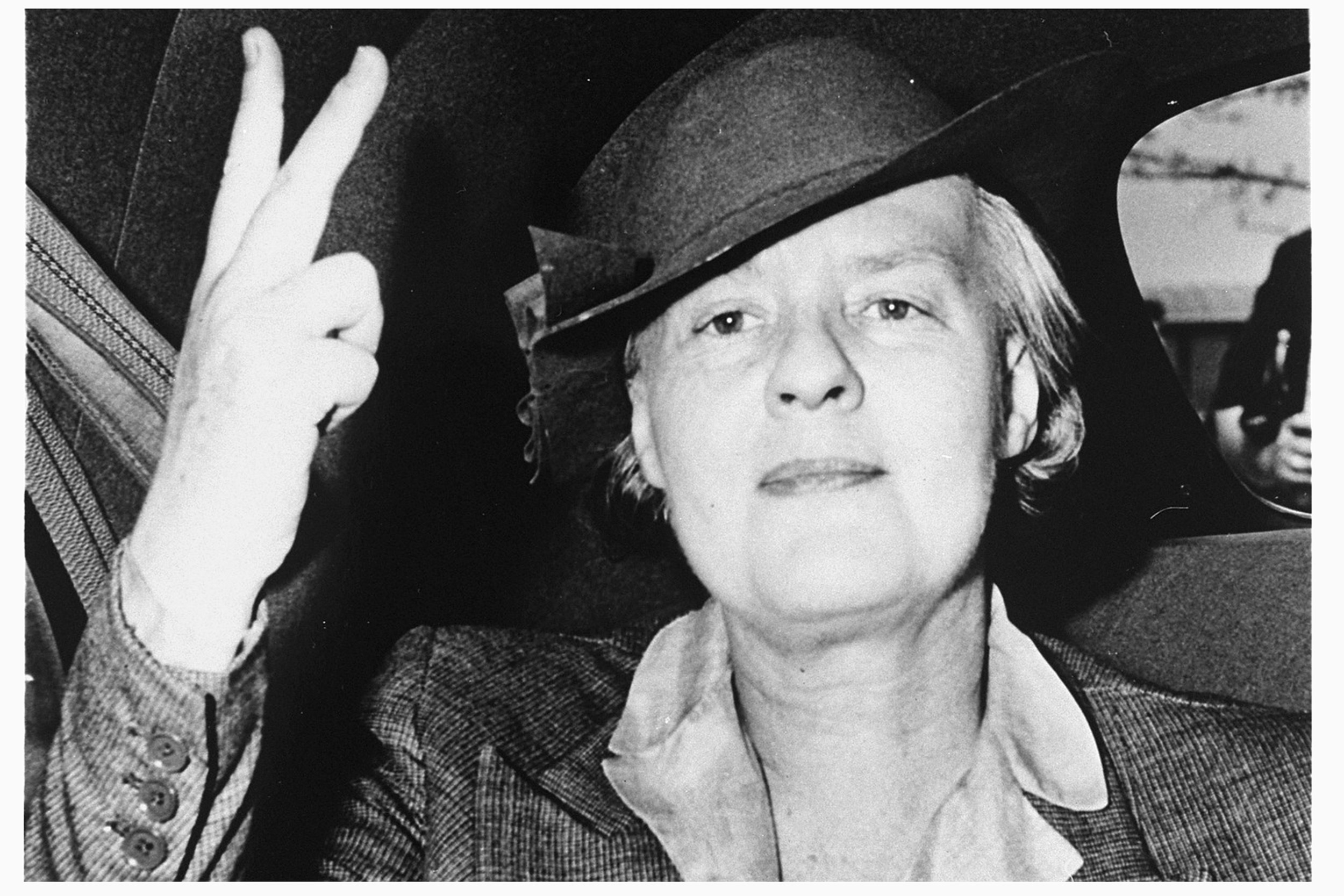

Dorothy Thompson is one of four journalists written about in Nancy Cott’s new book. Thompson is pictured circa 1940. The image is held by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park

Reporting on the world between the wars

Historian Nancy F. Cott tells the story of the period through the lives of four American foreign correspondents

The years following World War I were a time of uncertainty, upheaval, disillusionment. Many young Americans left behind the comforts of home in search of adventures and answers abroad. Among them were journalists who tried to make sense of a world so utterly changed, even the borders of much of it were no longer familiar. It’s these journalists whom historian Nancy F. Cott focuses on in her new book, “Fighting Words: The Bold American Journalists Who Brought the World Home Between the Wars.” Cott, the Jonathan Trumbull Professor of American History, studies the work and lives of four of them at a time when authoritarianism and facism were beginning their creep across the ruins of the old international order. The former director of the Schlesinger Library at the Radcliffe Institute, Cott is the author of six previous books, including “Public Vows: A History of Marriage and the Nation.” She spoke with the Gazette on her latest and what parallels she sees between then and now.

Q&A

Nancy Cott

GAZETTE: The book centers on the work of four American journalists abroad between World War I and World War II. Can you tell us who they were and a bit about each of them?

COTT: The short version is that they were young and restless Americans who each went recklessly abroad and reinvented themselves as international journalists while living very tumultuous personal lives. Dorothy Thompson was a woman who went abroad with vague intents, but with a clear hope that she would break into journalism. She quickly became a foreign correspondent and made quite a name for herself in Central Europe. In fact, Thompson was the first American journalist expelled from Nazi Germany for her reporting and came home to become one of the nation’s first “op-ed columnists” for the New York Herald Tribune. She was probably the most consistent anti-fascist voice in America in the ’30s.

Then there was Vincent Sheean, who became a friend of hers because they met in Europe, but was a different type of person: a freewheeling Catholic boy who spoke numerous foreign languages and went to Paris, where he got a reporting job with an American newspaper. It didn’t last. He became so politically passionate about opposing European imperialism that he dropped it because he did not want to be an objective journalist, so he made his way as a more opinionated freelancer through the later 1920s, ’30s, and into the ’40s.

His friend, John Gunther [also from Chicago], had in certain ways a similar career. Gunther dabbled in newspapers at home first and then managed to sort of nerve his way into becoming a foreign correspondent when he was about 24 for the Chicago Daily News, which had a very important foreign service, and did that until he was 36. After, he gained even more renown as a writer of books about foreign affairs. He, Sheean, and Thompson had lots of ups and downs in their personal, marital, and sexual lives.

Finally, my fourth character is an even-less-known woman, Rayna Raphaelson, who left the United States after her marriage fell apart. Raphaelson’s career was different in that she went to China, not to Europe, where she became enmeshed in the Chinese Nationalists’ struggle and worked for the revolutionary Guomindang [Nationalist party].

Historian Nancy F. Cott looks to four international journalists in her new book, “Fighting Words: The Bold American Journalists Who Brought the World Home Between the Wars.”

Harvard file photo

GAZETTE: What drew you to write a historical account of international journalists during the 1920s, ’30s, and part of the ’40s?

COTT: I started off wanting to write a book about the youthful generation of the 1920s. My previous book had been about marriage and the state, involving a lot of legal cases and lots of government documents. This time, I wanted to write a book driven by the narratives of real individuals. I started reading a large number of biographies and autobiographies of people who were young in the 1920s, and I was struck with how many of them went abroad. It was not something I expected to find, and it’s a point I want people to take from my book: There was a lot of global searching by this generation who had inherited a destroyed world after World War I. So, I started looking more and more in detail into some of their lives and I decided that in order to make my book go where I wanted it to, I needed to have some organizing theme. I chose journalism because, again, I discovered just how common a pass abroad that was for many young people who were smart, had a way with words, and had some education — which all four of these subjects did.

GAZETTE: In the book, you explore how Thompson, Sheean, Gunther, and Raphaelson pursued international headlines while you make it a point to delve deep into their personal lives, including their marriages and many romantic and sexual affairs outside of them. Why was that important?

COTT: I see this as a newer principle of historical writing, influenced by women’s history and gender analysis, insisting that people’s personal and public lives are always intertwined. It’s not typical in historical writing, except in biography. I think that one has to look at the public accomplishments in view of the personal life. In part, this is because no one accomplishes what he or she accomplishes alone. The other people in that individual’s life are always contributors. Sometimes they’re positive contributors. Sometimes they are negative contributors. I think Dorothy Thompson’s travails with her husband, Sinclair Lewis [who was one of the most famous novelists of the time], because of his alcoholism, did not advance her professional aims. Yet, there were other features of her association with him, especially his very great fame, that did. These things have to be recognized. I also think that the opinions of those one is with intimately, or in friendship networks and social networks, are influential in terms of opinions that may be expressed professionally. They certainly were for these people. These things are relevant; they’re part of the historical data one should be consulting when writing about any individual. Bringing the two together is important.

“There was a lot more nonmarital sex and adultery in this generation of young people from the 1920s and 1930s than is recognized; it has never really been looked at as a generational phenomenon.”

GAZETTE: Did your subjects reflect certain trends from that youthful generation you wanted to look at? If so, what were they?

COTT: To an extent. In their generation there was a minority of cosmopolitan-minded, international-minded people who paid attention to social, cultural, and political emanations from other parts of the world. In that sense, I think these people do represent that very important and large minority of their generation; and also in their freewheeling sexual lives. There was a lot more nonmarital sex and adultery in this generation of young people from the 1920s and 1930s than is recognized; it has never really been looked at as a generational phenomenon. It seems to me — although I’m risking a generalization here — that in the stratum of the socioeconomic population my subjects represent (they might be called the aspiring middle class) there was a lot of sexual experimentation, since sexual adventure is part of what it meant to be modern at that time, and that the clampdown on sexual so-called social deviance in the post-World War II period changed that.

GAZETTE: At this particular moment in history, why was the work of international correspondents so important?

COTT: The participation of the U.S. in World War I changed the nation’s orientation toward the world. American commercial policy, American industry, and American business had been international for at least 100 years by that time, but the U.S.’s position in international foreign relations wasn’t large or that influential. The position that the U.S. assumed during World War I — saving the Allied side with its supplies and its soldiers — was very, very important in making the United States a player on the world stage in a way that it had never been before, especially because it was economically positioned after the war so much better than any of the other former belligerents. (Also, a lot of war debt was owed to the U.S.) It was clear that the U.S. was going to have a position in international relations that it could not avoid, but the big question was whether culturally and even informationally, the U.S. population was up to speed with that. Some were, but I would say probably more than half were not, and so it took the prime information agency of the day, which was the press, to get the American public to see that this was an age of speedy transportation, and communication, and that just having an ocean on each side did not insulate us from involvement in quarrels and potentially wars that took place on other continents. The U.S. had international responsibilities and had to figure out how to or if to take these on.

GAZETTE: That echoes a bit today. From your research and looking at this particular point in American history, are there any other parallels laid out in the book?

COTT: Yes, the first, which is perhaps the most disturbing, is the one between the world’s political situation then and now in terms of the ability of authoritarian leaders who have popular support to take over in many important countries and destroy democratic institutions, especially representative parliaments. When I began this book, of course, I was aware of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, but I really did not know how many countries in Central Europe had been taken over by authoritarian leaders — some who by the 1930s were fascists. It was really striking that by the mid-1930s many European countries had an authoritarian or fascist leader. It wasn’t just Italy. It was Austria. It was Hungary. It was Yugoslavia. It was Poland. That’s all to say, the question — will democracy survive? — was on the table from the late 1920s into the 1930s. Today, with countries like Poland, Hungary, Brazil, and India sliding toward authoritarianism, I think it’s becoming a question as well.

Secondly, international journalists then, including the ones in this book, by making it a major issue that Americans had to be concerned about these failings, showed that Americans could not take their constitutional system and its continuation for granted. I think that’s very true today, too.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. “Fighting Words: The Bold American Journalists Who Brought the World Home Between the Wars” is available in stores and online .