The oddities of Inauguration Day

The two-month post-election wait used to be four, and a constitutional scholar thinks it should be shorter still

Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Herbert Hoover on their way to U.S. Capitol for Roosevelt’s inauguration, March 4, 1933. Choosing March 4 for the inauguration was “completely arbitrary,” said Sandy Levinson, a visiting scholar at Harvard Law School.

Library of Congress/Public Domain

More than two months. Ten weeks. Seventy-eight days.

That’s how long President-elect Joe Biden had to wait to be inaugurated.

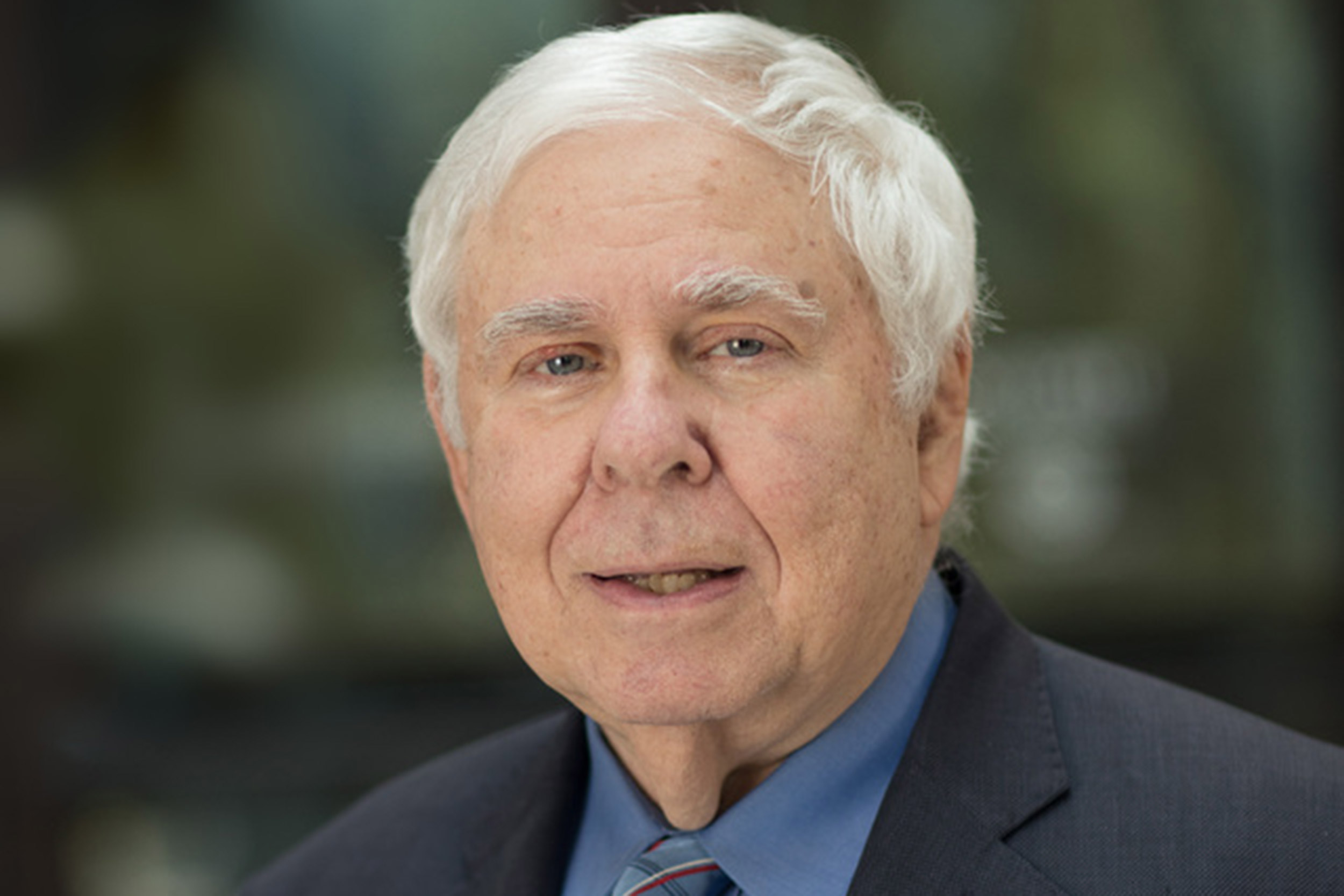

As mandated by the Constitution, Inauguration Day, when the formal transition of presidential power takes place, happens every four years on Jan. 20. To understand its long history, the Gazette interviewed constitutional authority Sandy Levinson, a visiting scholar at Harvard Law School last fall who teaches at the University of Texas at Austin Law School. Levinson outlined the first presidential inaugurations, how the transition was moved in the 1930s from March to January, and why he thinks it should happen even earlier.

Q&A

Sandy Levinson

GAZETTE: After the first inauguration of George Washington was held on was April 30, 1789, his second was held on March 4, 1793, and from that time on, March 4 was established as the official Inauguration Day. Can you explain why?

LEVINSON: It was completely arbitrary. March 4 was the date when officially the first Congress held its first meeting, and so that was taken as the zero point. April 30 happened also arbitrarily because it took that long, frankly, for people to get to New York from God knows where, by cart and the like. That’s how it was decided that March 4 would be the official date for the beginning and ending of terms. George Washington was a good sport. He didn’t say, “I get four years and four years should mean April 30.” He accepted March 4. And that’s how March 4 became Inauguration Day. It’s as simple as that.

The inauguration of President Abraham Lincoln on March 4, 1861. The 1861 inauguration is believed to be the first ever photographed.

Public Domain

GAZETTE: Why and when was Inauguration Day moved from March 4 to Jan. 20?

LEVINSON: What happened was one of my favorite amendments to the Constitution, which is the 20th Amendment, which is never taught and is not thought about. It’s regarded as dull and boring, a housekeeping amendment, but it’s important in two different ways. The first is that it illustrates that serious people were once interested in structural issues. In 1933, when we were in the middle of a worldwide depression, people realized that it was really dumb and dangerous to wait so long to inaugurate Franklin Roosevelt as the new president. They also did another thing that was very important. They moved up the date that Congress met to the very beginning of January. Until then, one of the craziest features of the Constitution is that a newly elected Congress did not meet for 13 months after the election. FDR, in fact, had to call a special session of Congress on March 4 when he was inaugurated because otherwise Congress would not have met until December of 1933. The 20th Amendment was quickly introduced and quickly ratified, and it’s very important because it moved Inauguration Day up to Jan. 20. But I think we should now realize, almost 90 years later, that Jan. 20 isn’t good enough. All of the dangers that were present by delaying inauguration to March 4 are now present from delaying it until Jan. 20.

GAZETTE: But March 4 was Inauguration Day for a long time. Although Congress proposed the 20th Amendment in 1932, it didn’t go into effect until 1937. How did the government function all those years?

LEVINSON: That’s an excellent question. I would turn it around slightly with another question: “Did the government work for all of those 139 years?” In 1860, for example, during the so-called secession winter, James Buchanan, who actually opposed secession, was president until March 4. Abraham Lincoln carefully said almost nothing of value between his election and his inauguration. In effect, we didn’t have a government. We had a legal president, and we had a president-elect, but that doesn’t add up to a government.

In 1932, the same thing could be said to be true. Franklin Roosevelt had beaten Herbert Hoover in November, but Hoover remained president until March 4. Hoover actually tried to get FDR to collaborate with him. FDR’s response was, “We only have one president, and you’re it.” Technically, that’s true. But frankly, for all of his abilities, Hoover was a failed president. Everybody was waiting for FDR to take over. And he didn’t do it until March. So again, the question is whether we had a government. One can say the very same thing about the time between Ronald Reagan’s defeat of Jimmy Carter in 1980. The fact that he didn’t take over until Jan. 20 is better than March 4, but we still had those 11 weeks during the Iranian hostage crisis, where one could genuinely wonder if we had a government. That’s why I think this is a really serious defect in the Constitution.

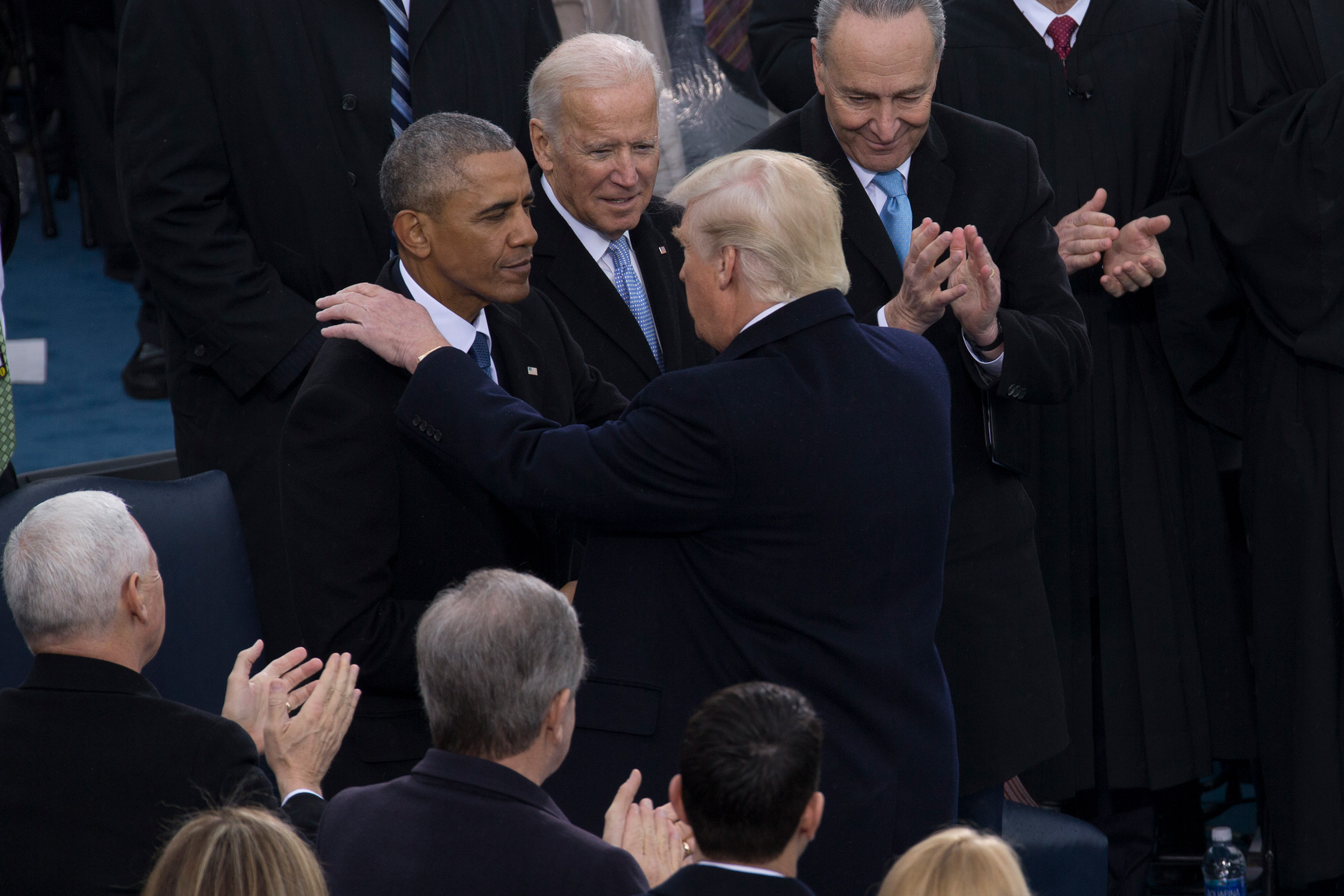

Ronald Reagan being sworn in as president on Jan. 20, 1981. President Donald Trump shakes hands with Barack Obama during the 58th presidential inauguration on Jan. 20, 2017.

Credit: White House Photographic Collection; U.S. Marine Corps Lance Cpl. Cristian L. Ricardo/Public Domain

GAZETTE: What is the role of the Electoral College in all of this?

LEVINSON: I would favor moving up inauguration to the Monday before Thanksgiving so all of us would have something to be thankful for. But the reason we can’t do that is the Electoral College, because everybody in the world now knows that we don’t elect our presidents on Election Day. All that Election Day does is to elect electors, and they don’t even meet until mid-December, and their votes aren’t counted until the beginning of January. This is crazy. We need to get rid of the Electoral College, but so long as we’ve got the Electoral College, then that inevitably structures when inauguration can take place. One could say why can’t inauguration take place the day after Congress certifies the president, which is on Jan. 6. The reason for that is that we have to look at the Electoral College as an overall system. This is a terrible system, and that’s why, in essence, it takes so long to inaugurate the winner.

GAZETTE: In terms of Inauguration Day, what do other countries do?

LEVINSON: I’d like to begin with the American states, in part because a lot of Americans say, “Who cares how they do it abroad? We’re exceptional. We’re America.” Well, America consists of 50 states, and you discover that no state takes as long to inaugurate its governors, and there’s one overwhelming explanation of that: No state elects its governors on the basis of an Electoral College. Hawaii and Alaska, the two newest states, inaugurate their governors on Dec. 1. Several states, such as New York and California, inaugurate their governors in early January. You look around the United States and you discover that no state uses anything like an Electoral College because no state thinks it’s helpful to wait so long to inaugurate its new governors.

Then you look abroad: The favorite example is the United Kingdom, where a newly elected prime minister takes office literally the day after election; it really is as simple as that. Sometimes there’s a deadlocked Parliament, or so-called hung Parliament, and there have to be some negotiations. But once the negotiations are resolved, the prime minister moves into Downing Street the next day, and it’s all over. In other parliamentary systems, it may take considerably longer. Belgium went literally a year and a half with no government because of negotiation problems. In presidential systems, which is really what we’re talking about, it’s very unusual. I think Taiwan takes a long time to inaugurate its president. Most countries don’t because frankly, at best, it’s unclear what the advantages are, and, at worst, it’s a clear danger.

GAZETTE: What are other drawbacks of holding Inauguration Day on Jan. 20?

LEVINSON: For me, it is a drawback that it adds to what I think is the dangerous tendency to turn the president into an elective monarch. That is to say, we vote for presidents having only the vaguest idea of whom they might actually appoint to the government. In parliamentary systems, parties run with cabinets; you don’t merely vote for a prime minister, you generally vote for a shadow government. We, I think, carry that to an exaggerated degree. Americans have created the whole myth of “the transition,” in which the newly elected president announces, often with quite a bit of surprise, who the new secretary of state will be, and who the new attorney general will be, and so on. Frankly, I’d like to know when I vote for them, because the president, however important, is to some extent the Wizard of Oz. Real policies and real decisions are often going to be made by the secretary of the treasury, the secretary of state, and the attorney general.

But we build up the president into this truly mythic figure, and I would like to see us demystify the presidency. This long hiatus just adds to the excessive focus we put on this one person, including Joe Biden. I think Biden’s cabinet’s perfectly all right, but I would have liked to have known in advance who the key appointments would be. I think that is also part of the problem.

“I think we should now realize, almost 90 years later, that Jan. 20 isn’t good enough. All of the dangers that were present by delaying inauguration to March 4 are now present from delaying it until Jan. 20,” said Sandy Levinson.

Courtesy of Sandy Levinson

GAZETTE: How have the events of Jan. 6, when Trump supporters took over the Capitol, affected your view of Inauguration Day?

LEVINSON: The basic problem is that Donald Trump continued to be president with every iota of presidential power and legal authority until Jan. 20. In other interviews, I have talked about my desire for a no-confidence vote, but we don’t have that in the United States. Until he’s out of office, he is a clear and present danger; he’s a menace. Jan. 6 just proved that; he basically instigated an insurrection. In any normal political system around the world, he would be out, but not here.

GAZETTE: How do you envision that Inauguration Day could be moved to an earlier date? Could this happen without touching the Electoral College?

LEVINSON: Inauguration Day could be moved up a week or two, maybe, but the Electoral College is the elephant in the room. We need to get rid of it. Unfortunately, that can be done only by constitutional amendment, but it’s very difficult to amend the Constitution: Article 5 outlines how amendments can be made. The quick answer to the question of why we still have the Electoral College is because of Article Five.

But I think there are two answers to how to tackle the Electoral College issue. One is to amend the Constitution and amend it tomorrow. Is it possible? Probably not. Here you run into the true awfulness of Article Five. I taught a reading course at Harvard Law School in the fall called “Reforming the American Constitution. Is it desirable? / Is it possible?” My answer, of course, is that it’s highly desirable, but I’m really pessimistic as to whether it’s truly possible. Because Article Five is an iron cage, a handcuff, whatever the metaphor you want to use about it is probably accurate. There is nothing good about Article Five. One can’t say it’s unconstitutional because it’s a very important part of the Constitution.

The more optimistic argument is that people have to mobilize, not engage in insurrection. They do have to mobilize, including making the lives of their representatives and senators uncomfortable by showing up at town meetings and saying that it is time to get rid of the Electoral College. By getting rid of the Electoral College, we can also get rid of this ridiculous hiatus between election and inauguration. But that could only happen if an aroused public light fires under the feet of representatives and senators who have this ridiculous veneration for the United States Constitution. We heard all these speeches in Congress last Wednesday about the wonders of our framers and the glory of our Constitution. That’s where I am most contrarian. I don’t bash the framers of it. I think they did a fine job for 1787. It is the senators and representatives who should be ashamed of themselves for not learning the lesson of the 20th Amendment, which is that you can really think and do something about structural problems. And we don’t.

This article was lightly edited for clarity and brevity.