Illustration by Ben Boothman

Trailblazing initiative marries ethics, tech

Computer science, philosophy faculty ask students to consider how systems affect society

First in a four-part series that taps the expertise of the Harvard community to examine the promise and potential pitfalls of the rising age of artificial intelligence and machine learning, and how to humanize it.

For two decades, the flowering of the Digital Era has been greeted with blue-skies optimism, defined by an unflagging belief that each new technological advance, whether more powerful personal computers, faster internet, smarter cellphones, or more personalized social media, would only enhance our lives.

But public sentiment has curdled in recent years with revelations about Silicon Valley firms and online retailers collecting and sharing people’s data, social media gamed by bad actors spreading false information or sowing discord, and corporate algorithms using opaque metrics that favor some groups over others. These concerns multiply as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine-learning technologies, which made possible many of these advances, quietly begin to nudge aside humans, assuming greater roles in running our economy, transportation, defense, medical care, and personal lives.

“Individuality … is increasingly under siege in an era of big data and machine learning,” says Mathias Risse, Littauer Professor of Philosophy and Public Administration and director of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard Kennedy School. The center invites scholars and leaders in the private and nonprofit sectors on ethics and AI to engage with students as part of its growing focus on the ways technology is reshaping the future of human rights.

Building more thoughtful systems

Even before the technology field belatedly began to respond to market and government pressures with promises to do better, it had become clear to Barbara Grosz, Higgins Research Professor of Natural Sciences at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), that the surest way to get the industry to act more responsibly is to prepare the next generation of tech leaders and workers to think more ethically about the work they’ll be doing. The result is Embedded EthiCS, a groundbreaking novel program that marries the disciplines of computer science and philosophy in an attempt to create change from within.

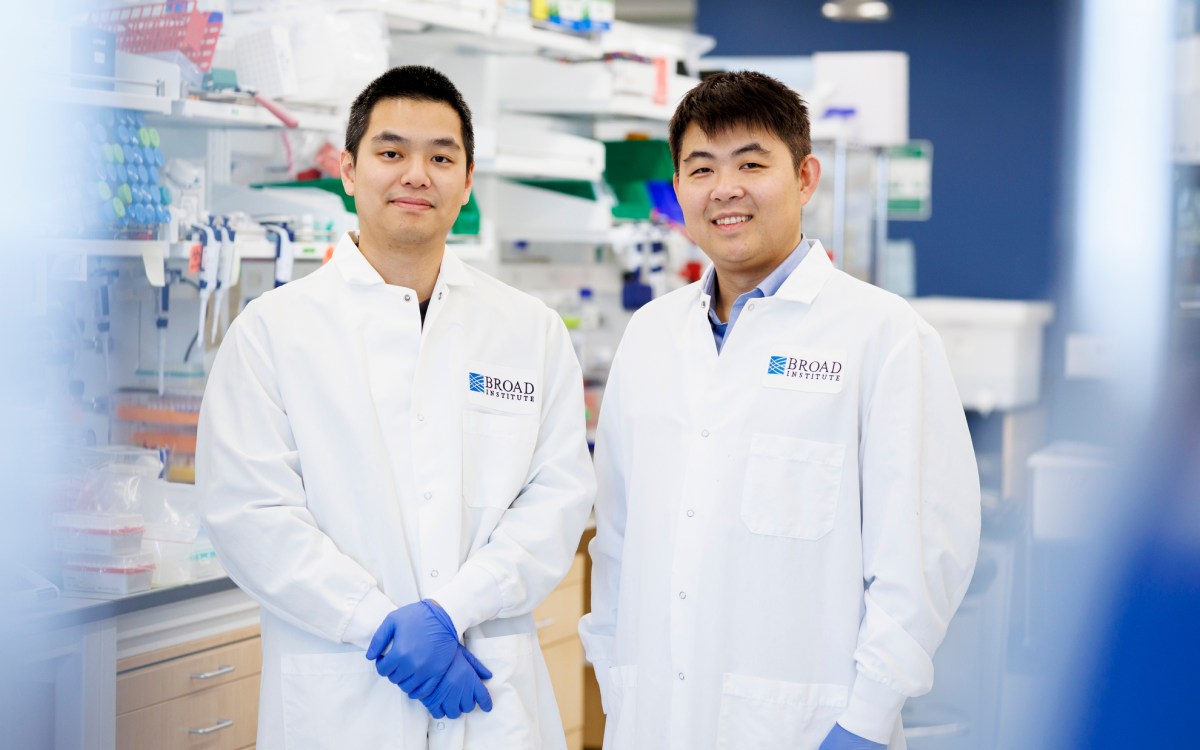

The timing seems on target, since the revolutionary technologies of AI and machine learning have begun making inroads in an ever-broadening range of domains and professions. In medicine, for instance, systems are expected soon to work effectively with physicians to provide better healthcare. In business, tech giants like Google, Facebook, and Amazon have been using smart technologies for years, but use of AI is rapidly spreading, with global corporate spending on software and platforms expected to reach $110 billion by 2024.

“A one-off course on ethics for computer scientists would not work. We needed a new pedagogical model.”

— Alison Simmons, the Samuel H. Wolcott Professor of Philosophy

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

So where are we now on these issues, and what does that mean? To answer those questions, this Gazette series will examine emerging technologies in medicine and business, with the help of various experts in the Harvard community. We’ll also take a look at how the humanities can help inform the future coordination of human values and AI efficiencies through University efforts such as the AI+Art project at metaLAB(at)Harvard and Embedded EthiCS.

In spring 2017, Grosz recruited Alison Simmons, the Samuel H. Wolcott Professor of Philosophy, and together they founded Embedded EthiCS. The idea is to weave philosophical concepts and ways of thinking into existing computer science courses so that students learn to ask not simply “Can I build it?” but rather “Should I build it, and if so, how?”

Through Embedded EthiCS, students learn to identify and think through ethical issues, explain their reasoning for taking, or not taking, a specific action, and ideally design more thoughtful systems that reflect basic human values. The program is the first of its kind nationally and is seen as a model for a number of other colleges and universities that plan to adapt it, including Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Stanford University.

In recent years, computer science has become the second most popular concentration at Harvard College, after economics. About 2,750 students have enrolled in Embedded EthiCS courses since it began. More than 30 courses, including all classes in the computer science department, participated in the program in spring 2019.

Students learn to ask not simply “Can I build it?” but rather “Should I build it, and if so, how?”

“We don’t need all courses, what we need is for enough students to learn to use ethical thinking during design to make a difference in the world and to start changing the way computing technology company leaders, systems designers, and programmers think about what they’re doing,” said Grosz.

It became clear that Harvard’s computer science students wanted and needed something more just a few years ago, when Grosz taught “Intelligent Systems: Design and Ethical Challenges,” one of only two CS courses that had integrated ethics into the syllabus at the time.

During a class discussion about Facebook’s infamous 2014 experiment covertly engineering news feeds to gauge how users’ emotions were affected, students were outraged by what they viewed as the company’s improper psychological manipulation. But just two days later, in a class activity in which students were designing a recommender system for a fictional clothing manufacturer, Grosz asked what information they thought they’d need to collect from hypothetical customers.

“It was astonishing,” she said. “How many of the groups talked about the ethical implications of the information they were collecting? None.”

When she taught the course again, only one student said she thought about the ethical implications, but felt that “it didn’t seem relevant,” Grosz recalled.

“You need to think about what information you’re collecting when you’re designing what you’re going to collect, not collect everything and then say ‘Oh, I shouldn’t have this information,’” she explained.

Making it stick

Seeing how quickly even students concerned about ethics forgot to consider them when absorbed in a technical project prompted Grosz to focus on how to help students keep ethics up front. Some empirical work shows that standalone courses aren’t very sticky with engineers, and she was also concerned that a single ethics course would not satisfy growing student interest. Grosz and Simmons designed the program to intertwine the ethical with the technical, thus helping students better understand the relevance of ethics to their everyday work.

In a broad range of Harvard CS courses now, philosophy Ph.D. students and postdocs lead modules on ethical matters tailored to the technical concepts being taught in the class.

“We want the ethical issues to arise organically out of the technical problems that they’re working on in class,’” said Simmons. “We want our students to recognize that technical and ethical challenges need to be addressed hand in hand. So a one-off course on ethics for computer scientists would not work. We needed a new pedagogical model.”

Key issues

Examples of ethical problems courses are tackling

Image gallery

Are software developers morally obligated to design for inclusion?

Should social media companies suppress the spread of fake news on their platforms?

Should search engines be transparent about how they rank results?

Should we think about electronic privacy as a right?

Getting comfortable with a humanities-driven approach to learning, using the ideas and tools of moral and political philosophy, has been an adjustment for the computer-science instructors as well as students, said David Grant, who taught as an Embedded EthiCS postdoc in 2019 and is now assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

“The skill of ethical reasoning is best learned and practiced through open and inclusive discussion with others,” Grant wrote in an email. “But extensive in-class discussion is rare in computer science courses, which makes encouraging active participation in our modules unusually challenging.”

Students are used to being presented problems for which there are solutions, program organizers say. But in philosophy, issues or dilemmas become clearer over time, as different perspectives are brought to bear. And while sometimes there can be right or wrong answers, solutions are typically thornier and require some difficult choices.

“This is extremely hard for people who are used to finding solutions that can be proved to be right,” said Grosz. “It’s fundamentally a different way of thinking about the world.”

“They have to learn to think with normative concepts like moral responsibility and legal responsibility and rights. They need to develop skills for engaging in counterfactual reasoning with those concepts while doing algorithm and systems design” said Simmons. “We in the humanities problem-solve too, but we often do it in a normative domain.”

“What we need is for enough students to learn to use ethical thinking during design to make a difference in the world.”

— Barbara Grosz, Higgins Research Professor of Natural Sciences at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The importance of teaching students to consider societal implications of computing systems was not evident in the field’s early days, when there were only a very small number of computer scientists, systems were used largely in closed scientific or industry settings, and there were few “adversarial attacks” by people aiming to exploit system weaknesses, said Grosz, a pioneer in the field. Fears about misuse were minimal because so few had access.

But as the technologies have become ubiquitous in the past 10 to 15 years, with more and more people worldwide connecting via smartphones, the internet, and social networking, as well as the rapid application of machine learning and big data computing since 2012, the need for ethical training is urgent. “It’s the penetration of computing technologies throughout life and its use by almost everyone now that has enabled so much that’s caused harm lately,” said Grosz.

That apathy has contributed to the perceived disconnect between science and the public. “We now have a gap between those of us who make technology and those of us who use it,” she said.

Simmons and Grosz said that while computer science concentrators leaving Harvard and other universities for jobs in the tech sector may have the desire to change the industry, until now they haven’t been furnished with the tools to do so effectively. The program hopes to arm them with an understanding of how to identify and work through potential ethical concerns that may arise from new technology and its applications.

“What’s important is giving them the knowledge that they have the skills to make an effective, rational argument with people about what’s going on,” said Grosz, “to give them the confidence … to [say], ‘This isn’t right — and here’s why.’”

“It is exciting. It’s an opportunity to make use of our skills in a way that might have a visible effect in the near- or midterm.”

— Jeffrey Behrends, co-director of Embedded EthiCS

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

A winner of the Responsible CS Challenge in 2019, the program received a $150,000 grant for its work in technology education that helps fund two computer science postdoc positions to collaborate with the philosophy student-teachers in developing the different course modules.

Though still young, the program has also had some nice side effects, with faculty and graduate students in the two typically distant cohorts learning in unusual ways from each other. And for the philosophy students there’s been an unexpected boon: working on ethical questions at technology’s cutting edge. It has changed the course of their research and opened up new career options in the growing field of engaged ethics.

“It is exciting. It’s an opportunity to make use of our skills in a way that might have a visible effect in the near- or midterm,” said philosophy lecturer Jeffrey Behrends, one of the program’s co-directors.

Will this ethical training reshape the way students approach technology once they leave Harvard and join the workforce? That’s the critical question to which the program’s directors are now turning their attention. There isn’t enough data to know yet, and the key components for such an analysis, like tracking down students after they’ve graduated to measure the program’s impact on their work, present a “very difficult evaluation problem” for researchers, said Behrends, who is investigating how best to measure long-term effectiveness.

Ultimately, whether stocking the field with designers, technicians, executives, investors, and policymakers will bring about a more responsible and ethical era of technology remains to be seen. But leaving the industry to self-police or wait for market forces to guide reforms clearly hasn’t worked so far.

“Somebody has to figure out a different incentive mechanism. That’s where really the danger still lies,” said Grosz of the industry’s intense profit focus. “We can try to educate students to do differently, but in the end, if there isn’t a different incentive mechanism, it’s quite hard to change Silicon Valley practice.”

Next: Ethical concerns rise as AI takes an ever larger decision-making role in many industries.