A crowd gathers along 16th Street in front of the White House on Saturday to celebrate the presidential race being called in favor of President-elect Joe Biden.

AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais

Dust is starting to settle after election, yet the way forward is unclear

How much change is possible? In handling of pandemic? Economy? Health care? Equity?

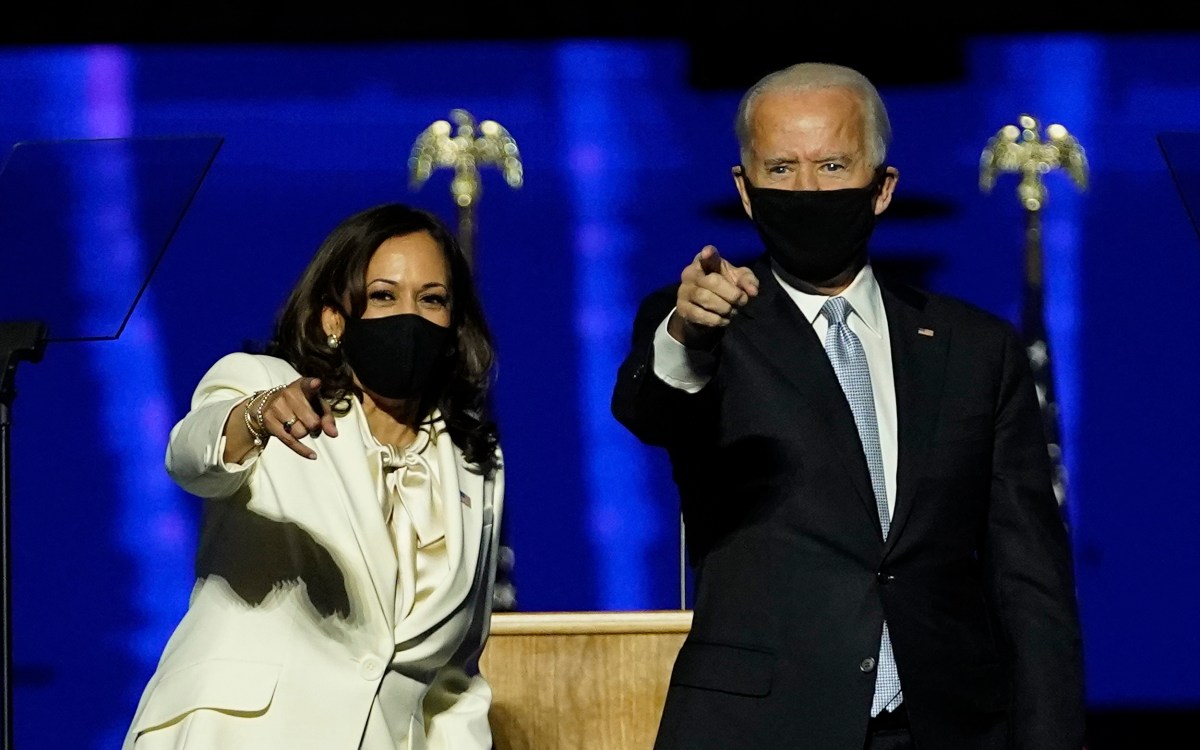

The street parties and protests across the nation ignited on Saturday by the presidential election results have quieted, for now. President Trump and the vast majority of Republican political leaders have steadfastly refused to concede, with some vowing to pursue congressional investigations of the balloting and a notable few like, former President George W. Bush and Utah Sen. Mitt Romney, offering their congratulations to President-elect Joe Biden and Vice President-elect Kamala Harris. The Democrats, meanwhile, are moving quickly to set up transition teams in key areas, announcing a coronavirus task force, mulling potential candidates for cabinet posts, and taking a hard look at regulatory and other changes they want to and can make unilaterally, virtually upon taking office. The dust is beginning to settle, but much is still unclear. The Gazette turns once again to scholars and analysts across in the University to get their views of what happened and what comes next.

The sidewalks of Harvard Square filled on Saturday with people carrying signs of support for President-elect Joe Biden and Vice President-elect Kamala Harris.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

On the first woman vice president

What are your thoughts on the historic selection of a Black and Indian American woman?

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Harvard University

Maya Jasanoff

X.D. and Nancy Yang Professor, Coolidge Professor of History, and Harvard College Professor

History books will register Kamala Harris as a “first” on many fronts, and I’m very pleased by all of them. As a historian, I’ll note that “firsts” usually have forerunners. Coming more than 30 years after the first woman appeared on a major party’s national ticket, Harris’ election feels, if anything, overdue. And the historical significance of “firsts” may depend, in turn, on what follows, as Harris graciously acknowledged when she said, in her victory speech, that “while I may be the first woman in this office, I won’t be the last. Because every little girl watching tonight sees that this is a country of possibilities.”

Many will see Harris, the first Black vice president, as a figure ideally situated to advance the urgent work of racial justice. But I also hope that her own mixed and immigrant heritage — half-Indian, half-Jamaican, and all-American — will bring nuance and depth to the national conversation about identity and belonging. In every election cycle, for instance, we hear pollsters and pundits slicing the electorate into demographic blocks that can end up reifying racial and ethnic categories in ways that are neither constructive nor especially accurate. It was only two decades ago that the Census Bureau started allowing people to place themselves in more than one racial category.

On a personal note, as the daughter of an Indian immigrant mother — and granddaughter of a woman named Kamala — I hope that Harris’ prominence will raise Americans’ basic cultural and geographical awareness about the Indian subcontinent. I’ll welcome a time when more Americans know that Hindi is a language, while Hindu is a religious affiliation; that India is in South Asia, not “Southeast” Asia; and that Indian food can be “spicy” (as in, flavorful) without being inedibly “hot.” Most of all, after the last four years of chaos and division, I am delighted to see a person in this role who understands what America is and might yet be, from perspectives no vice president has had before.

First takes

What can we take away from the results of this election?

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Harvard University

James T. Kloppenberg

Charles Warren Professor of American History

We should remember that almost half the electorate voted for a man whom serious scholars consider the worst president in U.S. history. That fact should sober those of us who expected a Big Blue Wave to bring sweeping progressive change. Instead the election reminds us how deeply divided our nation is. The anguish we progressives felt four years ago now darkens sections of the U.S. that voted as heavily for Trump in 2020 as Massachusetts and California voted for Biden.

If we keep telling ourselves that we see the world clearly while our opponents are blind, we will continue to antagonize voters we need. Partisans of equality will never persuade plutocrats or racists to change their tune. But instead of wondering why nearly half the nation preferred a lying, self-dealing con man to a decent, empathetic moderate, we must try to respect the different perspectives and genuine grievances of people whose lives and convictions many progressives have denigrated and dismissed for decades.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Harvard University News Office

Daniel Carpenter

Allie S. Freed Professor of Government

Generally, the results to date have shown a system of election administration that is more robust than many had feared. There were concerns about foreign interference, suppression of turnout through voter intimidation and postal delays, and massive court interference with balloting. All of those are serious concerns, and we still need stronger judicial deference to the republican principle of popular majorities. Yet massive turnout happened anyway, in part because people across the spectrum wanted their votes counted and because hundreds of thousands of volunteers and civil servants worked diligently to uphold the rule of law.

That’s some good news, but there is bad news to go with it. The crisis we are in is not merely polarization but a world of what you might call “alternative reality factions,” and it is a phenomenon that is especially accentuated on the far right. The birthers of 12 years ago have become the #StoptheSteal crowd today. In 2008, they contested the election of President Barack Obama not on the basis of numbers, but on the basis of his identity and eligibility.

In 2020, in a closer but still decisive victory for President-elect Biden, they are now questioning not even late-arriving ballots but the fact that fully legal, on-time ballots were counted after Nov. 3. Votes have been tallied well after Election Day for over a century in our country. The common element to these alternative realities of birtherism and stolen elections is, unsurprisingly, racism. The #StoptheSteal faction has focused its ire upon vote aggregation in cities, especially those dominated by Black people and other people of color.

The rejection of Trump is an important moment. The difficulty is that Trump’s caustic brand of white-resentment politics brought a lot of Republicans to the polls in 2020 and benefited a number of down-ballot Republicans in the House and Senate races as well as at the state level. There will be a durable incentive for Republican candidates to recreate and harness that energy, and if Trump is eligible in 2024 he might try to run again.

Sandy Levinson

Visiting Professor of Law at Harvard Law School

The election of Joe Biden certainly means that a majority of the electorate has had it with Donald Trump. That being said, one should acknowledge that Biden’s “coattails” were minimal. Although we won’t know for sure about control of the Senate until the two Georgia runoffs in January, it would be near-miraculous if Georgia fired both of its incumbent Republican senators in favor of distinctly more liberal Democrats. So we should assume that once again we will be faced with a “divided government,” where Republicans in the Senate will be able to stymie most legislative programs passed by the House and supported by the president.

And Republicans will have the power to do that only because of the scandalously undemocratic (and not only un-Democratic) reality of the U.S. Senate, which allocates equal voting power to Wyoming and California, Vermont and Texas. President Biden, like his immediate predecessors, will draw on all of his purported executive powers. That will not be good for the country inasmuch as it will only further confirm the reality of a truly dysfunctional Congress and exaggerated hopes placed in presidents who, even if they are not authoritarians, feel compelled to push the envelope of what might be described as near-dictatorial powers.

I continue to believe that the country very much needs a new constitutional convention capable of addressing the adequacy of our present arrangements with the “reflection and choice” praised by Alexander Hamilton in Federalist 1. For me, the Constitution is certainly as much the cause of our problems as the potential solution. Unfortunately, it has been years since we have had political leaders willing to acknowledge the need for constitutional reform.

It may, therefore, be whistling past the graveyard to exhibit much genuine optimism about the prospects for a successful Biden presidency save for the fact that he is at the other end of the spectrum in terms of basic decency, empathy, and concern for the American public than the man he will replace. (But remember that Trump, thanks to the Constitution, will remain in office, with all of his malign character and rage, for two more very long months, until Jan. 20, 2021, another aspect of our system that might well be addressed by a constitutional convention.) I share the sense of elation and hope that our national nightmare is drawing to an end. But inasmuch as I believe that our nightmare is in part the result of a truly defective constitutional system, I fear that we might be hoping for too much.

What might a Biden agenda look like? In what areas can we expect him to lead?

KLOPPENBERG: The history of democracy shows that it must rest on cultural commitments to deliberation, pluralism, and reciprocity. Willingness to allow the winner of an election to govern, even if the winner is one’s worst enemy, rests on a reservoir of trust, which has been receding in the U.S. since the 1990s.

If Democrats win both Georgia Senate seats in January, President Biden can push an agenda as progressive as conservative Democratic legislators will allow. If not, he will be forced to follow his coalition-building instincts. If he proves no more successful than Barack Obama was, we face four more years of government by executive order rather than legislative compromise. That formula guarantees accelerating polarization.

For decades, three-quarters of the public has preferred incremental problem-solving to the most ambitious policies proposed by activists on the ends of the political spectrum. Unless both parties surrender some currently non-negotiable demands in order to find common ground, the continuing stalemate will prevent progress toward dealing with the pandemic, the climate crisis, or rampaging inequality.

CARPENTER: Especially on the pandemic, I suspect President-elect Biden will focus his efforts on the issue and not ignore it. He will defer to scientists, academics, and industry in setting policy. He is likely to have the nation rejoin the Paris Agreement to fight climate change. Important changes will also occur in the management of the federal government.

Politically, and whether or not the Democrats retake the Senate, Biden will likely reach out to moderate and amenable Republicans such as Sens. Mitt Romney, Lisa Murkowski, and Susan Collins, and possibly Pat Toomey and Rob Portman as well. Cooperation with those Republicans may be crucial to his presidency.

But I think one of the most important areas of leadership will come in daily behavior or the set of things President-elect Biden will not do: He will not send angry tweets on a daily basis, not fire off inflammatory missives, and not hold rallies. He will try to return the country to a sense of calm by modeling calmness in his person. I dearly hope he succeeds, but there are strong winds pushing in the other direction.

On the economy

What does a Biden win mean for the economy, especially in regard to COVID, and what’s likely to change going forward and how?

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Harvard University

James Stock

Harold Hitchings Burbank Professor of Political Economy

A useful way to think about the medium-term economic outlook is that there is an unprecedented part — before we have a widely adopted vaccine — followed by a normal part. Over the past three decades, normal recoveries have been slow, with the unemployment rate falling by about 0.7 percentage points per year. This slow speed largely stems from everyday dynamics in which it simply takes time for people to find jobs (especially if they have been out of work for a long time), for firms to grow, for demand to expand, and for people to move for new opportunities. So the strength of the economy two or three years from now hinges critically on where we start that normal recovery, which in turn depends on what happens between now and when a vaccine is widely adopted.

I believe a strong prevaccine recovery is possible, but whether that happens depends more on the Biden administration’s success on public health policy — and in working with Congress — than on traditional economic policy actions it might take.

The economy has come a long way from the depths of March, April, and May. Some sectors, such as information technology and residential construction, are doing as well or better than before the virus hit. But sectors that rely on in-person activity remain far below normal levels. A large body of post-March economic research indicates that this contraction is largely the result of self-protective behavior, not government lockdown orders. Moreover, many school districts have chosen remote or hybrid learning, making it hard or impossible for some parents to continue working or to return to work.

Thus, the first economic task facing the Biden administration is a public health task: getting the prevaccine pandemic under control. Some of this work, like depoliticizing masks and providing credible guidelines supporting safe school reopening, can be undertaken administratively. Having rapid, widely available, cheap or free coronavirus screening testing with a low false-positive rate, combined with providing support for self-isolation, is within reach and could be highly effective in supporting a prevaccine recovery, but would require congressional cooperation.

The recovery so far has benefited from massive federal fiscal support. Plausibly, the hopes for that support continuing will be less if the Senate remains under Republican control than under a single-party scenario. Moreover, there isn’t much more that the Fed can do. So on horizons both of months and years, our economic health depends on the Biden administration’s success in public health.

Health care

What do you see being the most likely shift in health care policy under a Biden administration?

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Harvard University

Benjamin Sommers

Huntley Quelch Professor of Health Care Economics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Professor of Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School

The big question is what happens to control of the Senate. If Republicans maintain control, Biden will mostly be pursuing changes through executive orders, regulations, and oversight. This means likely reversing Trump policies like work requirements in Medicaid and rules aimed at keeping legal immigrants from participation in certain public programs, restoring funding for family planning services, and encouraging states that want to pursue progressive policies to shore up coverage and access to care. If Democrats regain the Senate, which it looks like they might depending on the Georgia runoffs, then the door opens to legislative changes like a public option or Medicare buy-in, bolstering subsidies in the ACA [Affordable Care Act] marketplaces, and sending more federal funds to support state Medicaid programs during the recession.

With respect to COVID, I expect we will see a much more hands-on approach from the Biden White House, working closely with states and federal scientists at the CDC to develop more consistent guidelines on a host of issues — masks, reopening policies, school safety, and more. They’ll certainly continue to watch vaccine development closely and getting large-scale public trust for that will be key. Whether or not they can also pass additional emergency relief to health care providers, schools, and state/local public health agencies will depend on whether the Senate is willing to cooperate.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photogra

David Cutler

More like this

Otto Eckstein Professor of Applied Economics

There will be many. To start, there will be a shift from undercutting the Affordable Care Act to enhancing it. That will show up in many guises, likely not legislation (if the Republicans control the Senate), but in other ways.

In the fight against COVID, the power of the president is limited, but the example is really important. Biden will push for masks, testing, tracing, etc. If a new COVID agreement is not reached in Congress before Jan. 20, Biden will need to take that up as well. Even before Jan. 20, Dems will look to him for advice.

If you were advising the new president — any new president — what would be your No. 1 priority for change?

CUTLER: In my opinion, the single most important economic issue facing the country is that a large share of the population feels like it has been left behind economically. The new president will need to deal with that. There is not one single policy or piece of legislation that will address it. It will require hard work at many levels and throughout the government and private sectors. But it must be addressed.

— Alvin Powell, Juan Silezar, Liz Mineo, and Manisha Aggarwal-Schifellite