Noah Harris ’22 is the president of Harvard College’s Undergraduate Council.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Working for change that’s both aspirational and real

Noah Harris ’22, new president of Undergraduate Council, plans to ’push what’s possible’

Noah Harris ’22 has never needed a clear path or an abundance of resources to make life better for those in his community.

“I come from Mississippi, which is one of the most charitable states and one of the poorest states. We have a culture of giving to a point where we don’t have things to give,” said the Hattiesburg native. “Having that in mind and gaining purpose in leading by serving others is what I try to do.”

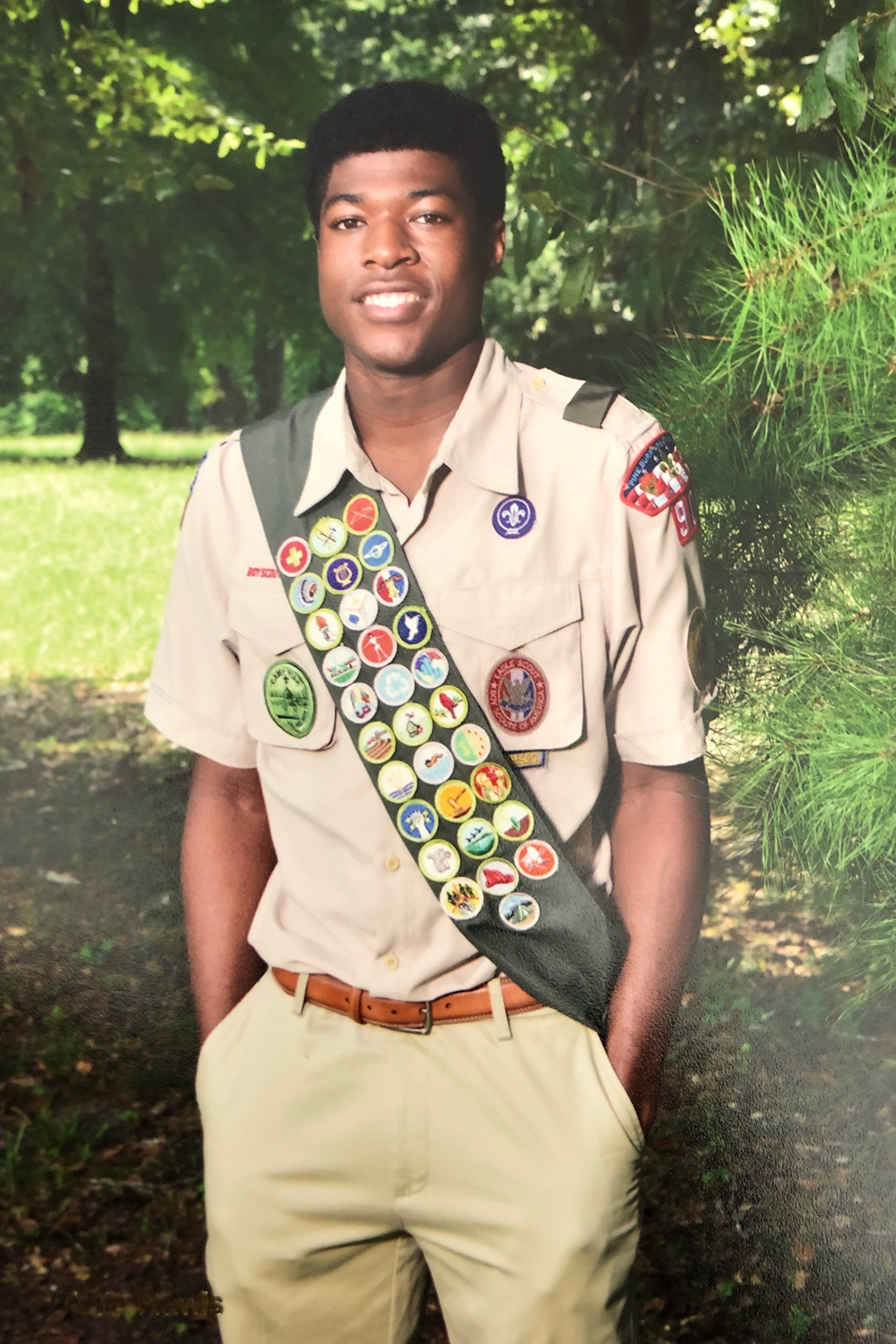

Sworn in last month as president of Harvard College’s Undergraduate Council (UC), Harris comes to the role with a record of service that started with his time as a Boy Scout (and later Eagle Scout) as well as being an avid athlete (baseball, basketball) and musician (violin, piano).

“I’ve always done a lot because there was so much I was passionate about,” said the Dunster House resident, who will live off campus in Somerville this semester. “I stayed with all of those things through middle and high school and always used those activities to make a difference.”

A government concentrator who served on the UC executive board this past year as treasurer, Harris is the first Black man to be elected president by the student body.

“I did my research, and I recognized the significance of things, but I didn’t run on the fact that it would be a historic win. I ran on the moment and having a great track record. It resonated, and the history came after that,” he said.

Harris shared the ticket with Jenny Gan, who earned the vice presidency, on a platform whose slogan was: Building Tomorrow’s Harvard. Their aim is to emphasize diversity and inclusion, especially in this time of racial reckoning and pandemic, and also to prioritize health and wellness “in a way it had never been before.”

When he was an Eagle Scout, Noah Harris said he stuck with it because he wanted to “make a difference.”

Courtesy of Noah Harris

The goal is to create “a campus all people can be proud of and call home,” he said. “We need to invest in resources so students have what they need. Having been in rooms with the administration, I know what’s possible and to push on that a little bit. I know where the limits are, and I try not to allow them to define what we do and to be innovative and creative. A lot of time at a school like Harvard there can be a sense of doing things the way they’ve been done. While that is not always a bad thing, students want to see more innovative improvements that make their lives better right now.”

As a first-year, Harris published “Successville,” a children’s book he wrote in high school about a teacher named Mrs. Jones and her plan for getting her easily distracted second-graders more engaged. Before the pandemic Harris toured elementary schools and libraries with his picture book to talk to kids about its central theme: how education, hard work, and stick-to-it-iveness are the keys to reaching your full potential.

“If we can get kids to learn that school is important, it will give them something to rally around,” he said. “I knew if I worked hard and got good grades that it would translate to a good college and good job. If we can be more present at the beginning in terms of goal setting and work ethic, we can get more kids many more options so when they have to make real decisions, they will have a larger skill set to go after what they want instead of settling for what’s safe.”

“A lot of time at a school like Harvard there can be a sense of doing things the way they’ve been done. … students want to see more innovative improvements that make their lives better right now.”

Noah Harris ’22, UC president

It’s a life philosophy that’s served Harris well but that doesn’t mean all of his efforts have worked out. He chooses, though, to see those as lessons and not simply failures. Case in point was his sophomore year partnership with Starship Technologies to try to bring delivery robots to campus. The goal was to get food to students who didn’t have enough time to return to their Houses for meals between classes.

“If you have a 10:30 in Northwest Labs and you also have a 1:30 p.m., but you live in Dunster, the only option is a cold bag lunch,” he said. “I saw an opportunity for automation and for opening access. We tested this white cooler-size robot at the oldest school in the country. Going into these old buildings — the visual was so funny.”

The College was receptive but jurisdiction issues over sidewalks with the city of Cambridge short-circuited the plan, he said.

“We had a lot of buy in and got pretty far, even into the mayor’s office. The city council was going to bring it to public discussion and then, a couple months later, the pandemic started,” Harris recalled. “People were very scared to pick up their food and prescriptions and packages then. It would have been very helpful.”

These days Harris’ UC work is focused on actions he hopes to take around sexual assault and prevention and social group accountability. As a member of the FAS Task Force of Signage and Culture, he has other goals.

“What I really want to do is make sure the people we celebrate on the walls and the buildings we name are who we are, not who we used to be,” he said. “I’m pushing the boundaries to have a campus that’s as antiracist as possible.”