Juneteenth in a time of reckoning

Emancipation Day celebration, June 19, 1900 held in “East Woods” on East 24th Street in Austin, Texas.

Photo courtesy of the Austin History Center, Austin Public Library

Members of the community share memories, plans, hopes for the holiday

Celebrated annually in the African American community but unfamiliar to many other communities, Juneteenth commemorates the end of slavery across the nation, with the last piece falling into place when the Union Army took official control of Texas on June 19, 1865, more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation. Now it is recognized as a state holiday in 45 states and Washington, D.C. Efforts to make it a federal holiday have been unsuccessful. This year’s celebration, however, comes amid continuing protests and a national reckoning with the legacies of slavery and racism, triggered by the police killing of George Floyd. To understand the significance of Juneteenth, a blending of the words June and 19th, we asked some members of the Harvard community what the holiday means to them.

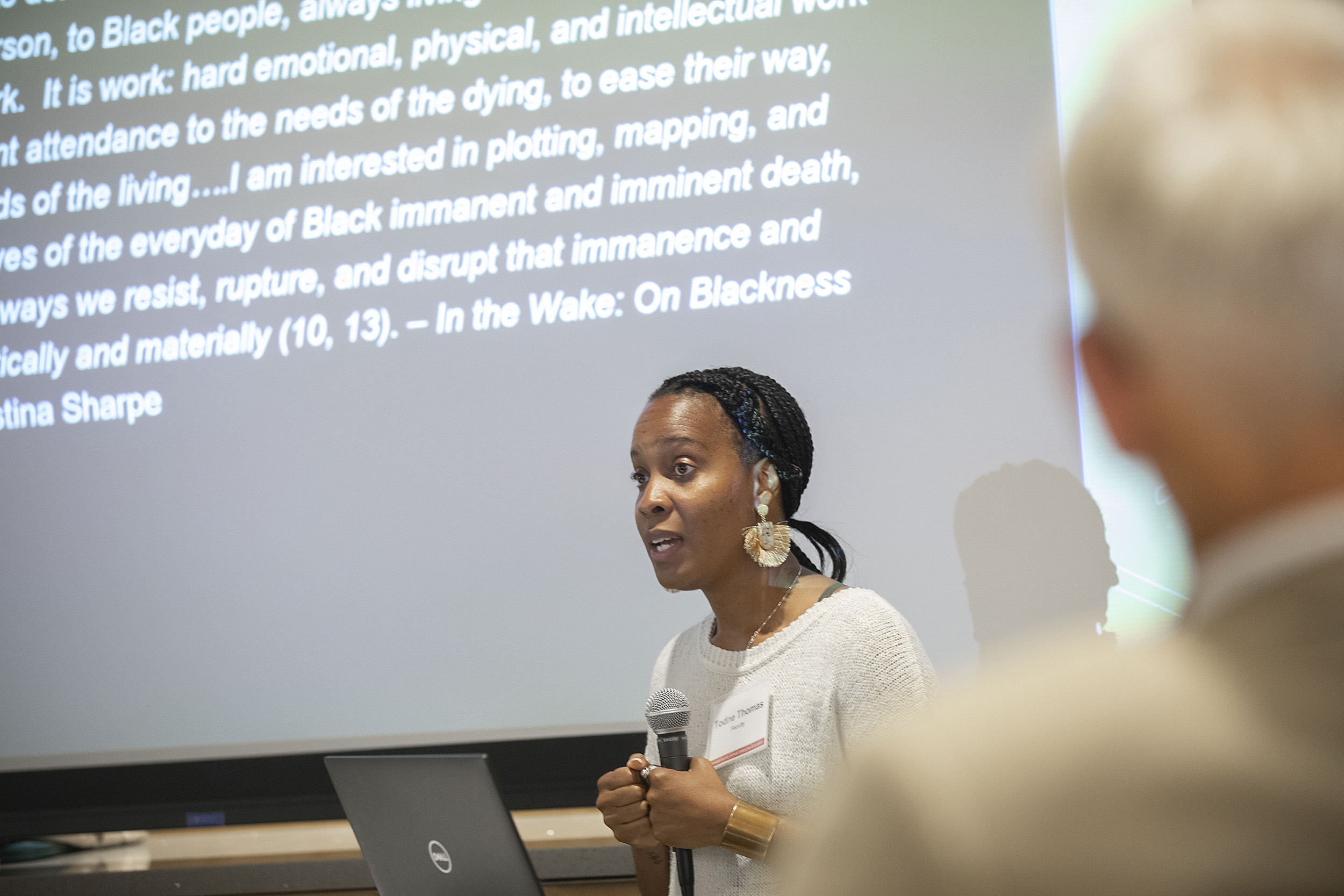

Todne Thomas

Assistant Professor of African American Religions at Harvard Divinity School; Suzanne Young Murray Assistant Professor at Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

As we are situated between the recent pandemic of COVID-19 and the sustained pandemic of anti-Black racism, Juneteenth is now entering the limelight as a holiday that may be on the brink of national observance. As an Affrilachian anthropologist conducting research on Black church arson in Knoxville, Tenn., for me Juneteenth often takes a backseat to the emancipation holiday of Aug. 8. Referred to as “the eight of eight” in local parlance, it commemorates the day that [then-Tennessee military governor and later president] Andrew Johnson freed enslaved people whom he had held in bondage in 1863. [A year later he would free all the rest of the enslaved individuals in the state.] Since 1863, it’s been celebrated in Tennessee and is currently under consideration as a state holiday. As a scholar tasked with illuminating lived phenomena from the bottom up, I confess I am more inspired by the stories-within-the-stories of Juneteenth and Aug. 8. I am more interested with the self-liberation and collective acknowledgments of freedom celebrated by the formerly enslaved rather than the official readings or granting of freedom by the state or slaveholders. I am excited about the thickening archive of stories that depict how African Americans inhabited and commemorated their freedom. And in this moment, I am particularly curious about how the contemporary descendants of the enslaved like myself will make meaning of the fact that their ancestors’ abolitionist efforts were victorious.

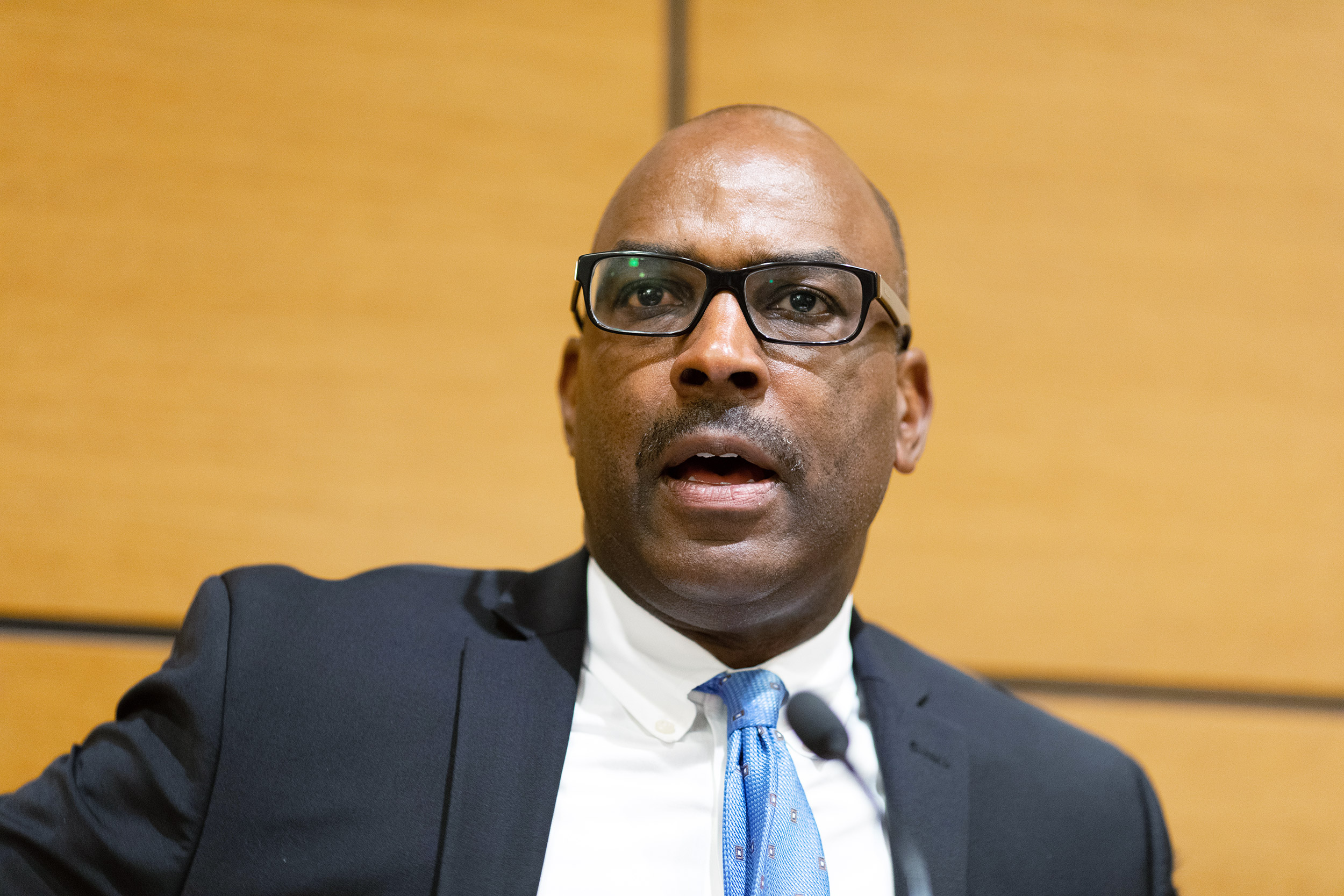

David Harris, Ph.D.’92

Managing Director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School

Photo by Lorin Granger/Harvard Law School

Juneteenth is a defining day. However empty the promise of freedom often appears to have been, Juneteenth has remained a day uniquely celebrated by the descendants of the formerly enslaved. Its importance far outweighs any other secular holiday, and its celebration carries with it a special, unique quality. In a nation that consistently fails to educate us or uses education to misguide us, Juneteenth is our rendering of history; it is an active assertion of our determination to be free. We come together, perhaps this year virtually, but powerfully nonetheless, in community.

Indeed, we come together to assert what years of enslavement attacked but could not destroy: our incredibly strong bonds of family, friendship, and fellowship. We use the day to pass along family and community history in the midst of good food and good cheer. There is song and dance and storytelling, and it is thus that we affirm ourselves.

Samantha O’Sullivan ’22

Joint concentrator in physics and African American studies; co-founder and president of the Generational African American Student Association

Photo courtesy of Samantha O’Sullivan

I was never really taught about it in school. I learned about it a few years ago when I read about it, and since then it has meant a lot to me. It symbolizes independence for African Americans in this country. It also made me realize the irony in the celebration of the Fourth of July because we celebrate American independence, and yet there were many people who were not independent or free. I now view Juneteenth as the true Independence Day, because that was the day when all Americans got their freedom.

It’s really great that Juneteenth is gaining national attention. It shows that people are finally waking up to our lived reality in this country and our experience and struggles. Hopefully, it’ll become a federal holiday. Last fall, a group of students and I founded a student group, the Generational African American Student Association (GAASA), and one of our goals was to celebrate Juneteenth as a sort of African American Independence Day to educate the Harvard community. We’re organizing a virtual celebration on June 19 at 7 p.m. EST. It’ll be educational but also a celebration. My family plans to cook a big meal.

Opeoluwa Falako ’22

Concentrator in African and African American Studies and molecular and cellular biology; president of the Harvard Black Students Association

Photo courtesy of Opeoluwa Falako

A simple Google search will tell you that Juneteenth is a holiday that marks the end of slavery. However, the actual meaning of the day is so much deeper. It represents the first few steps away taken by Black people from captivity and toward equality in this country. Although the first Juneteenth happened over 100 years ago, Black people are a long way from feeling true equality, as we have to deal with the oppressive practices that plague American society. The protests in reaction to the slaying of George Floyd at the hands of the police and the overall Black Lives Matter Movement is a direct response to these oppressive systems. It is important that holidays like Juneteenth exist not only to celebrate how far we have come but to also demonstrate that we still have a long way to go. The celebration must go beyond the Black community, however. There should be more widespread education about the significance of Juneteenth and other important moments of Black History by our non-Black peers; only then can we, as a society, collectively continue on the path to equality for Black people.

Kenneth Mack

Lawrence D. Biele Professor of Law at Harvard Law School; affiliate professor of history at Harvard University

Photo by Lorin Granger/Harvard Law School

I didn’t grow up with Juneteenth. As we know, the holiday originated in Texas and spread through other communities through migrants from Texas. In the place I grew up, Harrisburg, Pa., we didn’t celebrate Juneteenth.

I first heard about Juneteenth as an adult from friends who had lived in the South or closer to the places where Juneteenth has been traditionally celebrated. But when I heard about it, it certainly resonated with me. There are gatherings of African Americans all over the country that celebrate forms of autonomy, where things that might look like recreational activities, picnics, etc., in fact are assertions of autonomy in a world in which African American lives are devalued.

When I grew up in the 1970s and ’80s, there were many Black Americans who had never heard of Juneteenth. Part of the reason is that Juneteenth has been a celebration that occurred within certain Black communities. The communities of white Americans that surrounded them often were not paying attention, and that is probably one of the major reasons why Juneteenth is unknown to most white Americans.

I’d be in favor of starting a conversation about making Juneteenth a national holiday. But to get Martin Luther King’s birthday to be a national holiday was a very long and complicated struggle that was resisted on the federal level and on the state level, and it’s still resented in some quarters. And secondly, I’d say that there are a number of reforms that have been proposed growing out of the killing of George Floyd that would be more protective of Black lives and Black aspirations, and those probably should come first.

But the reason why we should at least consider it is that we don’t have a celebration of emancipation. We have the Martin Luther King birthday, which is an incredibly important celebration of a particular time and of the person who, with many others, was part of the movement that helped eradicate Jim Crow and make America modern, in terms of race. The centuries of slavery in North America, the long struggle to abolish it, the dehumanization of human beings under that institution, and the push headed by both Black and white Americans to come to grips with that problem don’t have a national commemoration. We commemorate Abraham Lincoln in various ways, but we don’t have a national commemoration of the triumph over slavery, which has to be one of the most important moments in American history. One should consider Juneteenth in that context. The best case to be made for Juneteenth would be as a commemoration of both the legacy of slavery and the success of the movement to abolish formal slavery in the United States.

Jeraul Mackey ’21

Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Ph.D. student; member of the W.E.B. Du Bois Graduate Society Steering Committee

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

I knew about Juneteenth growing up in New Orleans. We didn’t celebrate it the way you would celebrate Christmas, but friends and family would say, “Happy Juneteenth” to each other. But as I got into institutions that are predominantly white, the history of Juneteenth was not there or as salient as it was when I was growing up.

To me, what is important about Juneteenth is that we’re not celebrating the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, but instead we celebrate the change in the material conditions of folks on the ground, when the last enslaved people in the country became free.

Now that many corporations are embracing this holiday, which is very much a Black holiday, it makes me wonder whether they are willing to do more than putting up a press release full of platitudes, or take actions to improve the lives of those who live on the margins of society. The story of Juneteenth tells us that 2½ years after the Emancipation Proclamation, Union officers arrived in Galveston with the news. But we know that plantation owners knew that enslaved Africans were free long before the Union officers showed up in Galveston. The story is a reminder of how those who claimed ignorance perpetuated the exploitation of Black people for their own benefit for 2½ years, a period in which many folks were terrorized, tormented, and maybe even killed.

I see this Juneteenth as an opportunity for folks within and across the diaspora, as well as individuals outside of it, to understand the importance of the holiday. It’s not only a chance to look back at history, at the life and experience of Black folks whose ancestors came here as chattel, as enslaved Africans; but we should also reflect on how that history connects with the moment we’re in now, and remember what Martin Luther King Jr. said, “No one is free until we are all free,” and that we’re in this struggle together.

Tommy Amaker

Head coach, Harvard Basketball

Jon Chase/Harvard file photo

It is important that we acknowledge and celebrate the significance of Juneteenth. It is one of the more meaningful dates in our nation’s history. It should always be a day we all reflect on our journey to become a more just and fair society — in every way.