Nathan Pusey’s battle with Joseph McCarthy

Excerpt from new book recalls how college leaders sometimes defied and other times equivocated when faced with bullying demagoguery

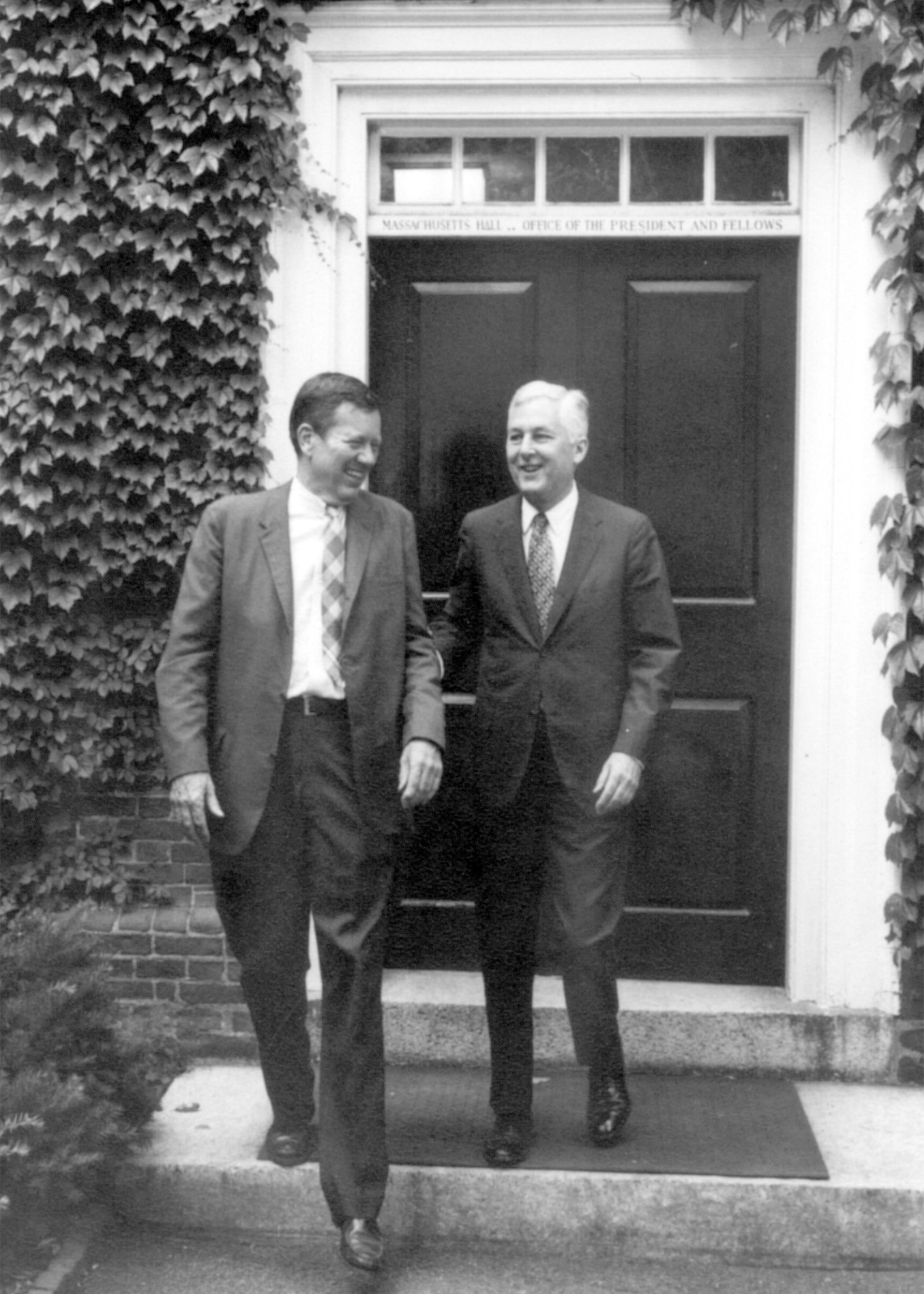

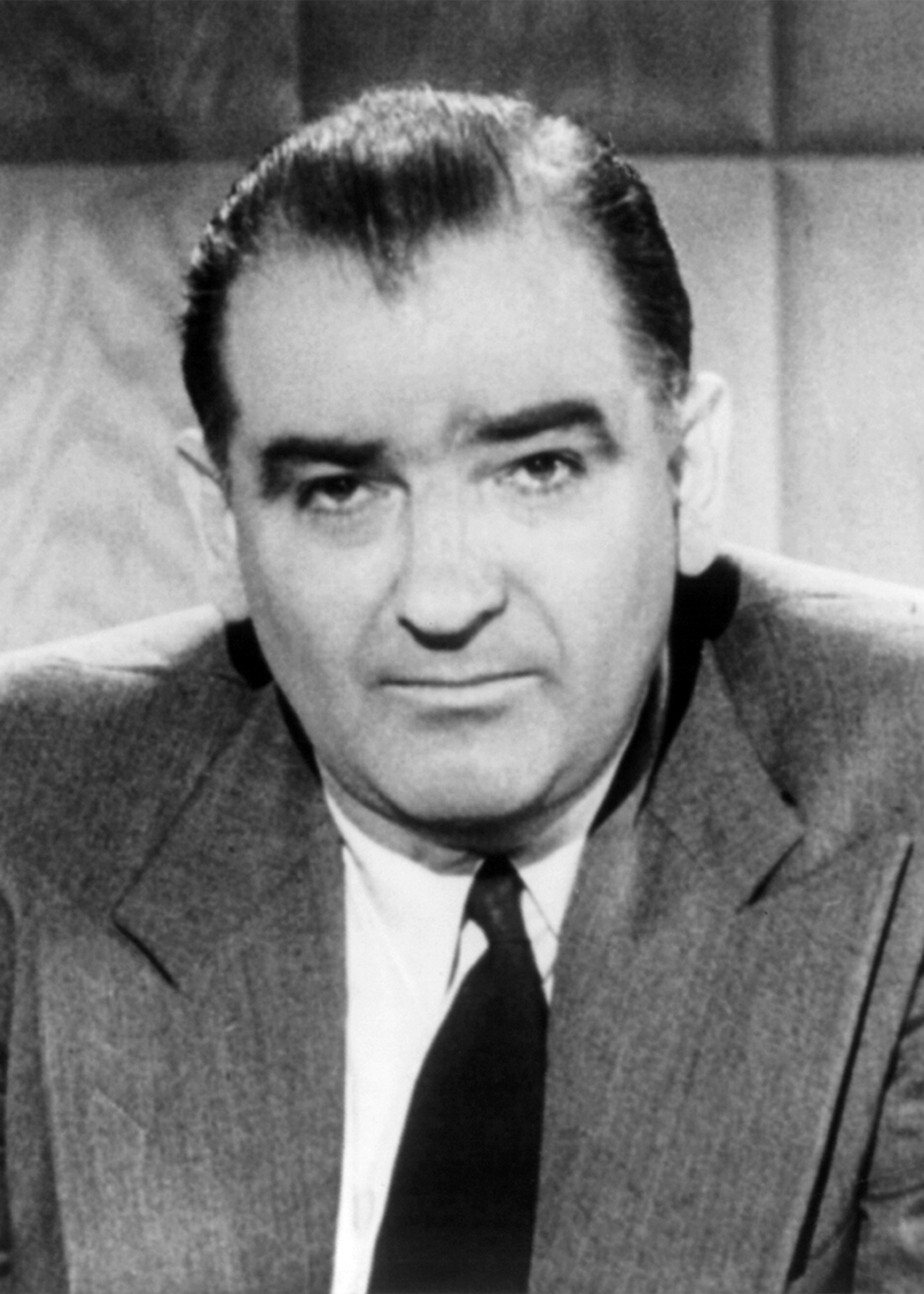

Nathan Pusey (right) had hardly been confirmed by the Board of Overseers in June 1953 when Sen. Joseph McCarthy took aim at him. Pusey is pictured June 30, 1971, his last day as Harvard’s president. McCarthy died in 1957.

The following is excerpted from the new book “Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy” by Larry Tye.

The fear-mongering and reckless accusations associated with Joseph R. McCarthy were said to have died with the senator half a century ago, but anyone paying attention today knows that the spirit of McCarthyism lives on. What is less well known is that Harvard University’s incoming president in 1953 was one of McCarthy’s favorite targets, with new records and interviews making clear that Nathan Marsh Pusey went further than most, if not as far as he might have, in defying America’s archetypal bully.

Pusey, who earned three degrees at Harvard in literature and history, was a devoutly religious Iowan, raised by a widowed mother on her $65-a-week salary as a school principal. When Harvard named him its 24th president, the 46-year-old Pusey was presiding over Lawrence University, a selective, under-appreciated college situated on the Fox River in Appleton, Wisc., McCarthy’s hometown and epicenter of support. The lawmaker and the academic had gotten along fine until Pusey endorsed “The McCarthy Record,” an anti-McCarthy tract published the summer before the 1952 election intended to expose and defeat its subject.

Joe was seething, but kept quiet until the following spring, when Harvard tapped Pusey to succeed President James Bryant Conant, another McCarthy foe. “Perhaps the best description of Pusey,” the senator said in a statement, “is that he is a man who has considerable intellectual possibilities, but who has neither learned nor forgotten anything since he was a freshman in college. He appears to hide a combination of bigotry and intolerance behind a cloak of phoney, hypocritical liberalism.” McCarthy continued in trademark phrasing that cloaked a condemnation in vindication: “I do not think that Pusey is or has been a member of the Communist Party. However, while he professes a sincere dislike for Communism, his hatred and contempt appear to be infinitely greater for those who effectively expose Communists … He is what could be best described as a rabid anti, anti-Communist … Harvard’s loss is Wisconsin’s gain.”

Pusey quickly learned that speaking out against Joe carried a cost with his supporters, as “invitations to speak stopped all at once. The Rotary Clubs, the PTAs, the Kiwanis Clubs, other colleges, commencements — they all thought I was some kind of a Communist.” Likewise, McCarthy hadn’t realized that Pusey, a staunchly Republican scholar, had built his own base in Wisconsin during his decade running Lawrence. Several editorial boards that had backed Joe split company here, including his own Appleton Post-Crescent, which wrote, “In stating that ‘I do not think Dr. Pusey is or has been a member of the Communist Party,’ McCarthy used a gutter-type approach. He could have referred as correctly to Pope or President.” A local paper company president who’d raised money for the senator telegraphed that this assault on Pusey was “uninformed and unadvised” and was “letting down so many old friends.” Pusey himself responded: “When McCarthy’s remarks about me are translated it means only: I didn’t vote for him.” His outspokenness against McCarthy won the heartiest accolades from the Harvard Corporation, helping seal his appointment as the first non-New Englander to head the nation’s oldest and wealthiest university.

The spat with Pusey was classic McCarthy. Policy was personal for Joe, and it was the handmaiden to power. Red-baiting was a fig leaf for elite-bashing. And the cleavage that mattered most in Appleton and much of America in the mid-1900s grew out of clashing world views — on one side, McCarthy’s Irish-Catholic, working-class Third Ward; on the other, Pusey and Lawrence University’s Anglo-Protestant, silk-stocking First Ward. So deep were the passions stirred that there were fissures even within precincts. “Arguments about McCarthy could split families and friends, even husbands and wives,” recalled John Torinus, an editor at the Green Bay and Appleton papers. “I remember at dinner parties we had to agree not to bring up the subject; it would just ruin the evening.”

The battle that began in Appleton carried over to Cambridge. McCarthy never liked the university that he blamed for training a disproportionate number of the foreign service officers at a State Department he viewed as a hotbed of Soviet subversion. Now the Wisconsin senator was seeking vengeance against left-leaning faculty members at Harvard, who he said were fair game for his subcommittee given the university’s lucrative contracts with the Department of Defense. What he didn’t say, but we know now from archives opened exclusively to this author, is that Joe’s investigators were digging up anything they could find on Reds at Harvard, with one list suggesting there were 75 or so “with [Communist-]front records.”

Caught in the crossfire were a physics professor and a social science graduate student, both of whom admitted to having been Communists, although neither still was, and both refused to name former comrades. “Each time he refuses,” McCarthy railed against Professor Wendell Furry, “he will be cited for contempt. This will be another way, perhaps, of getting rid of Mr. Pusey’s Fifth-Amendment Communists.”

Pusey cabled his reply in November 1953: “A member of the Communist Party is not fit to be on the faculty because he has not the necessary independence of thought and judgment. I am not aware that there is any person among the three thousand members of the Harvard faculty who is a member of the Communist Party. We deplore the use of the Fifth Amendment for the reasons set forth in the Corporation’s statement of May 20, 1953, but we do not regard the use of this constitutional safeguard as a confession of guilt. My information is that Dr. Furry has not been connected with the Communist Party in recent years. My information is also that Dr. Furry has never given secret material to unauthorized persons or sought to indoctrinate his students.”

It was vintage doublespeak — seeming to back Furry but only so far, defending yet deploring the Fifth Amendment, and accepting McCarthy’s premise on the per-se perils of communism even as the college president sought to lash back at the senator he hated. And it wasn’t just Harvard or Pusey that seemed to equivocate. Columbia, when Dwight Eisenhower was its leader (1948‒53) and afterward, along with many other universities, agreed that they wouldn’t tolerate Communists on their faculties.

At McCarthy’s insistence, Furry was indicted for contempt of Congress, although the case eventually was dropped. He was kept on by Harvard, and a decade later he chaired its Physics Department. Leon Kamin, the untenured grad student McCarthy targeted, fared less well. While he was acquitted of contempt, Harvard didn’t hire him. He found teaching jobs at Queen’s and McMaster universities in Canada, and when tensions eased a decade later he returned to the United States, chairing the psychology departments at Princeton and Northeastern. But the scars from Harvard and McCarthy remained. “It left me unemployable in the United States,” Kamin remembered in an interview shortly before he died in 2017.

As regards McCarthy, two things stood out for Kamin half a century later. “In the middle of testimony, he would always get up and say he had to go to the men’s room. And he would go down the hall to the men’s room and take out this brown bag and have another shot.” His alcohol consumption got so bad that “my lawyer, at the trial, couldn’t stand cross-examining him, because to cross-examine him as a witness you have to stand close to him, and he reeks of alcohol.” Still, Kamin acknowledged that McCarthy “had a certain charm … Once, I was walking down the corridor and he was coming back from one of those trips to the men’s room. And he threw his arm around me and said, ‘How are you Leon? Don’t take it personally, I’ve got nothing against you.’ I’m proud to say that I looked at him for a minute, because I had nothing to lose, and said, ‘[expletive] you.’”

“For a few short years in the late 1940s, the American people had more political options than they would ever have again. McCarthyism destroyed those options, narrowing the range of acceptable activity and debate.”

Ellen Schrecker, Yeshiva University

Back at Harvard, Pusey wasn’t the only one who alternatively stood up to and backed down from the senator. Arts and Sciences Dean McGeorge Bundy helped rid the faculty of Communists and fellow travelers, including a sociology graduate student named Robert Bellah, who admitted to having been a member of the Communist Party as an undergrad. Bundy, who later served as President John F. Kennedy’s national security adviser, pushed Bellah not just to name names to the FBI, but to get psychiatric counseling. “What all this amounts to is a record not of Harvard’s being a bulwark against McCarthyism, but of abject cowardice,” wrote Bellah, who went on to teach at Berkeley.

And he was far from alone in watching the crusade again communism unravel his career plans. Historian and Librarian of Congress Daniel Boorstin didn’t just apologize for his youthful communism, he named names. And across the country, there was an academic blacklist as insidious as, if less notorious than, the one in the entertainment industry. Professors who were fired, meanwhile, took jobs at historically black colleges desperate for Ph.D.’s, scrounged for work in lower-paying professions, or headed abroad, the way Kamin did.

McCarthy and McCarthyism’s precise body count is difficult to pin down, but Ellen Schrecker, a historian at Yeshiva University and specialist on the Red Scare, calculates that more than 10,000 Americans lost their jobs after being singled out as Communists or for refusing to cooperate with anti-Communist probers. For each who was booted, an estimated five to ten resigned in anticipation that they might be. Calibrating fear is harder, but Columbia University researchers tried in 1955, polling 2,451 college professors. Nearly half said they were scared of the witch hunts, a tally that rose to 75 percent among those who belonged to controversial organizations or were at a campus facing a crackdown.

“Marxism and its practitioners were marginalized, if not completely banished from the academy,” Schrecker said. “Open criticism of the political status quo disappeared. And college students became a silent generation whose most adventurous spirits sought cultural instead of political outlets.” Joe was delighted, warning that “we cannot win the fight against Communism if Communist-minded professors are teaching your children.”

“For a few short years in the late 1940s, the American people had more political options than they would ever have again. McCarthyism destroyed those options, narrowing the range of acceptable activity and debate,” said Schrecker. “From Harvard to Hollywood, moderation had become the passion of the day.”

Copyright 2020 by Larry Tye. Excerpted by permission of HMH Books & Media. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.