Science Center Plaza on the Harvard campus.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

A safer return to campuses? There’s an app for that

COVIDU models the spread of COVID-19 in college settings

Colleges and universities are confronting a pressing question: How do they safely bring students back to campus amid a surging, world-wide pandemic? The decision involves careful consideration of a range of factors, from shared housing to testing capabilities to the likelihood of asymptomatic spread among students and staff. With death rates climbing to devastating levels and more contagious variants of the virus emerging, that choice has become even more consequential.

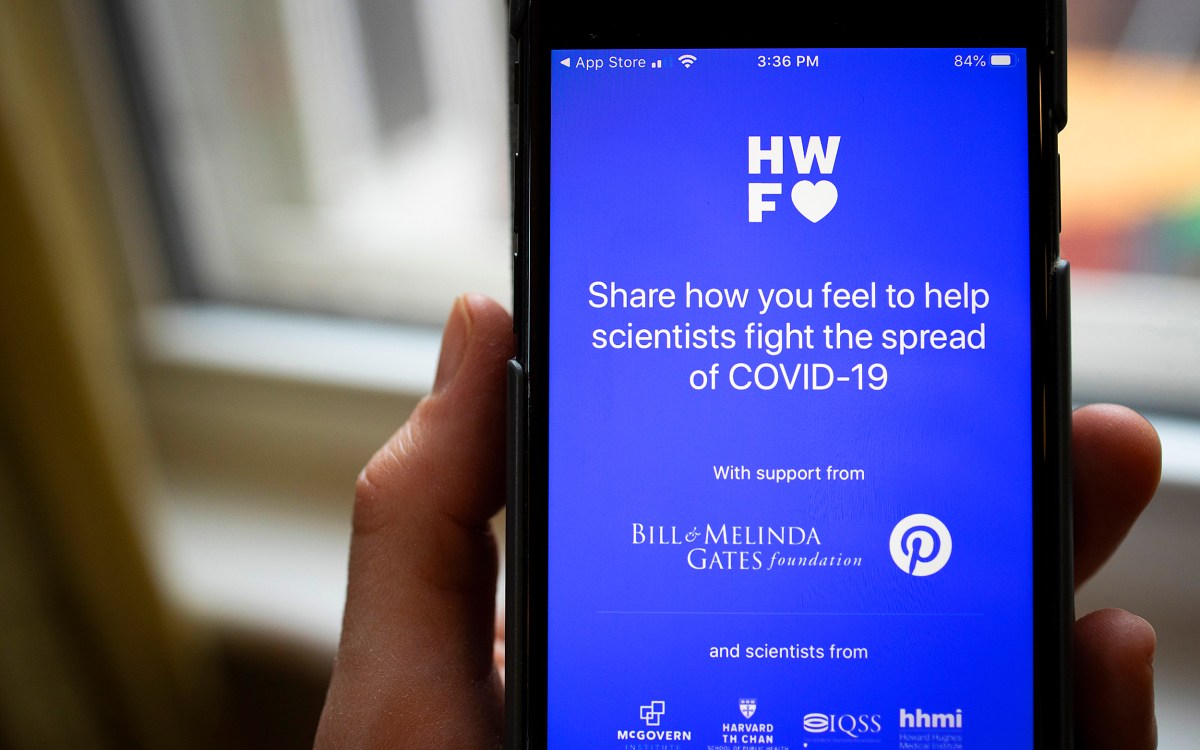

To help inform some of those decisions, a team of Harvard researchers that includes Gary King, the director of the Institute for Quantitative Social Science (IQSS), and Rochelle Walensky, the incoming director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, have launched a new disease-modeling app that simulates what different transmission and mitigation scenarios can look like in university settings.

Called COVIDU, the app is an interactive tool that factors several important conditions — community transmission, external infection, testing cadence, student population, and other social settings unique to campus communities — in modeling the spread of COVID-19 on a hypothetical campus and estimating the likelihood of different potential outcomes.

The easy-to-use tool allows users to fully customize the range of conditions on which the system bases its calculations. This helps to better mimic the users’ own campus community. It also considers the behavior of students and potential visitors, including how many might flout rules and attend social gatherings. The app even models super-spreader events and their fallout.

“The app essentially creates hypothetical people that would mirror what actually happens in the real world as closely as possible.”

Gary King

“It models how often do students interact with each other? How often might they just not follow exactly the public health recommendations? How often will we have a visitor from somewhere else that maybe shouldn’t be there? How often may somebody who’s helping undergraduates [like a staff member] come on campus with the disease and spread it to somebody else?” said King, the Albert J. Weatherhead III University Professor. “The app essentially creates hypothetical people that would mirror what actually happens in the real world as closely as possible.”

The app can also account for different epidemiological conditions in its predictions, like a surge in infections in the surrounding area or more aggressive mutations of the virus. For instance, Harvard administrators used the system recently to model how the new U.K. variant could impact the campus community.

The idea for the app came from the modeling work done by Harvard’s evidence-based decision-making subcommittee over the summer. Along with King and Walensky, who’s also chief of Massachusetts General Hospital’s Division of Infectious Diseases and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, the group included Christopher Avery, the Roy E. Larsen Professor of Public Policy at HKS; James Stock, the Harold Hitchings Burbank Professor of Political Economy in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences; and David Paltiel, professor of public health at Yale University.

Last summer, the subcommittee was tasked with amassing evidence and doing modeling and statistical analyses to inform decisions about bringing Harvard’s students back to campus for the fall and spring semesters. Working with IQSS, the group designed a system that combined classic epidemiological modeling with on-campus dynamics like shared housing, transmission rates in the surrounding community, student interactions, and a mass testing and isolation system. The system built on a similar COVID model for campuses that Walensky and Paltiel helped create earlier in the summer.

The researchers modeled the Harvard community with the new system and used it to come up with a recommendation for how many students could be brought back to campus and to decide the right level of testing to keep the community safe.

The COVIDU app expands that model and generalizes it so that other universities and organizations can use it. “You can set the parameters to reflect whatever conditions are appropriate to your campus or other campus-like environments, and then you can run the app and it’ll make any predictions from there,” said Zagreb Mukerjee, a research data scientist at the IQSS who helped design the system.

More like this

Users can also generate reports with graphs and tables on the scenarios they model and ones comparing different circumstances and consequences. The researchers hope the app will help improve understanding of COVID-19 transmission and mitigation strategies on college campuses, even among those without a background in modeling or epidemiology.

“By putting this out there, we’re hoping to get feedback from other scientists so that the underlying science can get better through collaboration. Of course, we also hope other campuses will benefit as well,” Mukerjee said.