Was Darwin first? Kind of depends

Arboretum Director Friedman discusses evolution’s forgotten ancestry

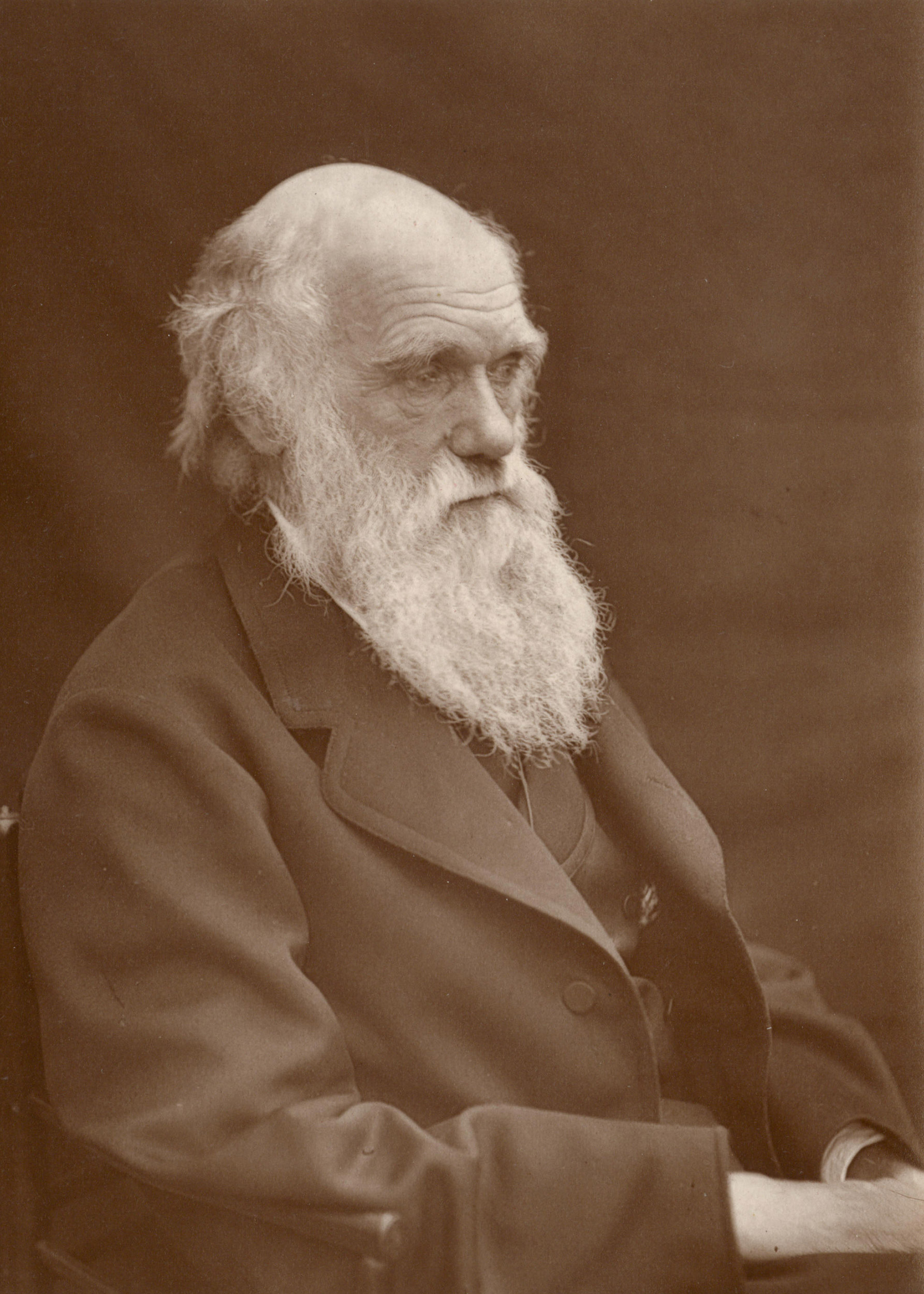

Photograph of Charles Darwin taken around 1874 by Leonard Darwin.

Public Domain

Charles Darwin’s original edition of “On the Origin of Species” didn’t include citations, a preface, or other acknowledgement that others’ thoughts may have laid the groundwork for his famed 1859 revolutionary book on his evolutionary ideas.

Then the letters started, as William “Ned” Friedman, Arnold Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, described recently.

Within a month, a stream of correspondence began, pointing out that others had had thoughts on the topic well before 1859. They came from famed scientists and thinkers of the time such as Joseph Hooker, Charles Naudin, Baden Powell, Robert Chambers, and Herbert Spencer. He even got a letter a year before publication, from Alfred Russel Wallace, containing a manuscript that so mirrored Darwin’s ideas that it spurred his friends into action to establish the primacy of Darwin’s theories and jolted Darwin himself into a writing frenzy from which the landmark book emerged.

For the second edition of “On the Origin of Species,” Friedman said, Darwin added a preface recognizing the many authors — 37 from the U.S. and Europe — whose writings on evolution preceded his own, but even that didn’t prove enough. As Darwin’s fame grew, so did the number of those who claimed to have thought of evolution — or at least about it — years before.

Indeed, said Friedman, who has studied the history of evolutionary thought, Darwin’s ideas formed amid a rich stew of thinking in the decades before publication of “On the Origin of Species” about the source of nature’s breathtaking variety. Common among many authors, Friedman said, was an understanding of plant and animal breeding through which humans improved production, enhanced beauty, or locked in some desirable trait. It was a short intellectual jump to how a similar process might occur in nature, driven not by humans, but by shifting natural conditions.

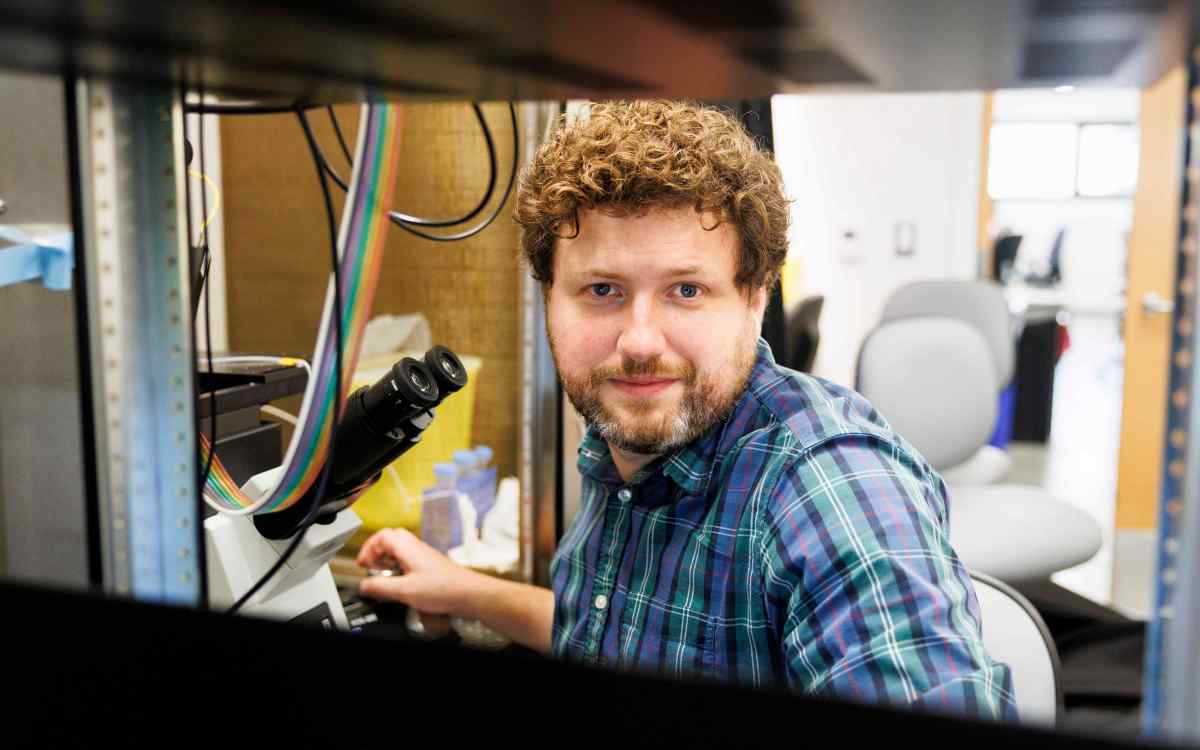

As Darwin’s fame grew, so did the number of those who claimed to have thought of evolution — or at least about it — years before, explained Arnold Arboretum Director William “Ned” Friedman.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

“Evolution was all over the place. Darwin grew up in a world that talked about evolution,” said Friedman, director of Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum. Friedman spoke Tuesday evening before a standing room only crowd at Harvard’s Geological Lecture Hall. The talk, “Who Discovered Evolution?”, was part of the Harvard Museums of Science and Culture’s “Evolution Matters” lecture series, supported by Herman and Joan Suit.

The intellectual world in which Darwin steeped was close to home as well. Among the early authors writing about evolution was Erasmus Darwin, Charles’ grandfather, whose 1794 book “Zoonomia” contained some early ideas about evolution.

Friedman’s own investigation has revealed 70 different authors writing on the topic, stretching all the way back to the philosopher Lucretius in 50 B.C. Even that list, Friedman said, is almost certainly incomplete. The morning before he spoke, Friedman received a suggestion he investigate four Italian authors, and he acknowledged that his own investigation focused heavily on Darwin’s European and American context and doesn’t include possible early thinkers in other parts of the globe.

Despite the ongoing evolutionary conversation in Darwin’s time, Friedman believes that Darwin’s thinking was original, though he did express skepticism at Darwin’s claims of ignorance of own his grandfather’s ideas. Darwin’s writings — not to mention the years spent traveling the world on the Beagle — establish that he was thinking about evolution long before “On the Origin of Species” was released. In fact, Friedman said, one reason he hadn’t published his ideas earlier was because he was at work on a much larger volume dedicated to the concept — which he set aside to hurriedly write “an abstract” that became “On the Origin of Species.” That turned out to be a happy occurrence, Friedman said.

“He’s got this gargantuan manuscript, a thousand citations, details. I read it,” Friedman said of the larger book, published after Darwin’s death. “It is unreadable.”

While those early authors almost certainly provided Darwin food for thought, Friedman said Darwin deserves credit not only for his own ideas but also for synthesizing them into a robust scientific framework and recognizing that framework’s importance to our understanding of life on Earth. Also underappreciated, Friedman said, is the importance of Darwin’s ability to put those ideas in readable form and his tireless work spreading and defending them.

“I have a lot of ideas. … It may even be that some of them are fantastic,” Friedman said. “But if I never put pen to paper, they’re worthless. That’s just a fact. The ideas that matter are the ideas that are put out and tested in the world.”

Even Wallace, whose thoughts were so close to Darwin’s own, later thanked Darwin for his work in service to evolutionary theory, saying “On the Origin of Species” made an argument that convinced the world as Wallace never could have, and revolutionized the study of natural history along the way.

“So, who discovered evolution?” Friedman said. “Charles Darwin — in a sense — but he was the world’s 70th evolutionist.”