iStock

Enzymatic DNA synthesis sees the light

Methods from the computer chip industry aid writing and storage of digital data in DNA

According to current estimates, the amount of data produced by humans and machines is rising at an exponential rate, with the digital universe doubling in size every two years. Very likely, the magnetic and optical data-storage systems at our disposal won’t be able to archive this fast-growing volume of digital 1s and 0s anymore at some point. Plus, they cannot safely store data for more than a century without degrading.

One solution to this pending global data-storage problem could be the development of DNA — life’s very own information-storage system — into a digital data storage medium.

Researchers already are encoding complex information consisting of digital code into DNA’s four-letter code comprised of its A, T, G, and C nucleotide bases. DNA is an ideal storage medium because it is stable over hundreds or thousands of years, has an extraordinary information density, and its information can be efficiently read (decoded) again with advanced sequencing techniques that are continuously getting less expensive.

What lags behind is the ability to write (encode) information into DNA. The programmed synthesis of synthetic DNA sequences still is mostly performed with a decades-old chemical procedure, known as the “phosphoramidite method,” that takes many steps that, although being able to be multiplexed, can only generate DNA sequences with up to around 200 nucleotides in length and makes occasional errors. It also produces environmentally toxic by-products that are not compatible with a “clean data storage technology.”

Previously, George Church’s team at Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and Harvard Medical School (HMS) has developed the first DNA storage approach that uses a DNA-synthesizing biological enzyme known as Terminal deoxynucleotidyl Transferase (TdT), which, in principle, can synthesize much longer DNA sequences with fewer errors. Now, the researchers have applied photolithographic techniques from the computer chip industry to enzymatic DNA synthesis, and thus developed a new method to multiplex TdT’s superior DNA writing ability. In their study published in Nature Communications, they demonstrated the parallel synthesis of 12 DNA strands with varying sequences on a 1.2 square millimeter array surface.

“We have championed and intensively pursued the use of DNA as a data-archiving medium accessed infrequently, yet with very high capacity and stability. Breakthroughs by us and others have enabled an exponential rise in the amount of digital data encrypted in DNA,” said corresponding author Church. “This study and other advances in enzymatic DNA synthesis will push the envelope of DNA writing much further and faster than chemical approaches.”

Church is a core faculty member at the Wyss Institute and lead of its Synthetic Biology Focus Area with DNA data storage as one of its technology development areas. He also is professor of genetics at HMS and Professor of Health Sciences and Technology at Harvard and MIT.

While the group’s first strategy using the TdT enzyme as an effective tool for DNA synthesis and digital data storage controlled TdT’s enzyme activity with a second enzyme, they show in their new study that TdT can be controlled by the high-energy photons that UV-light is composed of. A high level of control is essential as the TdT enzyme needs to be instructed to add only one single or a short block made of one of the four A, T, G, C nucleotide bases to the growing DNA strand with high precision at each cycle of the DNA synthesis process.

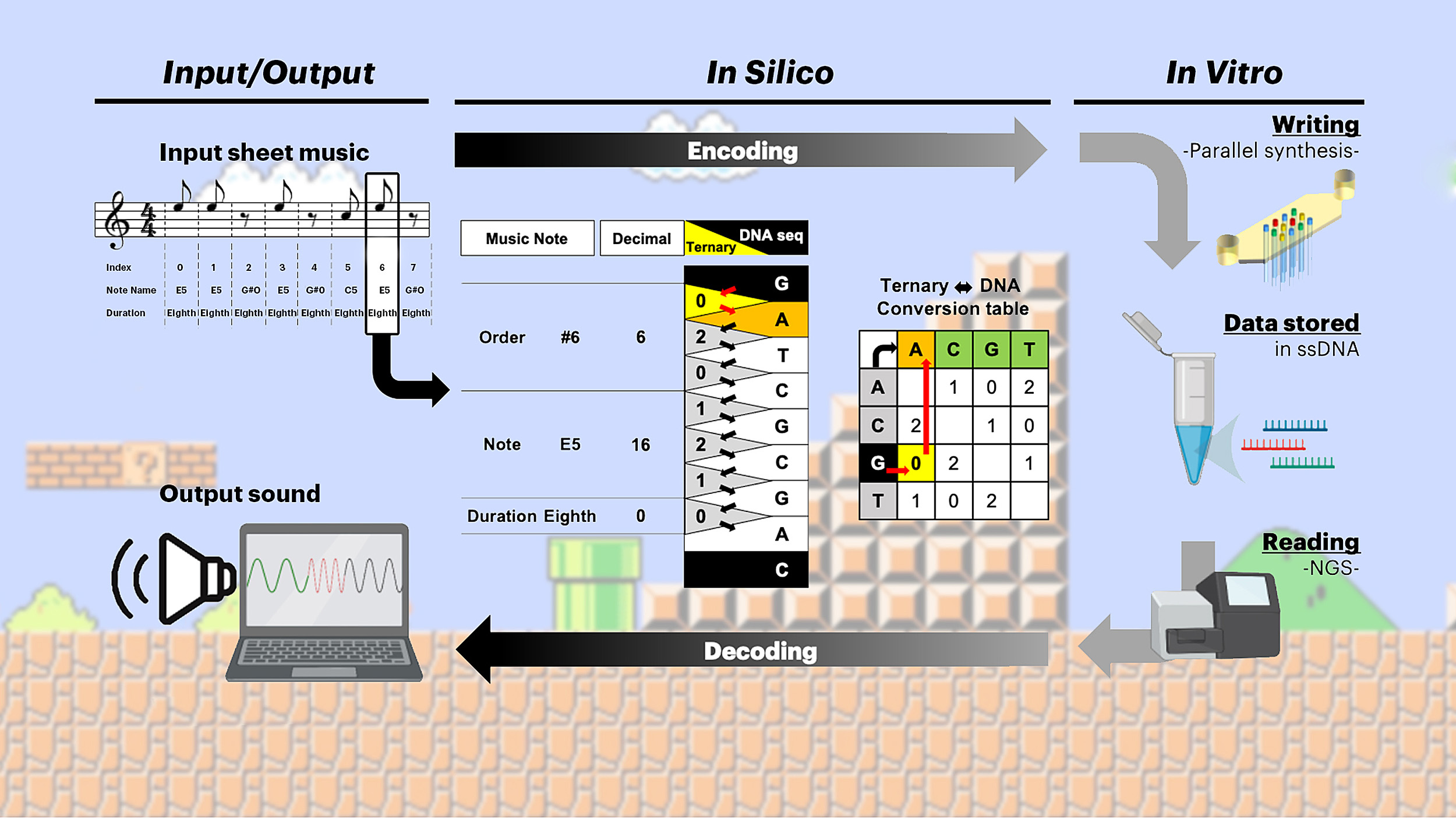

This illustration shows how the Wyss’ team encoded the first measures of the 1985 Nintendo Entertainment System video game Super Mario BrothersTM “Overworld Theme” (input) in DNA and then decoded it again into a sound-bite (output).

Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

Using a special codec, a computational method that encodes digital information into DNA code and decodes it again, which Church’s team developed in their previous study, the researchers encoded the first two measures of the “Overworld Theme” sheet music from the 1985 Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) video game Super Mario Brothers within 12 synthetic DNA strands. They generated those strands on an array matrix with a surface measuring merely 1.2 square millimeters by extending short DNA “primer” sequences, which were extended in a 3×4 pattern, using their photolithographic approach.

“We applied the same photolithographic approach used by the computer chip industry to manufacture chips with electrical circuits patterned with nanometer precision to write DNA,” said first author Howon Lee, a postdoctoral fellow in Church’s group at the time of the study. “This provides enzymatic DNA synthesis with the potential of unprecedented multiplexing in the production of data-encoding DNA strands.”

Photolithography, like photography, uses light to transfer images onto a substrate to induce a chemical change. The computer chip industry miniaturized this process and uses silicon instead of film as a substrate. Church’s team now adapted the chip industry’s capabilities in their new DNA writing approach by substituting silicon with their array matrix consisting of microfluidic cells containing the short DNA primer sequences.

In order to control DNA synthesis at primers positioned in the 3×4 pattern, the team directed a beam of UV-light onto a dynamic mask (as is done in computer chip manufacturing) — which essentially is a stencil of the 3×4 pattern in which DNA synthesis is activated — and shrunk the patterned beam on the other side of the mask with optical lenses down to the size of the array matrix.

“The UV-light reflected from the mask pattern precisely hits the target area of primer elongation and frees up cobalt ions, which the TdT enzyme needs in order to function, by degrading a light-sensitive “caging” molecule that shields the ions from TdT,” said co-author Daniel Wiegand, research scientist at the Wyss Institute. “By the time the UV-light is turned off and the TdT enzyme deactivated again with excess caging molecules, it has added a single nucleotide base or a homopolymer block of one of the four nucleotide bases to the growing primer sequences.”

This cycle can be repeated multiple times whereby in each round only one of the four nucleotide bases or a homopolymer of a specific nucleotide base is added to the array matrix. In addition, by selectively covering specific openings of the mask during each cycle, the TdT enzyme only adds that specific nucleotide base to DNA primers where it is activated by UV-light, allowing the researchers to fully program the sequence of nucleotides in each of the strands.

“Photon-directed multiplexed enzymatic DNA synthesis on this newly instrumented platform can be further developed to enable much higher automated multiplexing with improved TdT enzymes, and, eventually make DNA-based data storage significantly more effective, faster, and cheaper,” said co-corresponding author Richie Kohman, a lead senior research scientist at the Wyss’ Synthetic Biology focus area, who helped coordinate the research in Church’s team at the Wyss Institute.

“This new approach to enzyme-directed synthetic DNA synthesis by the Church team is a clever piece of bioinspired engineering that combines the power of DNA replication with one of the most controllable and robust manufacturing methods developed by humanity — photolithography — to provide a solution that brings us closer to the goal of establishing DNA as a usable data storage medium,” said the Wyss Institute’s Founding Director Don Ingber, who is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, and Professor of Bioengineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS).

Other authors on the study are additional members of Church’s team, including Kettner Griswold, and Sukunya Punthambaker, as well as Honggu Chun, Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Korea University. This work was funded by the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering.