Exploring Coke’s role in obesity strategy in China, elsewhere

Harvard researcher looks at how company helped shape health science, policy

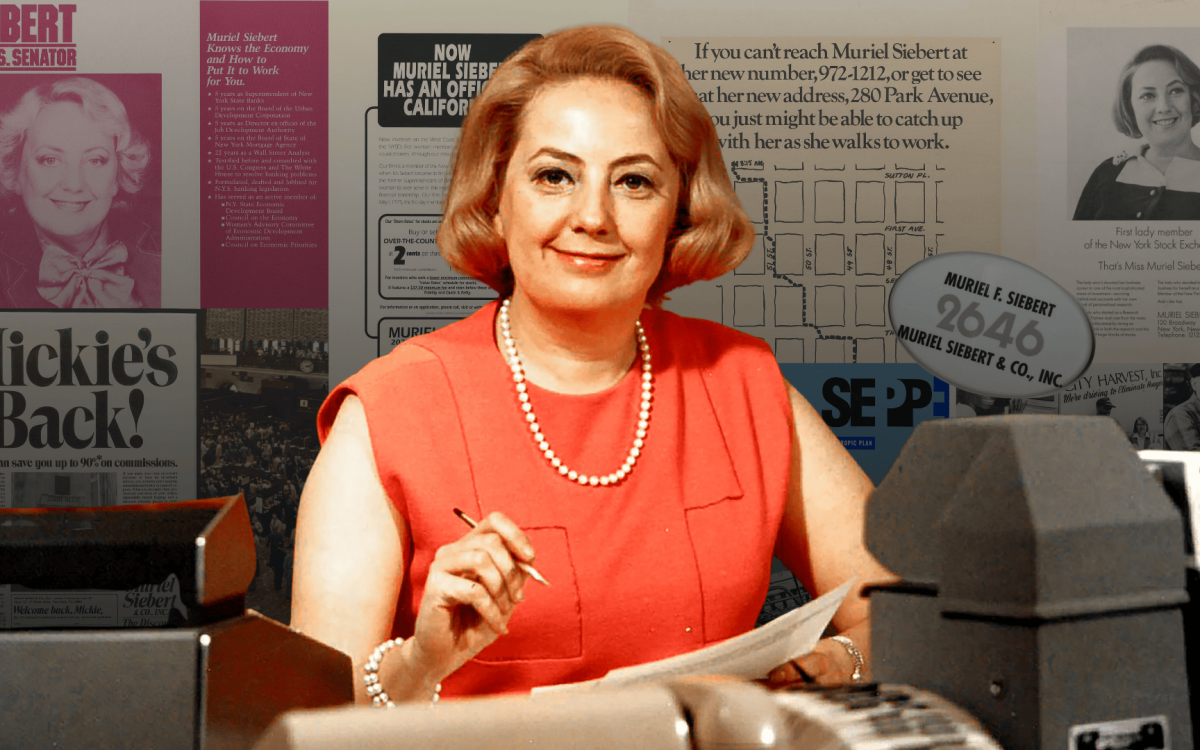

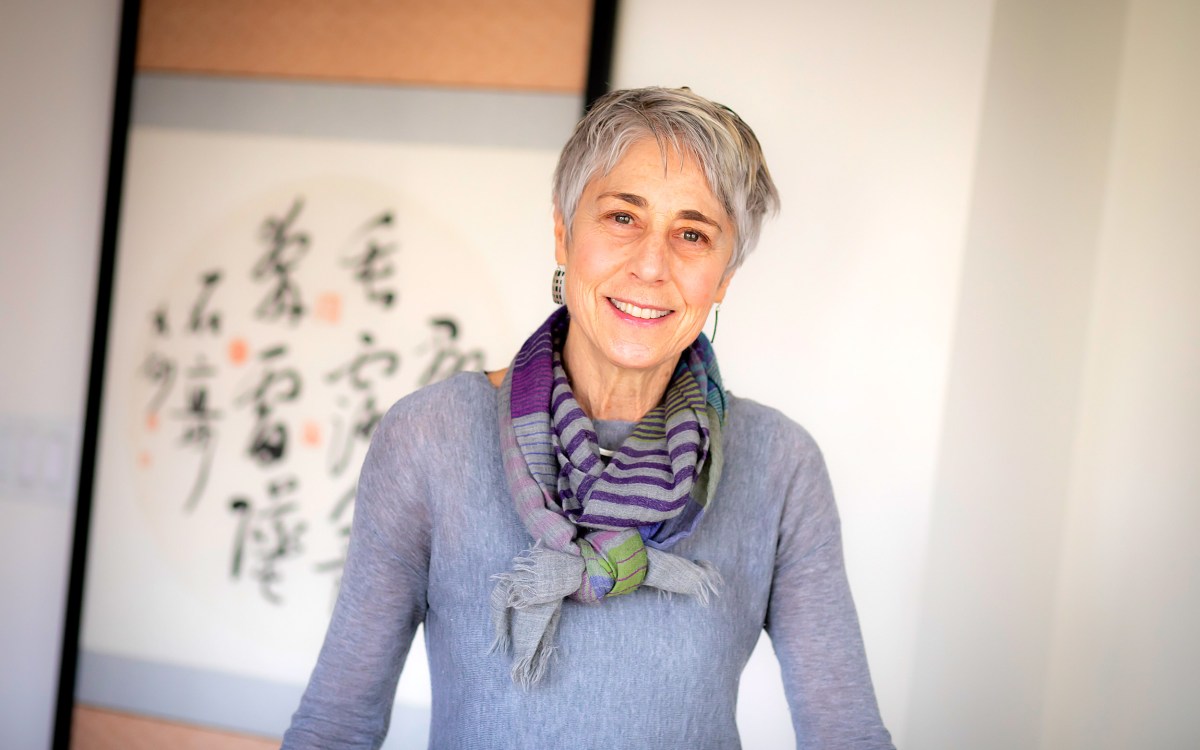

Harvard Professor Susan Greenhalgh says Coca-Cola used a nonprofit to shape obesity science and policy solutions in China.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

Last year, anthropologist Susan Greenhalgh, the John King and Wilma Cannon Fairbank Research Professor of Chinese Society, revealed how the Coca-Cola Co. worked through an industry-funded global scientific nonprofit based in Washington, D.C., to influence obesity science and policy solutions in China. In a follow-up study, published Monday in the Journal of Health Policy, Politics and Law, Greenhalgh went deeper into how the nonprofit, the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI), was so successful at this. She traces the history of ILSI (the chief scientific nonprofit of the processed food and sugary drinks industry), exploring how it operates, and how Coca-Cola used it to influence the scientific agenda and shape obesity science and policy at global levels and in China. The Gazette interviewed Greenhalgh about the new study and what it says about industry influence on health science and policy.

Q&A

Susan Greenhalgh

GAZETTE: What’s the story you’re trying to tell here, and how does it expand on the 2019 report?

GREENHALGH: This is fundamentally a story about Coke and ILSI protecting the soda industry from threats posed by the obesity epidemic — threats of soda taxes and government restrictions on marketing to kids. Since 2015, when The New York Times exposed Coke’s efforts to promote activity as the main solution for obesity, we’ve known that Coke was involved in distorting the science of obesity. My work reveals the scale of the impact and the inner workings of the organizations involved. The 2019 papers I published in The BMJ and the Journal of Public Health Policy documented Coke and ILSI’s success in getting the “exercise-first” approach embedded in China’s science and policy on obesity. This article digs into the operations of ILSI to explain that success during the two decades between 1995, when ILSI took up the obesity issue, and 2015, when Coke abandoned the exercise-first approach.

“ … we’ve known that Coke was involved in distorting the science of obesity. My work reveals the scale of the impact and the inner workings of the organizations involved.”

GAZETTE: You break the report into two parts. The first is an institutional story of how ILSI works both at global and local levels to advance corporate interests. It takes a behind-the-scenes look at the organization. Then, the report highlights the gap between the public narrative about ILSI as a charitable organization that adheres to IRS rules on nonprofits, and contrasts it with set of private channels within the organization used to influence ILSI science and health policy in branches around the world. What were some of the biggest revelations you came across here?

GREENHALGH: ILSI was created more than 40 years ago by then-Coca-Cola vice president Alex Malaspina and it now has 15 branches worldwide, including one in China — but nobody had looked closely at how it operates. The biggest discovery was the incredible complexity and sophistication of the organization. Tracking it over six years, I discovered that there were four specific features of its structure and organization that enabled it to serve industry interests while appearing to serve the public. You just mentioned two of those features: ILSI has a dual character — visible and invisible, public and private — and a host of informal, hidden mechanisms by which companies can influence the science. But there are two more as well. One is a hierarchical global structure that concentrated power in D.C. and made the branches subject to the authority of ILSI-Global. Last but not least are exclusionary rules of participation. Participation in ILSI events — especially by speakers — was by invitation only, creating a quasi-closed world of ILSI science in which critics of corporate intervention in science were not invited. They were excluded by definition.

GAZETTE: What do you hit on in the second part of the report?

GREENHALGH: The second part is a detailed story of science-making and policymaking over 20 years, both at the global level of ILSI headquarters in the U.S. and at the local Chinese level. This story shows how Coke and other corporations used the ILSI apparatus to promote an industry-friendly approach to obesity calling for some dietary changes, but prioritizing exercise and remaining silent about soda taxes. In this section, I trace the process step by step to show how Coca-Cola managed to leave its mark on every phase of the process of making obesity policy. You can find Coke’s fingerprints on everything from framing the obesity problem and solution as matters primarily of physical activity, to naming the key, industry-friendly actors in the policy process, to creating activity-focused policies and programs. You can see Coke’s involvement too in the construction of the scientific rationales to support the physical-activity solution, primarily “energy-balance science,” which says you can eat as many calories as you wish, as long as you burn them off. Finally, you can detect Coke’s role in incorporating these activity-centered approaches into Chinese policy and programs. That’s pretty remarkable.

GAZETTE: What triggered this study, along with the previous two, and how did you go about completing this body of work?

GREENHALGH: When I started this project back in 2013, there was already growing concern about corporate intervention in science and policy on human health. There were important studies of the tobacco and pharmaceutical industries, some by colleagues here at Harvard, but there was virtually no research on the food industry. At that time, the media were devoting massive attention to the growing epidemic of obesity, not just in the U.S but all around the world. It seemed highly likely the food industry was trying to skew the science of obesity to protect profits, and so I set out to study what the industry was doing in China, my area of expertise.

There, I spent 10 weeks doing in-depth field research that involved, among other things, two dozen interviews with obesity experts, including those who had been instrumental in making China’s obesity policy. The interviews raised more questions than they answered, though. The biggest puzzle was ILSI, whose leaders in China claimed to create disinterested science despite being industry-funded. To understand developments in China, I needed to expand the project to include the entire ILSI-Global network, the Coca-Cola Co., and other global programs active in China, like the Exercise Is Medicine program. Over time, my research became a two-part project, with one part centering on China and the other on developments at the global level, which became interesting in their own right.

“No one I was studying wanted me to be studying them. And so they put many obstacles in my way.”

GAZETTE: Did you encounter any challenges collecting the data and information?

GREENHALGH: Absolutely. Everything was surrounded in secrecy. Many of the claims made by people involved with ILSI-funded science didn’t add up; the closer you looked, the more problematic some of them became. Over time, I came to see that the main actors — both ILSI leaders at global and local levels and the core scientists — were engaged in deliberately concealing what was going on. So, much of the research involved constantly trying to peel back layer after layer of obfuscation.

The second major challenge was there was no roadmap to what I should study — which actors, which organizations, which activities. As a result, I had to adopt an open-ended, exploratory process of investigation and follow every lead to see where it would take me. It was an energizing process, because the more I looked, the more interesting — and often concerning — material I found.

GAZETTE: What are some of the study’s limitations?

GREENHALGH: No one I was studying wanted me to be studying them. And so they put many obstacles in my way. Because of the extreme sensitivity of the issues I was probing — especially after The Times’ expose — I was unable to interview the core scientists in the U.S.

Fortunately, this problem didn’t affect the China research. Partly because it was done before the 2015 expose came out, but also because the political culture in China is very different. In China, corporate funding of scientific research is just routine. It’s business as usual, so people were willing to talk about it.

GAZETTE: Why is it important that these issues be brought to the light?

GREENHALGH: It’s important for two major reasons. First, despite some important critical work on corporate intervention in science, rich and powerful companies like Coca-Cola are continuing their efforts to create industry-friendly science, and that science threatens both the integrity of health science and the soundness of health policy. We’ve long known that food companies are meddling in the science, but we still know little about how they’re doing it and with what effects. If we are to intervene in these harmful dynamics, we need to know much more about how sophisticated, secretive quasi-corporate organizations like ILSI work.

The second reason we need to keep these issues in the public eye — even in the midst of a viral pandemic — is that the impact of these companies may be much greater than is currently appreciated. Industry impact is likely to be greatest not in the U.S. or Western Europe, where the critical research is concentrated, but in countries in the Global South that are part of the ILSI network. If China is any indication, the political culture, especially in poor countries, may be welcoming to big companies offering financial and technological support. Substantial evidence suggests that ILSI operates in similar ways across the globe. We need to put much more energy into in-depth research on the effects ILSI is having on scientific understandings and official policies on chronic diseases around the world.

In China the impact of that exercise-first approach promoted by Coke and ILSI continues to this day. Despite the findings of the 2019 articles, China has not questioned how it’s tackling its epidemics of obesity and related chronic diseases. I see this new work as both a call to action to the research community, and a concrete guide to the kinds of analytic strategies and research methods that are needed to call the food industry to account.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.