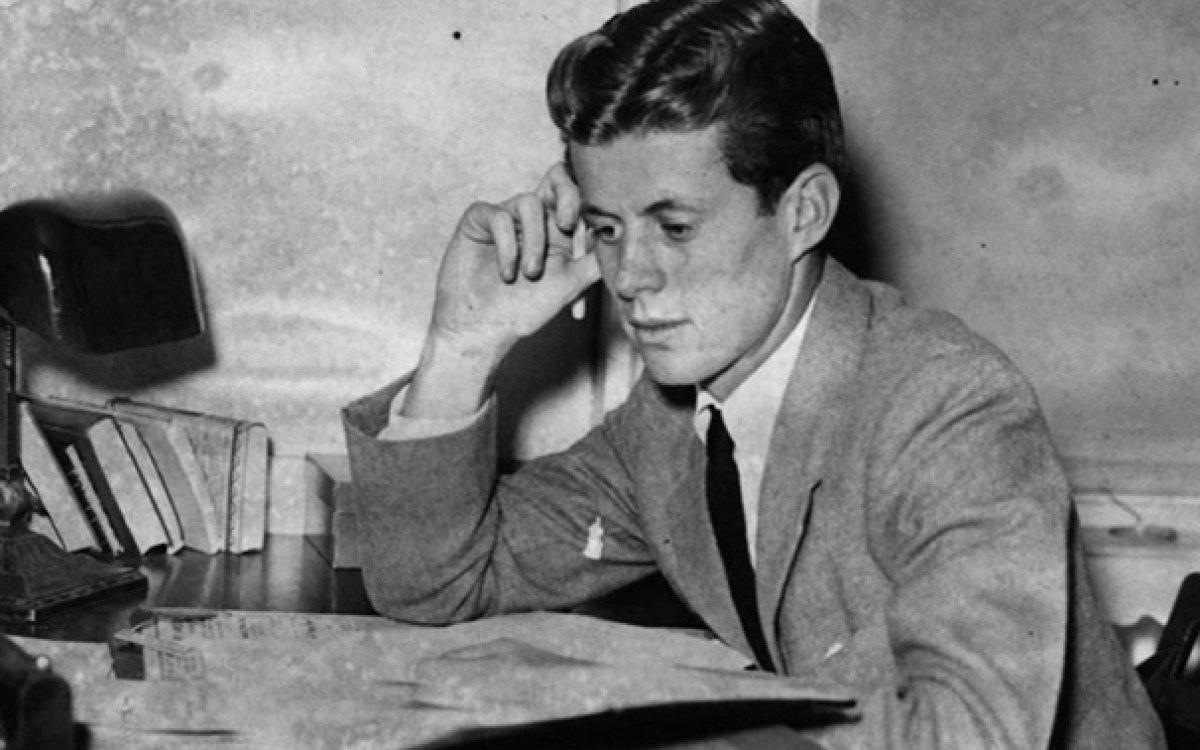

In his youth, John F. Kennedy took a more global — and, in some ways, a more progressive — approach than would be apparent until much later. That was only one of the revelations uncovered by historian Fredrik Logevall, whose recent book, “JFK: Coming of Age in the American Century, 1917‒1956,” covers the president’s early years.

Our 35th president “was a more serious student of history and international affairs at an earlier point than I thought,” said Logevall, Kennedy School professor of history and international relations. “I’d thought from previous books and my earliest research that he was frankly a bit of a slacker.”

In conversation Monday with fellow historian Jon Meacham in an online Institute of Politics Forum, Logevall discussed his findings and offered some hints as to what is to come in the second volume.

Kennedy’s early interest in a global approach was in stark contrast to his father’s noted isolationist stance, said the historian. Although Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. was a “towering figure” in his son’s life, the two differed early on. The elder Kennedy, who served as U.S. ambassador to the U.K. from 1938 through 1940, was “committed to appeasement,” said Logevall. “Right through Pearl Harbor, he thought we should make a deal with Hitler.”

“I’d thought from previous books and my earliest research that [John F. Kennedy] was frankly a bit of a slacker.”

Fredrik Logevall, author of “JFK: Coming of Age in the American Century, 1917‒1956”

His son disagreed. Growing up in the Great Depression and very aware of the threat of Nazi Germany and imperial Japan, “This is a young man who is thinking a lot about the challenges to democracy in ways that will continue throughout his life,” Logevall said.

Logevall credits the Kennedy matriarch, Rose, for nurturing this approach. In part, he noted, Kennedy’s bouts of illness as a youth made him more of a reader than many in his family, and, “Rose encouraged the bookish side of her son.” In addition, Logevall pointed out that the influence of professors at both Choate and Harvard as well as the young Kennedy’s extensive travels helped broaden his perspective.

“He spent several months in Europe, and this and other trips are of profound importance in terms of making him see a complete world, making him comfortable with a complex world in a way that his father never was,” said Logevall.

“I do give Joe the credit for allowing the kids to chart their own path,” he added. “Even though he had this powerful persona, he never insisted that they follow his views.”

Family connections did influence some of Kennedy’s other positions, however. Logevall explained the future president’s muted response to Sen. Joe McCarthy’s attacks on suspected Communists by pointing out that the Kennedy family had had a close relationship with the demagogic senator, and McCarthy even dated several of the Kennedy sisters.

“I do give Joe the credit for allowing the kids to chart their own path,” said Fredrik Logevall (bottom). Logevall was in conversation with Jon Meacham (upper right) and Institute of Politics Director Mark D. Gearan ’78.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

In addition, the historian noted, McCarthy remained popular with Irish Catholic voters even through his congressional censure in 1954. Still, “Had [Kennedy] not been in the hospital in late ’54, he would have voted for censure, I have no doubt,” said Logevall. “But the fact is, he didn’t indicate his position. He was being very careful.”

Kennedy also pulled back from other progressive views for political expediency, Logevall said. As a member of the House of Representatives from 1947 to 1953, Kennedy “had a solid, unexceptional voting record on housing and veterans’ affairs, anti-poverty legislation, and Civil Rights,” said Logevall. Once he was elected to the Senate in 1953, that changed. “In the Senate, he was really quite progressive.”

Once the White House came into view, however, everything changed. Looking to win support from conservative Southern Democrats, “You see JFK moving to the right to get that VP nomination,” said Logevall.

Looking ahead to the second volume of his biography, Logevall discussed how Kennedy would begin to shed that pragmatic conservativism once he won the presidency. That evolution was certainly encouraged by his brother Robert, Logevall said, a role he intends to address. “Robert needs to get his due.”

How progressive Kennedy would have become remains a matter of speculation, both historians agreed. Logevall, however, pointed out that the president was moving in that direction. Previewing his second volume, he cited the commencement address then-President Kennedy gave at American University in June 1963. In that speech, he looked forward to a time when “peace and freedom walk together. In too many of our cities today, the peace is not secure because freedom is incomplete.”

“It’s a very important speech,” said Logevall. “It made Civil Rights a moral issue.”

While so much remains unknowable, Logevall concluded, “I hope that people take away from the book that this is a consequential life” — not only because Kennedy was our president, but because of the times that he helped shape.

“He’s born in 1917 just as the U.S. is coming onto the world stage and dies in ’63 when the U.S. is this superpower of incomparable military and economic power,” said Logevall. “It is an extraordinary period in our nation’s history.”