Photo by Daniel Schwen

Gateway City: Viewed as an intersection of slavery, capitalism, imperialism

Historian Walter Johnson sees history of St. Louis as emblematic of the schisms in America

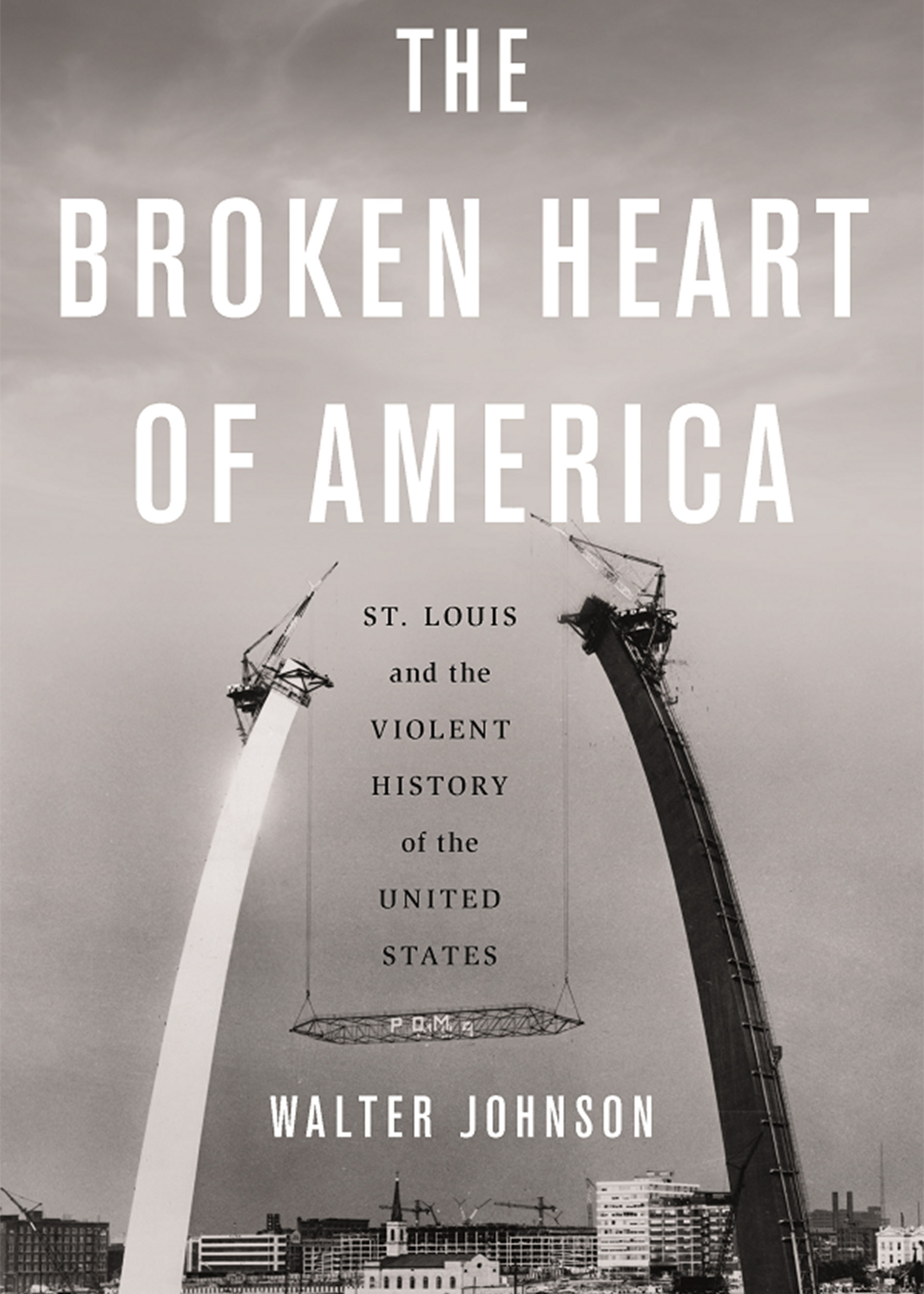

Slavery, capitalism, and imperialism in American history are central to the work of Walter Johnson, the Winthrop Professor of History and Professor of African and African American Studies at Harvard University. In a new book, “The Broken Heart of America: St. Louis and the Violent History of the United States,” the Missouri native shows how those themes — and a spirit of rebellion — come together in the story of the Gateway City. The Gazette recently spoke to Johnson about his inspiration for the book and St. Louis’ importance in American history.

Q&A

Walter Johnson

GAZETTE: St. Louis today often is overshadowed by other large cities, but you see its story as central to the American experience. How so?

JOHNSON: I see St. Louis as a place that has produced a lot of the history, including enduring traditions of both racism and resistance, that we think of as American history. I’m talking about things like the Missouri Compromise, or the Dred Scott decision, or the first general emancipation in the history of the United States, the first truly successful general strike, the sit-in movement, all of these are things that originated in St. Louis, and things we think about as American history. So part of what first drew me to the history of St. Louis was just recognizing the kind of pattern of events there and the way people had thought about these as American history without really trying to place them in the specific context of St. Louis.

GAZETTE: How do you define “racial capitalism” — a term you use in your book — and why do you think it is so crucial to understanding the story of American race relations?

JOHNSON: The way that I think about racial capitalism is in dialogue with a tradition of thought dating back to W.E.B. Du Bois. The idea is that there is a dialectical relationship between capitalist exploitation and racial domination, that the two things have been intertwined since 1492, or since the era of Atlantic empires, that the exploitation has been justified by notions of proto-racial and racial difference, and that the relationship has then created novel notions of difference. So what I try to chart in the book is a series of those kinds of racial capitalist formations, the way exploitation is justified and shaped by notions of difference, and how those patterns of exploitation then lead to the ossification and the deeper sedimentation, the materialization of differences between differently racialized groups.

As an example, a housing-segregation ordinance profits landlords by creating a market where white people pay extra to live on one side of a line, and black people are increasingly confined to an ever-shrinking patch of ground, and thus have to pay more and more in rent. So profits are wrung out of people through racialization. But then there is a kind of second-order racialization where those on the white side begin to feel superior because the objective conditions of their lives are more comfortable. To understand that, they begin to associate blackness with a kind of social precarity, and a kind of a degraded condition of life — beat-up houses, outside toilets. So there’s both a pattern of exploitation feeding off notions of difference and then the history of exploitation shaping people’s lives, getting sedimented into social lives, even into people’s bodies as a shortened life expectancy.

GAZETTE: How was the racism that became endemic in St. Louis in the 19th century different from how it functioned in the South?

JOHNSON: There is a particularly Western form of anti-blackness that emerges out of the imperial crucible of St. Louis. From the era of Indian removal, a large portion of the white population of St. Louis and large parts of the Midwest were non-slaveholding whites. These white families were immigrants from places like Virginia where they had felt politically and economically exploited by the slaveholding class. So they migrated west, aspiring to getting out from under the white slaveholding class. And the way they conceptualized their pathway forward was finding the freedom of a white man’s country, a place without black people — without enslaved people, whom they viewed as the cause of inequality between whites, but also without free people of color, whom they viewed as labor competition. What I try to chart in the book is how the notion of an ethnically cleansed West was transferred from the project of Indian removal into different forms of the control and removal of free black people, in particular in St. Louis.

In his new book, historian and Harvard Professor Walter Johnson opens up the Gateway City to scrutiny.

Photo by Alison Frank Johnson

GAZETTE: You suggest that particularly in St. Louis and the West, the persecution of blacks and Native Americans is really part of the same story.

JOHNSON: I do see those two stories as very interconnected, though not identical. So for instance, you can see the connection in the career of William Harney, the U.S. military officer who murdered an enslaved woman in St. Louis in 1834 and then went on to a career as one of the most bloodthirsty Indian killers in the United States Army. It’s also true that there are moments at which the two stories come into contradiction. Some of the most forthright advocates of emancipation and perhaps even black freedom in the Civil War were themselves Indian killers and imperialists. And so somebody like John Frémont is a very complicated character for me, or somebody like Gen. Nathaniel Lyon, because both went, I think, as far as white military men went at the front edge of the struggle for black freedom during the Civil War, and yet both of them were by any modern standard war criminals.

GAZETTE: Your book is also about how people in St. Louis have long fought back against inequality. What inspired you to emphasize that part of the city’s history?

JOHNSON: Once I started to look into what I saw as the deep history of structural racism in St. Louis I found something I hadn’t initially thought to look for: a very deep history of radicalism — not just a history, but a tradition. I found people drawing on the example of past struggles as they sought to confront the injustices in their own lives. That story really starts with the Indian Wars of the 1830s, and then follows through people like Dred Scott, or different free people of color and enslaved people who rebelled in various ways in the antebellum period. And then the real inflection point for me is the Civil War, where there was an extraordinary alliance between German-speaking European radicals and the revolutionary group of escaping enslaved people. And I try to follow that history up through the extraordinary strike at Funsten Nut in the 1930s led by black women, supported by the Communist Party in St. Louis.

You can trace it all the way up to Ferguson. I like to tell people the story of an employment action in 1963 outside Jefferson Bank. This was a bank where a lot of African Americans in St. Louis had their savings, but which employed no African Americans. One of those walking that picket line was Hershel Walker, a black communist who had been chairman of the Communist Party in St. Louis in the ’40s. Along with him was Percy Green, who would become one of the most notorious Black Power activists in St. Louis in the ’60s and early ’70s. He was a figure in CORE [Congress of Racial Equality] and then ACTION [Action Committee to Improve Opportunities for Negroes] and then was one of the sort-of godfathers of the Organization for Black Struggle, which was run by an activist, Jamala Rogers. Many Ferguson activists came out of that organization, including Tef Poe. So you have a story that links Tef Poe on the street in Ferguson to Jamala Rogers, also active in Ferguson, to Percy Green, to Hershel Walker.

“Once I started to look into what I saw as the deep history of structural racism in St. Louis I found something I hadn’t initially thought to look for: a very deep history of radicalism — not just a history, but a tradition.”

GAZETTE: How do you see the historic themes you trace in your book — racism, imperialism, rebellion — playing out in Ferguson and St. Louis today?

JOHNSON: My interest most immediately in Ferguson was with political economy and what I would call structural racism. It was in tracing back the long history of the encounter between Michael Brown and Officer [Darren] Wilson on Canfield Drive and figuring out how you can have a city that is home to the headquarters of a $26 billion-a-year corporation, Emerson Electric, but is farming poor black motorists for traffic tickets to keep its books balanced. And then to see that situation as the framing cause of the confrontation on Canfield Drive. You can trace that moment forward into attitudinal racism — the way police treat people — but you can also trace it historically backward, to ask where did these conditions come from, why do we have a city resorting to what is basically a medieval model of revenue production. So the book tries to talk about the construction, both in the immediate sense — such as the construction of the city’s infrastructure — but also metaphorically, the historical building of social relationships within that city, to see why it is that St. Louis looks the way that it does and what sorts of policing and predation and resistance and aspiration have shaped that.

GAZETTE: You say that racism is built into the material fabric of the U.S. and that we can’t grapple with economic inequality without changing that. So where do we begin?

JOHNSON: Racial difference, racial exploitation, and racial privilege are built into the material fabric of our lives. Some see a one-size-fits-all material solution to that, whether it be a one-size-fits-all notion of the rising tide of the market lifting all boats, or a one-size-fits-all socialism, which argues that all of these things are really at root of class differences and so if we just address economic inequality everything will be OK. I’m trying to address both of those arguments. The material inequality in the society can only be addressed with particular attention to its differential effects. I’m particularly concerned in this book with the different effects of imperialism, social marginalization, class marginalization, and racial marginalization. It’s really a plea for a particularly rigorous accounting of the way that the history of the United States has produced a kind of a sedimentation of racially stipulated inequality.

Interview was edited for clarity and condensed for length.