Democratic vice presidential candidate Sen. Kamala Harris will debate Vice President Mike Pence on Wednesday.

AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster

American voters don’t hate ambitious women, after all

Study finds some differences in attitude, though, depending on party

Hillary Clinton’s surprising loss in the 2016 presidential election was chalked up, in part, to a widely held belief that voters prefer male candidates generally, and that they are especially put off by women who appear too ambitious or aggressive.

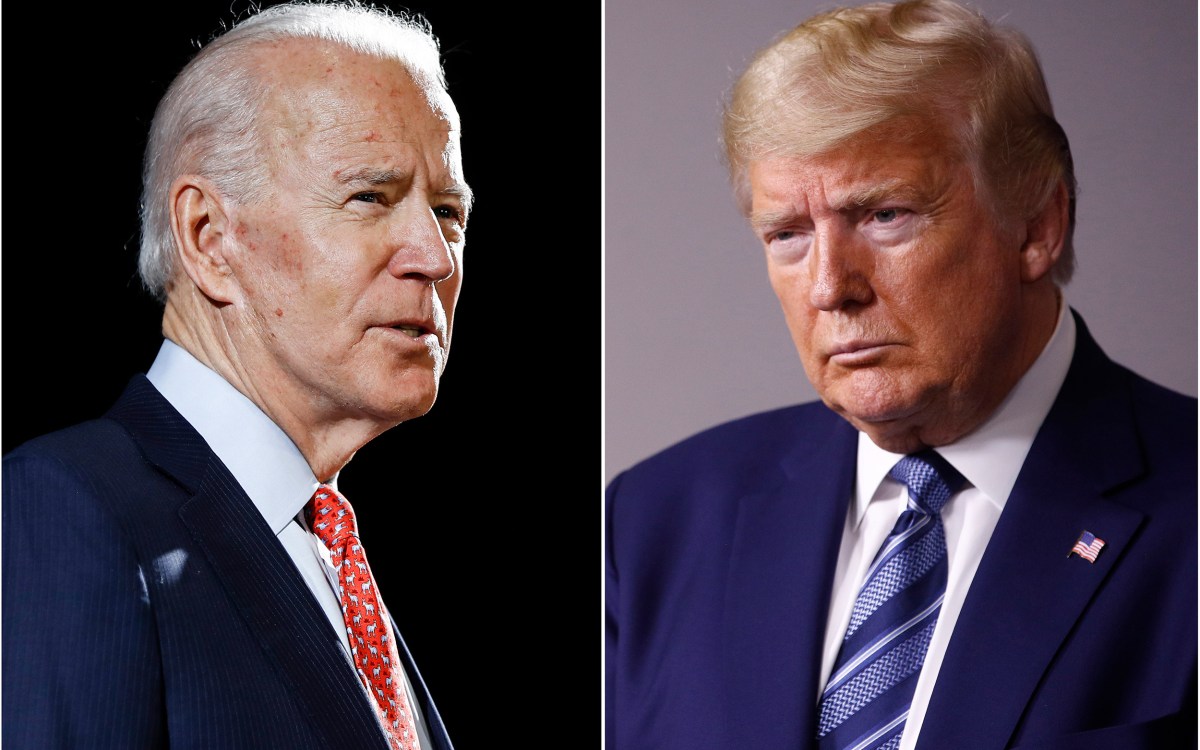

Those concerns have been revisited by pundits, in workplaces, and across dinner tables with former Vice President Joe Biden’s choice of U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris as his running mate on the Democratic ticket. Some critics have called the former California attorney general overly self-seeking. That buzz has only grown as Harris, a former prosecutor, gets ready to take on Vice President Mike Pence, in Wednesday night’s vice presidential debate.

It turns out, however, that American voters don’t penalize women who seem ambitious, according to a new paper published in the journal Political Behavior by Sparsha Saha, M.A. ’10 Ph.D. ’14, a political scientist and lecturer in Harvard’s Government Department. Despite the vast body of literature on voter behavior, Saha and her co-author, Ana Catalano Weeks, Ph.D. ’16, assistant professor at the University of Bath, say it’s the first study of voter perceptions of candidate ambition.

The pair’s work builds on several studies done by Harvard researchers and others over the years that consistently show that when women ask for raises or promotions, they are often penalized in the workplace.

“After [Clinton’s] loss, a lot of the framing and the focus had been on ‘Was she too ambitious for people?’” said Saha.

“And it seemed like what Clinton was doing was asking for the biggest promotion,” said Weeks. “And so we thought … does that translate into politics?”

American voters don’t penalize women who seem ambitious, says co-author Sparsha Saha, a political scientist and lecturer in Harvard’s Government Department.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

A woman who’s seen as tough or determined, pushing for broad policy changes, or juggling family and public life are not shortcomings for Democrats or Republican voters, the study found. But there is a difference when it comes to running for higher office. Democrats are more supportive of women candidates than Republicans by a 7-point margin, a “significant difference,” the authors say. And Republicans are generally more inclined to support men seeking higher office than women by a 5-point spread — they particularly favor men, but not women, with traits suggesting ambition, like “tough negotiator” and “determined to succeed,” according to the paper.

The researchers identified four types of voter-perceived ambition: “progressive” for the internal drive to seek higher office; “personalistic” for traits associated with ambition; “agenda-based” for perceptions about candidates who call for broad or systemic changes; and “parental,” those judged on how well or poorly they juggle family and work.

In experiments, respondents were asked to choose between two candidates in hypothetical elections with randomly assigned attributes, some of which implied different kinds of ambition, and then later explain why they preferred one candidate over another.

“Once we disaggregated these different types of ambition, we were able to say Republicans and Democrats are both OK with personalistic and agenda-based ambition, so women on the right and the left should lean into those kinds of ambition,” said Saha.

These findings, the study suggests, may offer insight into why some women candidates, like former Alaska governor and GOP vice presidential nominee Sarah Palin and New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, didn’t suffer from being perceived as ambitious. Voters saw Palin as a “maverick” intent on upending the mainstream agenda, and Ocasio-Cortez as a bold and determined personality who pushed policies and programs to lift up working-class Americans.

Ana Catalano Weeks, assistant professor at the University of Bath, is co-author of the paper.

Courtesy photo

In open-ended questions, Democrats “overwhelmingly” mentioned gender as a reason they chose one candidate over another, citing the need for more women in power. When Republicans brought up gender in their answers, it was only in the context of male candidates, whom they favored by a 2:1 ratio, the researchers found.

“I think what convinced me that what we’re finding is actually very credible is that it chimes really well with real-world data, observational data, which suggests that when women run for office, they win,” said Weeks.

A record number of women currently serve in the 116th Congress: 105 in the House and 26 in the Senate. In the upcoming 2020 election, women make up 36 percent of all candidates in House races and 31 percent of nominees in the 33 Senate races that have selected nominees.

The authors hope the findings begin to clear up longstanding misconceptions that may be holding some women back from jumping into politics.

“I think it really is very reassuring, and I hope that women themselves who are thinking about politics look at this and are hopeful, and candidates who are running are also hopeful, but maybe more importantly in some ways, or as important, is party gatekeepers, who tend to be older men, look at this and note that voters are not really concerned about this,” said Saha.