Grooming behavior.

Credit: Liran Samuni/Kokolopori Bonobo Research Project

Differing diets of bonobo groups offer insights into how culture is created

New study focuses on neighboring bands of one of our closest relatives

Human societies developed food preferences based on a blend of what was available and what the group decided it liked most. Those predilections were then passed along as part of the set of socially learned behaviors, values, knowledge, and customs that make up culture. Besides humans, many other social animals are believed to exhibit forms of culture in various ways, too.

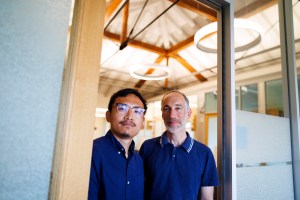

In fact, according to a new study led by Harvard primatologists Liran Samuni and Martin Surbeck, bonobos, one of our closest living relatives, could be the latest addition to the list.

The research, published today in eLife, is the result of a five-year examination of the hunting and feeding habits of two neighboring groups of bonobos at the Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve in the Democratic Republic of Congo. They looked at whether ecological and social factors influence those habits. Four of those years were spent tracking the neighboring groups of great apes using GPS and some old-fashioned leg work to record each time they hunted.

Analyzing the data, the scientists saw many similarities in the lives of the two bonobo groups, given the names the Ekalakala and the Kokoalongo. Both roam the same territory, roughly 22 square miles of forest. Both wake up and fall asleep in the bird-like nests they build after traveling all day. And, most importantly, both have the access and opportunity to hunt the same kind of prey. This, however, is precisely where researchers noticed a striking difference.

The groups consistently preferred to hunt and feast on two different types of prey. The Ekalakala group almost always went after a type of squirrel-like rodent called an anomalure that is capable of gliding through the air from tree to tree. The Kokoalongo group, on the other hand, favored a small to medium-sized antelope called a duiker that lives on the forest floor.

“The idea is that if our closest living relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, both have some cultural traits, then [it’s likely] our ancestors already had some capacity for culture.”

Liran Samuni

Out of 59 hunts between August 2016 and January 2020, the Ekalakala captured and ate 31 anomalure, going after duikers only once. Kokoalongo ate 11 duikers in that time and only three gliding rodents.

“It’s basically like two cultures exploiting a common resource in different ways,” said Samuni, a postdoctoral fellow in Harvard’s Pan Lab and the paper’s lead author. “Think about two human cultures living very close to each other but having different preferences: one preferring chicken more while the other culture is more of a beef-eating culture. … That’s kind of what we see.”

Using statistical modeling, the scientists found this behavior happens independent of factors like the location of the hunts, their timing, or the season. They also found the preference wasn’t influenced by hunting party size or group cohesion. In fact, the researchers’ model found that the only variable that could reliably predict prey preference was whether the hunters were team Ekalakala or team Kokoalongo.

The researchers make clear in the paper that they didn’t investigate how the bonobo groups learned this hunting preference, but through their analysis they were able to rule out ecological factors or genetic differences between the two groups. Basically, it means all evidence points toward this being a learned social behavior.

Martin Surbek.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

“It’s the same population, and it’s neighboring communities,” said Surbeck, an assistant professor in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology and the paper’s senior author. He founded and directs the Kokolopori Bonobo Research Project. “These two communities basically live in the same exact forest. They use the exact same places, but, nevertheless, they show these differences.”

The paper amounts to what’s believed to be the strongest evidence of cultural behavior in this primate species.

The researchers believe this paper is only the tip of the iceberg and are already planning the next part of the work: looking at how the bonobo groups learned these behaviors.

One of the main goals driving this work is helping characterize the cultural capabilities of the last common ancestor between humans and our two closely related great ape cousins.

“The idea is that if our closest living relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, both have some cultural traits, then [it’s likely] our ancestors already had some capacity for culture,” Samuni said.

Bonobos interacting in tolerant intergroup encounters in Kokolopori bonobos.

Credit: the Kokolopori Bonobo Research Project/Liran Samuni.

Bonobos can play a special role in this mystery. Like chimpanzees, which they are often mistaken for, bonobos share 99 percent of their DNA with humans. Bonobos are often seen as less aggressive and territorial, however, favoring sex in various partner combinations over fighting. Chimp groups, on the other hand, sometimes battle when they meet in the wild, occasionally to the death.

Different Bonobo population groups are known to interact and even share meals, which along with their socio-sexual behavior has earned them the moniker “hippie apes.” It’s those free love and peace traits that make them prime for this type of study since scientists can observe two neighboring bonobo groups to distinguish whether a behavior that differs between two groups that interact regularly comes about because of some sort of a learning mechanism (or social preference) or because the environment dictates it, the researchers said.

The authors of the paper were not much surprised by their findings.

They had noticed this hunting preference anecdotally, and it’s already believed that bonobos have subtle cultural traits. After all, a number of social animals display cultural behavior, especially when it comes to feeding habits. Chimps teach their young to use sticks to fish for termites. Dolphin mothers teach offspring to fit marine sponges to their noses to protect them as they forage on the seafloor.

What excites the researchers about this discovery, however, is that it shows the value of studying this often-overlooked endangered species and diving into its culture.

“They’re like the missing puzzle piece,” Surbeck said.

This work was supported by the Max Planck Society and Harvard University.