Harvard Professor Deidre Lynch and faculty from dozens of universities around the world tackled “Clarissa” during lockdown.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Befriending ‘Clarissa’ during lockdown

Very long, even for academic book club, but themes of morality, isolation resonated

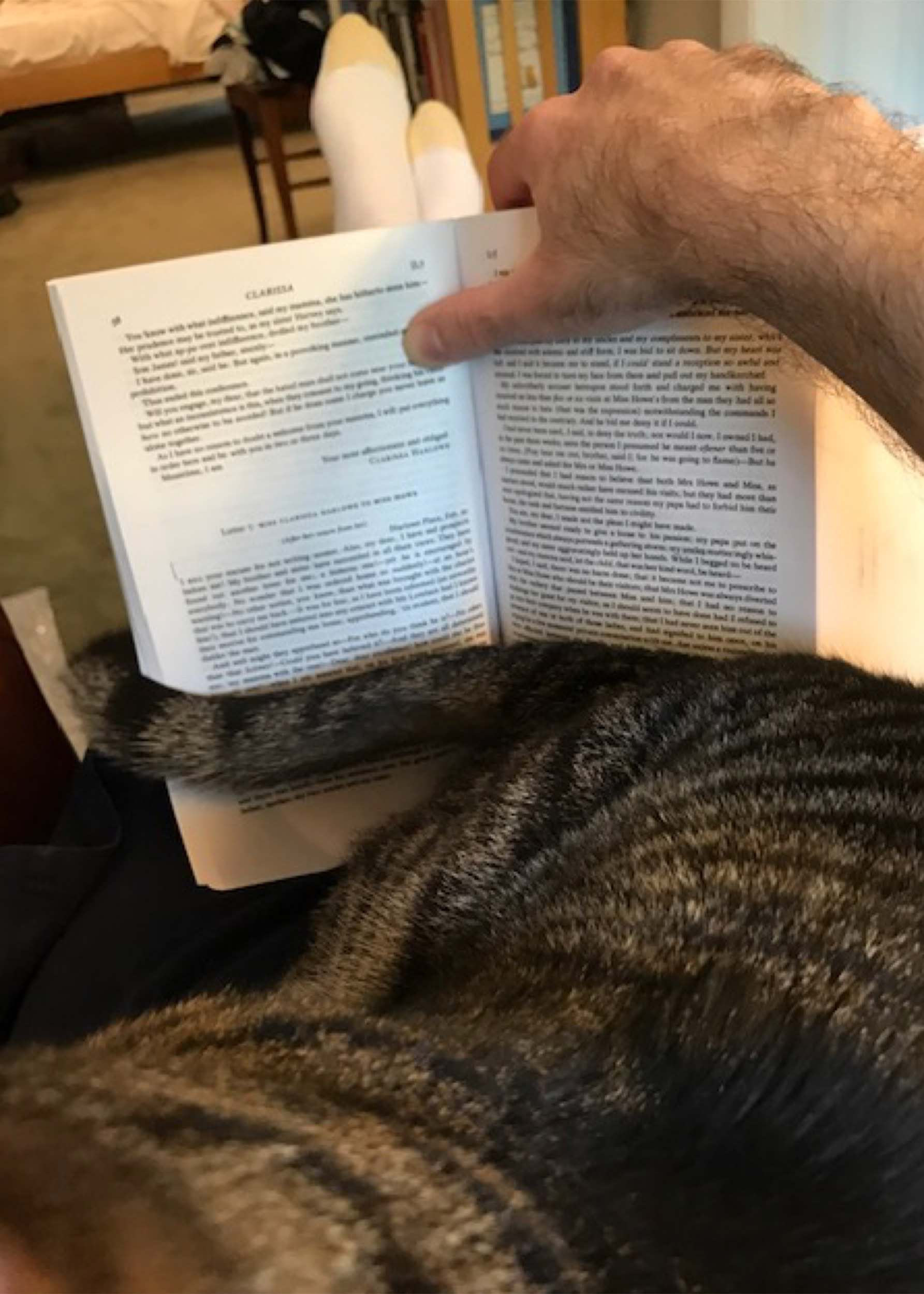

When the pandemic upended life in Cambridge, Deidre Lynch fled to her hometown of Toronto, where the Ernest Bernbaum Professor of Literature found herself facing the end of what was a sabbatical year with only her husband, beloved cat Mr. Bean, and three works of fiction.

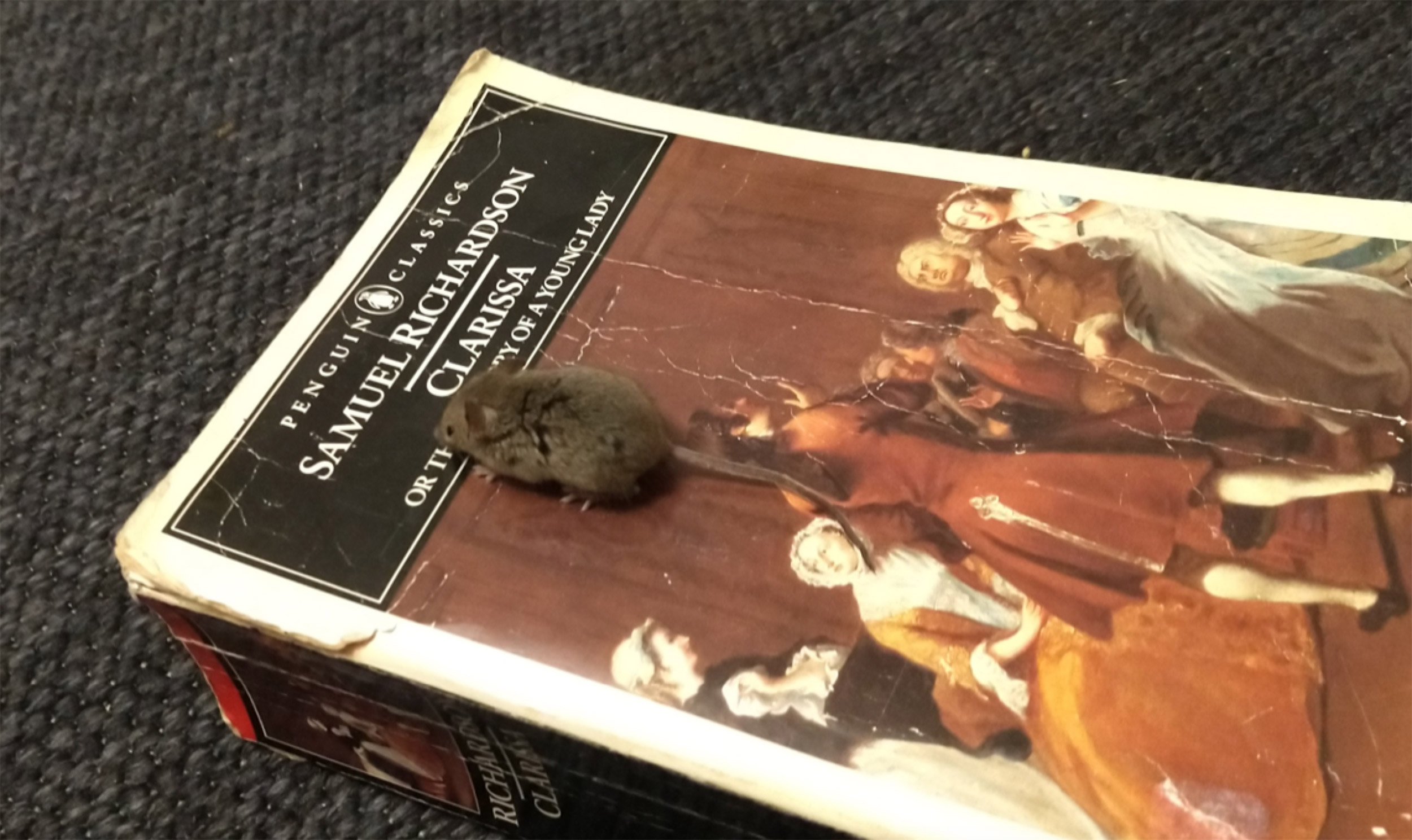

One was a heavily dog-eared Penguin paperback copy of “Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady,” an 18th-century novel by Samuel Richardson that follows Clarissa’s pursuit and rape by an aggressive suitor named Lovelace. The novel is notorious for its difficult themes of morality, gender, and class, but also its length: nearly 1,500 pages. Lynch had taught undergraduates the book in its abridged form for more than a decade, but the copy in her home was the unabridged version narrated through 537 letters, most of them written by the protagonist and her aggressor.

With time flattened by quarantine, Lynch proposed a reading group with her friend Yoon Sun Lee ’87, an English professor at Wellesley College. “Clarissa,” in Lockdown, Together was born.

“There was so much aspirational reading going on in May,” recalled Lynch. “I thought, ‘I’m going to use lockdown to reread ‘War and Peace,’ but ‘Clarissa’ is just as important to the genre. Then Leah [Whittington of Harvard’s English Department] announced the group on the new Early Modern World listserv at Harvard. We started the first week of June.”

Faculty word-of-mouth spread quickly among dozens of colleges and universities across the globe, and soon a group of 50 had signed on for the biweekly get-togethers. Members committed to read 100 pages a week, which brought the reading to completion Sept. 11.

“It’s not just a book; it’s a way of life, and it changes people.”

Deirdre Lynch

“The novel moves from January to November, so we felt as if our calendar would merge with Clarissa’s, but we also wanted to finish before the semester got underway,” said Lynch. “It’s not just a book; it’s a way of life, and it changes people.”

Ramie Targoff, who teaches Renaissance literature at Brandeis, joined to read “Clarissa” for the first time, though she had read Richardson’s more famous “Pamela” in her high school AP English class. She likened the project to training to run a marathon, which she had previously attempted but never completed.

“I bought the physical book so I could feel the progress,” she said. “I was the strict 15-page-a-day reader. I did it like I do my yoga practice. I would choose the time of day when I wanted a hit of ‘Clarissa.’” But she found she had to read in small doses, because she could sometimes barely stand the “emotionally wrenching” passages.

“I couldn’t read big swaths,” she said. “Just when you thought nothing could get worse, it did. And it often overlapped with the horrendous news in our country. The dates of the novel corresponded almost exactly with the COVID crisis.”

The discussions were lively, and to keep the conversation going outside the formal meeting, Alex Creighton, a Harvard Ph.D. student in English in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS), organized a blog with the reading group’s name. There they posted on a variety of topics including: how relatable were Clarissa’s isolating and prison-like experiences in this time of pandemic; how sating the epistolary form felt; and how seeing Mary Trump interviewed on MSNBC connected directly to the book.

Wrote Martin Quinn, a Ph.D. candidate in English in GSAS: “profoundly more compelling visually was the only legible title in [the] shot, perched perfectly over Mary’s right shoulder: a vast, looming, two-volume ‘Clarissa.’ Was she trying to tell us something? Or has the culture finally memed and Zoomed its way into critical and archival self-awareness? Or are those of us neck-deep in Richardson simply apt to see him everywhere?”

“Having everyone contribute was really meaningful. We didn’t have strict rules around anything and that was to the benefit of the group,” said Creighton, who Zoomed in and blogged from Watertown. “The conversation just had a life of its own. It ran itself and was some of the smartest thinking and reading I’ve ever encountered.”

Lee, who helped Lynch organize the group, which numbered in the 30s throughout, specializes in British Romanticism and Asian American literature and has a long history of teaching “Clarissa.” But that didn’t prevent her from finding it “almost unreadable” this time around.

“I began teaching the abridged version in my ‘Rise of the Novel’ class. For a time, I even dreamed of teaching an entire course on the novel,” she said. “But after 2016, my feelings did a 180. I came to view it in a completely different light. I’m hardly able to read the letters from Lovelace, which make up a large part of the novel. Reading it after #MeToo, I’m not sure if I can teach it again.”

If the current social and political climate soured Lee on the plot, the global group of voices conversing virtually and through the blog brought her joy.

“As critics we often think about books alone and write alone, so to experience it as a group was enormously consoling to me. There were people from three continents, from Korea, Turkey, Ireland, Scotland, as well as from the U.S.,” she said. “In some ways the Zoom format made this reading group better than past ones I’ve been in. The simultaneous Zoom chats were also extraordinary, going at a mile a minute. Everyone occupied the same space, and it felt in some ways more intense and more equal than when you are physically present.”