Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Home for dinner (and breakfast and lunch)

Classes were online, but home-cooked meals were right on the table

Pretty much every Harvard undergrad would agree that the sudden evacuation of campus in March due to the spread of the coronavirus was sad and unsettling. But most would also agree that the promise of savoring home-cooked favorites made the rushed homecoming a little easier. The Gazette checked in with students scattered across the globe to see exactly what they and their families have been cooking.

Craving the flavors of home

As much as Yousuf Bakshi ’23 enjoyed his campus life, he often craved the eclectic flavors of home. To Yousuf, it always seemed like whenever he would Skype home to Cardiff, Wales, the family would be sitting down for supper. “‘Look what we’re eating!’ they’d say.” Runa Bakshi, Yousuf’s mother, recalls waking up to text messages from her son that said, “All I want is a curry.”

Yousuf Bakshi’s first request when returning home in March was chicken curry, prepared by his mother.

Photo courtesy of Yousuf Bakshi

She and her husband, Nahed Bakshi, admit that their household “revolves around food” — and has for generations on both sides. Their families ran some of the first Indian curry houses in Cardiff. The restaurants served Bangladeshi-Indian favorites such as chicken pathia and tandoori chicken bhuna.

Over the years, the couple has developed different areas of specialty. Nahed is more experimental, delving into things like Asian-fusion dishes. He recently bought a fryer, to Yousuf’s delight. “For those days when all I’d like is an Annenberg grill order, my dad is always there to cook up some fries and make me a homemade pizza.”

Pizza and fries, Annenberg-style.

Photo courtesy of Yousuf Bakshi

Runa enjoys cooking a range of cuisines and has had the chance to share her dishes with a large audience. In fact, last year she was selected to appear in a popular British television cooking show, “Come Dine With Me.” In it, participants take turns hosting dinner parties and visiting the other contestants’ homes to taste their food. For her dinner, Runa prepared appetizers of chicken tikka satay sticks and meat samosas with mint sauce dip; a main course of Welsh lamb and potato curry, papadums, and tarka daal; and for dessert a deconstructed passion fruit surprise cheesecake. She cooked from 8 a.m. until 6 p.m., with judges and a full film crew filling up her kitchen.

In this episode of “Come Dine With Me,” Runa serves up a Bangladeshi menu.

She came in a very close second, with all the judges quietly sidling up to her to ask: “Can we have more samosas?”

Besides disrupting his School year, the pandemic also changed Yousuf and his family’s observance of Ramadan — the time “when we really start cooking,” his mother said. Big extended-family iftar meals, taken after a day of religious fasting, were canceled. Instead, the Bakshis exchanged dishes with family and friends by dropping them off at their houses.

Yousuf was busy writing papers and studying for finals during the majority of the monthlong holiday, but occasionally helped prepare some of the dishes. Each year, he looks forward to a staple Bangladeshi Ramadan rice dish, zaur, which also goes by the name kisuri. Pakoras, samosas, and chicken wings are some of the sides with which it pairs. Keeping with the family’s love of variety, some days the Ramadan table includes burgers or spaghetti.

The spread from a recent family iftar, the meal that breaks the fast during Ramadan, and three typical dishes.

Photos courtesy of Runa Bakshi

Now that Yousuf is finished with exams, his dad has a training program in mind for him. “We first need to introduce him to the essential spices: curry, coriander, cumin, turmeric, chili. Then the garam masala, cardamom, cinnamon sticks. Tomato paste and tomato puree.” Yousuf said he’s looking forward to learning to cook using his parents’ methods and recipes: “Quarantine is the perfect time.”

Obsessed with hummus

For Adam Sella ’22, food and cooking are inextricably bound to home and homeland.

His father, Uri, immigrated to the U.S. from Israel in 1994 and is the primary cook in the household. Adam was raised on Middle Eastern and Mediterranean dishes such as hummus, shakshuka, and kebabs, and over the years developed a deep interest in the cuisines through lessons from his father and from his own travels.

Before Harvard, Sella spent nine months living in Morocco, practicing Arabic, and cultivating his love for the region. Sella grew up visiting relatives in Israel, toggling between Hebrew and English. But he soon realized there was a third language that intrigued him. “In Israel, signs are posted in three languages; Hebrew, Arabic, and English” he said. “My dad lived his whole life not understanding the Arabic signs.” Sella wanted to be able to communicate, and his father was thrilled with his interest. Sella’s own taste buds also helped influence him: “In Israel, the best hummus is made by Arabs,” he said before backpedaling, “Well … there’s of course much debate about who makes the best hummus.”

Couscous is one of the recipes Sella has recently made at home in Cincinnati, cobbling together five different internet recipes. Though couscous is typically served with either all vegetables, or with meat like chicken or lamb, he used beef. (Whereas beef is expensive in Morocco, lamb is pricier here in the U.S.)

Couscous tfaya usually includes meat and chickpeas, covered with caramelized onions and raisins, topped with fried almonds and boiled eggs.

Photo courtesy of Adam Sella

Another family favorite is a slow-cooked beef and prune tajine — a kind of Moroccan stew named for the cone-shaped vessel in which it’s prepared.

A beef and prune tajine, one of the first dishes Sella made when he returned home in March.

Photo courtesy of Adam Sella

Even on campus during regular terms, Sella supplements meals in the Pforzheimer House dining hall with homemade extras. His friends sprinkle his homemade hot sauce on vegetables and meats. For the Jewish holiday Purim, he and friend Noah Singer ’22 made hamantaschen in a Pforzheimer hallway kitchen. For a few days, he carried around the cookbook “Zaitoun: Recipes and Stories from the Palestinian Kitchen,” after meeting with Director of Undergraduate Studies in Comparative Literature Sandra Naddaff, who recommended it.

Recently, his culinary interest even came in handy for a friend’s graduate school application. The application required that his friend teach a simple multistep process on video. Sella suggested his friend make tahini, by mixing tahini paste with the correct amount of water. Though it took a few tries to get the measurements down, the project was eventually a success.

But there are flavors Adam can’t seem to replicate either on campus or at home, so for those he turns to his father.

Uri Sella preparing fish tacos and shawarma.

Photos courtesy of Adam Sella

Uri Sella judges a good recipe by three criteria: cost, quality of ingredients, and amount of waste generated. The main mission of his culinary experiments comes down to a fascination with “how different cultures feed their people.”

“There are two things with being an immigrant here — always wanting to recreate the tastes of my home country — for example, an obsession with hummus. And then also being exposed to new cultures.” Uri has gone through significant phases of cooking Indian, Mexican, and Korean food. One day he’s making shakshuka, the next, curry.

Uri learned to cook primarily from family members and reading recipes, and now Adam learns from him. When his son was young, Uri said that Adam “would always come into the kitchen whenever he heard the sound of knives being sharpened.”

But now the two find themselves released from those roles. “I think my dad has delegated some of his exploratory cooking to me,” Adam said. For instance, when Adam returned home, his father handed him a cookbook of homemade pastas he’d borrowed from the library. “It was a subtle nudge for me to make some pasta.”

A glass of kefir a day

Living in Singapore, 12 hours ahead of her East Coast classes, Aline Damas ’20 had to adjust her eating, sleeping, and studying schedule. But there was one routine that remained the same: a glass of kefir in the morning.

Praised for its health benefits, kefir is a fermented dairy product similar to yogurt. On campus, Damas would start her mornings with a glass, a habit she owes to her mother.

“My mom’s a big fermentation person. I’ve become indoctrinated.”

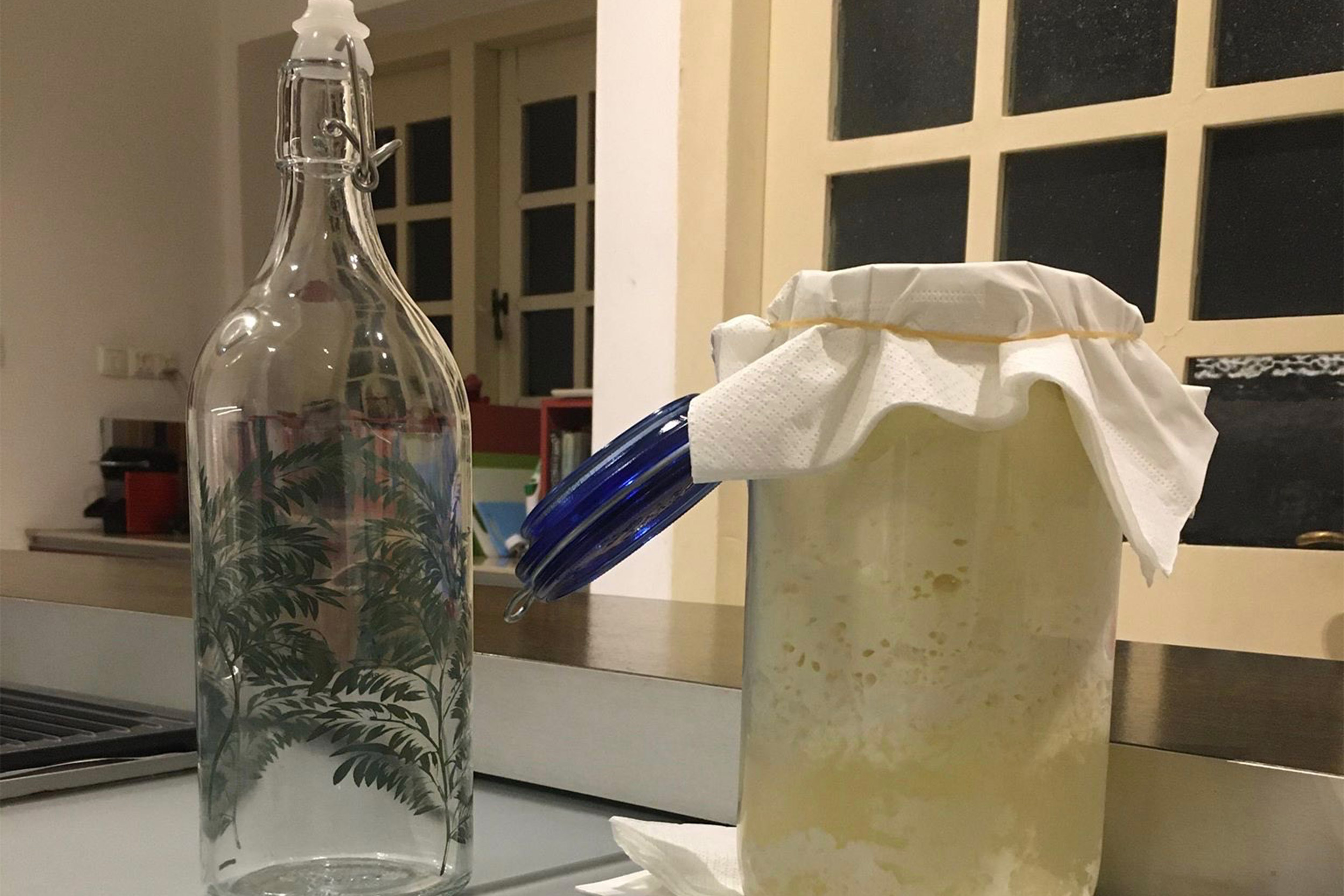

Damas’ mother has been making her own kefir since 2017. Each morning, she adds about a teaspoon of kefir “grains” (really a combination of bacteria and yeast) to a cup of milk. The mixture sits on the kitchen counter at room temperature for about 24 hours. By breakfast time the next day, it’s ready to drink, and she scoops out a small bit of the grains to use for her next batch, repeating the process.

Kefir fermenting in the evening. After the grains are strained away, it’s into a glass bottle, like the one on the left.

Photo courtesy of Aline Damas

Now that Damas is home, she also gets to include some of her mother’s fresh-pressed ginger juice in her kefir. Damas said that when her mother’s not making kefir, she’s brewing kombucha (another fermented beverage) or fermenting vegetables. Or she’s simmering chicken broths and bone soups.

“My mother has always been interested in health, but over the last few years it has really intensified,” Damas said.

Alongside these incorporated recipes, the Damas’ family meals have two main origins: French (Damas’ father is Belgian), and Asian, the continent where Aline and her brother grew up. For the French side, Damas cooks “lots of ratatouille, steak au poivre, and piperade [sautéed green pepper stew].” For the Asian side, the family often eats takeout Thai and Chinese.

Damas said cutting out processed sugars from her diet has made her feel healthier. When she does eat something sweet, she sticks to fresh fruit and raw honey, though there is the occasional treat. “I do indulge in 80 percent dark chocolate every now and then.”