The Peabody Museum’s “Contested West” exhibition featured a threshold by tribal educator/co-curator Butch Thunder Hawk (Hunkpapa Lakota)

Photo by Mark Craig

Museums of Native culture wrestle with decolonizing

Focus turns from collections to communities, more inclusive and complex histories

Growing up in Maine as a member of the Passamaquoddy Tribe, Chris Newell used to visit the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor, which showcases the history and culture of the Native peoples of Maine. But he remembers being struck by the way the institution told the story of his community.

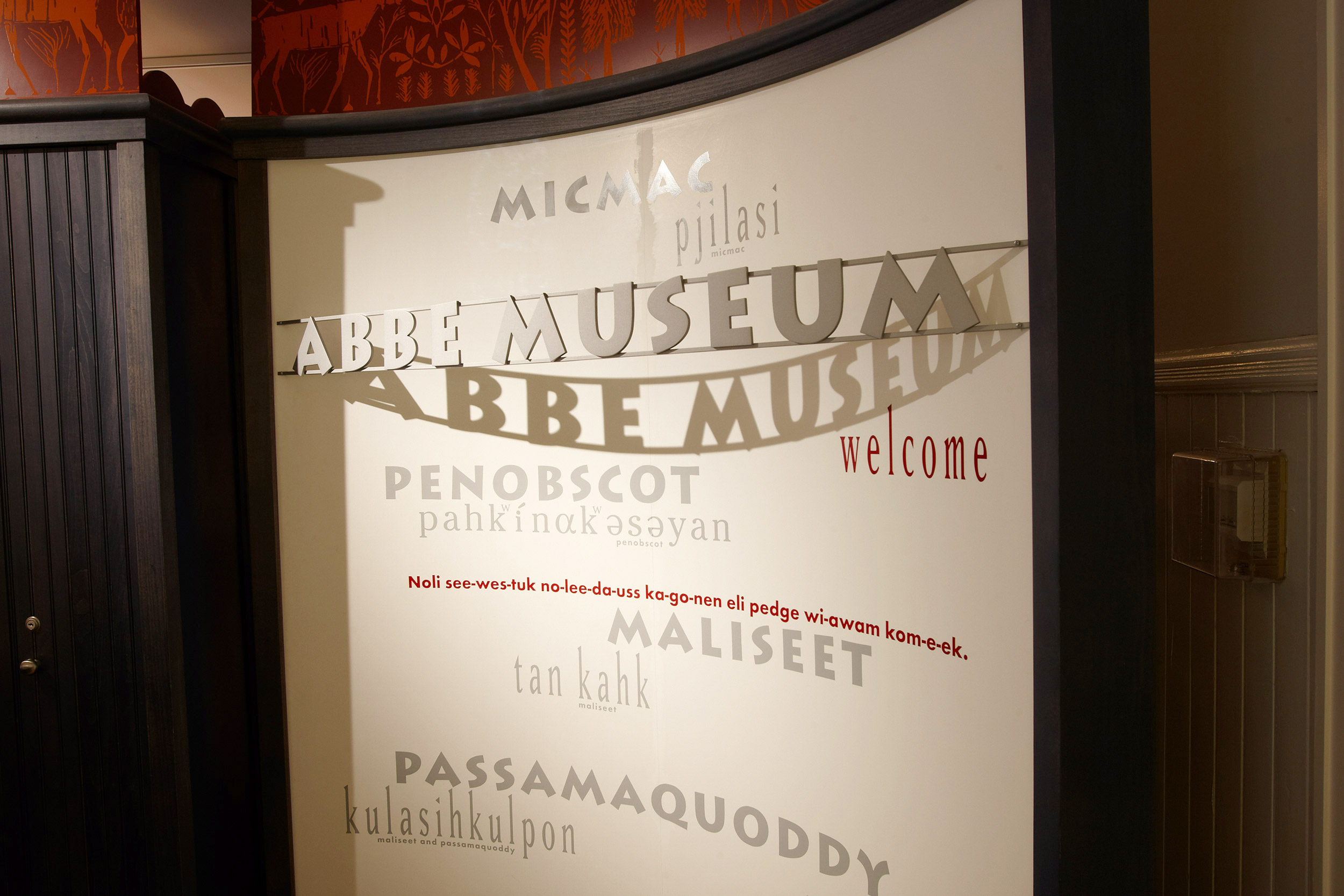

“As a young Native person walking into that museum, I can you tell you that the voice of the museum would speak to me, a Passamaquoddy child, as if I didn’t exist,” said Newell, who in February became the first member of the Wabanaki Nations, which comprises the Maliseet, Micmac, Penobscot, and Passamaquoddy, to run the 94-year-old Abbe. “That’s an experience I don’t want my children to have. I want the living Native voices of our peoples to be there as well.”

A leading advocate for decolonizing museums, Newell spoke at a Wednesday discussion, “Reimagining Museums: Disruption and Change,” presented by the Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology in collaboration with the Harvard University Native American Program, and the Harvard Museums of Science & Culture.

Museums have long been colonial institutions, but over the past decade, academics and activists have called for them to change their practices, embrace a more inclusive, honest, and morally complex narrative of history, and become agents of social justice. The calls have become stronger and more urgent amid a national reckoning over race and a racial justice movement, said Castle McLaughlin, Museum Curator of North American Ethnography at the Peabody Museum, who moderated the event.

Panelists stressed the importance for museums to undo their legacy and the narratives most of them still use in telling the stories of Indigenous people as if they are “a thing of the past,” which contributes to the dehumanization of Native peoples and helps render them both voiceless and invisible.

“As a young Native person walking into that museum, I can you tell you that the voice of the museum would speak to me, a Passamaquoddy child, as if I didn’t exist.”

Chris Newell

The Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor, Maine.

Lorén Spears, a member of the Narragansett Nation and the executive director of the Tomaquag Museum in Rhode Island, spoke of how European and American colonization, driven by greed and entitlement, led to museums becoming places to “preserve the past” and play the role of gatekeepers, choosing which stories to tell and how they were going to be told. In many cases, Spears said, museums embedded in Euro-centric values told stories that were inaccurate, perpetuated misconceptions and stereotypes about Native cultures, and lacked Indigenous voices.

At the Tomaquag museum, Rhode Island’s only Indigenous museum, exhibits are presented from a first-person perspective and don’t follow a linear timeline to stress the fact that Indigenous people are still present in the lands they and their forebears have occupied for centuries. “We didn’t just die off in 1675,” said Spears. “We’ve been here all along.”

But the effort to create equity in representation within museums and give voice to communities to tell their own stories is hard, said Spears. “I’ve even had people come to me saying, ‘Oh, you’re rewriting history,’” she said. “No, we’re not rewriting history. We’re including the history that was already there but that has been erased in the sanitized history we were given.”

This year’s racial and social justice movements make Spears and Native activists feel hopeful. Many have been invited to join the boards of cultural institutions to make them more inclusive and representative.

At the Peabody, founded in 1866 with a mandate to chronicle the cultural history of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, efforts to rethink the role of the museum are already in place under the concept of “ethical stewardship.”

“We are stewarding collections rather than owning collections,” said Jane Pickering, William and Muriel Seabury Howells Director of the Peabody Museum, during the panel. “And we’re making that idea foundational to everything that we do both behind the scenes and in our galleries and programs. We are intentionally trying to recognize the rights of all the heritage stakeholders, descendant communities, indigenous communities, and building relationships with communities.”

“We are stewarding collections rather than owning collections.”

Jane Pickering, director of the Peabody Museum

As part of that effort, the Peabody Museum recently launched the virtual exhibit “Listening to Wampanoag Voices: Beyond 1620,” in which tribal members reflect on collections spanning the 17th to 20th centuries at the institution.

Pickering also talked about the colonial legacy of the Peabody and how it is trying to transform itself to respond to demands for equity and inclusion.

“It’s really a time of profound change for all museums, as we grapple with being colonial institutions,” said Pickering. “We’ve benefited enormously from imperialist and colonial activities. We can see that colonialism has driven what was collected, how we collected, the language we use in our database to document collections of past exhibitions, and how collections were used in teaching.”

Pickering noted that tribal museums such as the Abbe and the Tomaquag represent an inspiration to other institutions as they fundamentally rethink their purpose and adopt a change of focus from collections to communities.

The value of a tribal museum is that it’s “unapologetically Native,” said Newell, and offers a “home within a home” to Native peoples in Maine. But other museums need to update their 19th-century model to help empower Indigenous communities and ensure the well-being of all citizens.

“What I always tell people is that no matter what happened in history, as hard as some of it is, it is how we got here,” said Newell. “If we do not learn those lessons, we’re not going to do well going forward. We’re all here now, and we all have to figure out how to steward this land, especially in the state of Maine. We’ve got to learn how to steward that land together so that it’s sustainable, so we’re here for the next 12,000 years.”