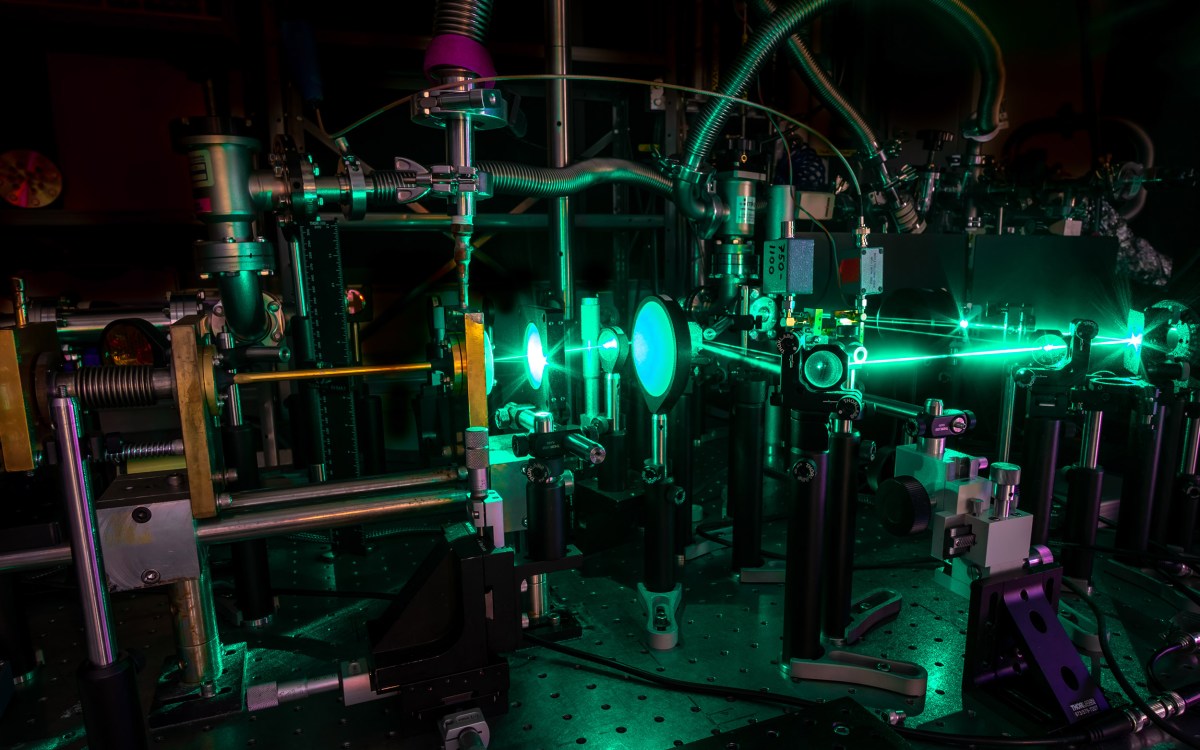

Rox Anderson (left) and Lilit Garibyan are leading an ongoing project that provides laser surgery to children in Armenia affected by port-wine stain and hemangioma.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Helping hands bring laser light to Armenia

MGH Wellman Center physicians bring treatment for port-wine stain, hemangioma, scars to Armenia

When Lilit Garibyan left her native Armenia in 1991, the Eurasian nation was at war with neighboring Azerbaijan, and Garibyan was a 12-year-old who knew she would go back someday, but, she later decided, not before she had something to offer.

Garibyan returned in 2013, bringing medical expertise and high-tech lasers to the capital, Yerevan. On that first trip, she and the two doctors who accompanied her worked long days treating disfiguring skin conditions, including scarring, the bright-red vascular tumor called hemangioma, and the capillary malformation that results in the discoloration known as port-wine stain.

Garibyan, a Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) dermatologist and assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, has since visited annually and worked with U.S. and Armenian partners to secure donated lasers, train local physicians to run them, and establish a nonprofit, Face of Angel, to foster the work.

“It was emotional to go back after being away for 22 years, to see the country you came from. I saw my relatives,” Garibyan said. “I hadn’t gone back because I wanted to go back when I could give something back. I didn’t just want to go say, ‘Hi, I’m Lilit. Nice to see you again.’”

Garibyan, a physician-scientist at MGH’s Wellman Center for Photomedicine, said that the targeted conditions can have serious complications, including blindness when they occur near the eye, cognitive issues if in the brain, or bleeding and functional difficulties in affected body parts, particularly the hand and foot. But, she added, the most common — and often most debilitating — effects are often psychological.

“The psychological impact is huge,” Garibyan said. “Kids don’t want to go outside. They don’t want to interact with others as they feel embarrassed. They’re ostracized because they appear different from others.”

In the U.S., port-wine stains are typically treated with lasers when patients are young, as are hemangiomas when they fail to fade over time, as often occurs. The precision laser treatment, given over the course of several months, can effectively erase them, Garibyan said. In developing and middle-income nations, however, both the sophisticated lasers used to seal off leaky, malformed blood vessels and knowledge of how to run them are scarce. Those barriers to treatment are what Garibyan and a team from the Wellman Center, including the center’s director, Professor of Dermatology R. Rox Anderson — who ran a similar program in Vietnam — seek to clear.

Statistics aren’t available about how widespread the conditions are in Armenia, in part because, without effective treatment, individuals tend to keep to themselves or hide affected skin under clothing, according to Khachanush Hakobyan, executive director of the Armenian American Wellness Center, one of two centers collaborating with the American doctors. Seven years into the program, demand for treatment shows no signs of lessening. The Armenian American Wellness Center — which charges nothing to treat children — is actively reaching out, advertising on Facebook, and appearing on local television programs, and the patients keep coming.

Hovik Stepanyan, an Armenian physician whom the MGH team trained to use the lasers, said the center sees about 20 new patients a month, and the yearly totals have increased to about 220 today and are still rising.

Stepanyan, who has become a local expert in the laser treatment and is consulted widely in the region, said that what has been helpful to him has been not only the initial training, but also the ongoing collaboration, which allows him to send images and consult with the MGH physicians on tricky cases. He’s also traveled to Boston several times for the Harvard continuing medical education laser conferences.

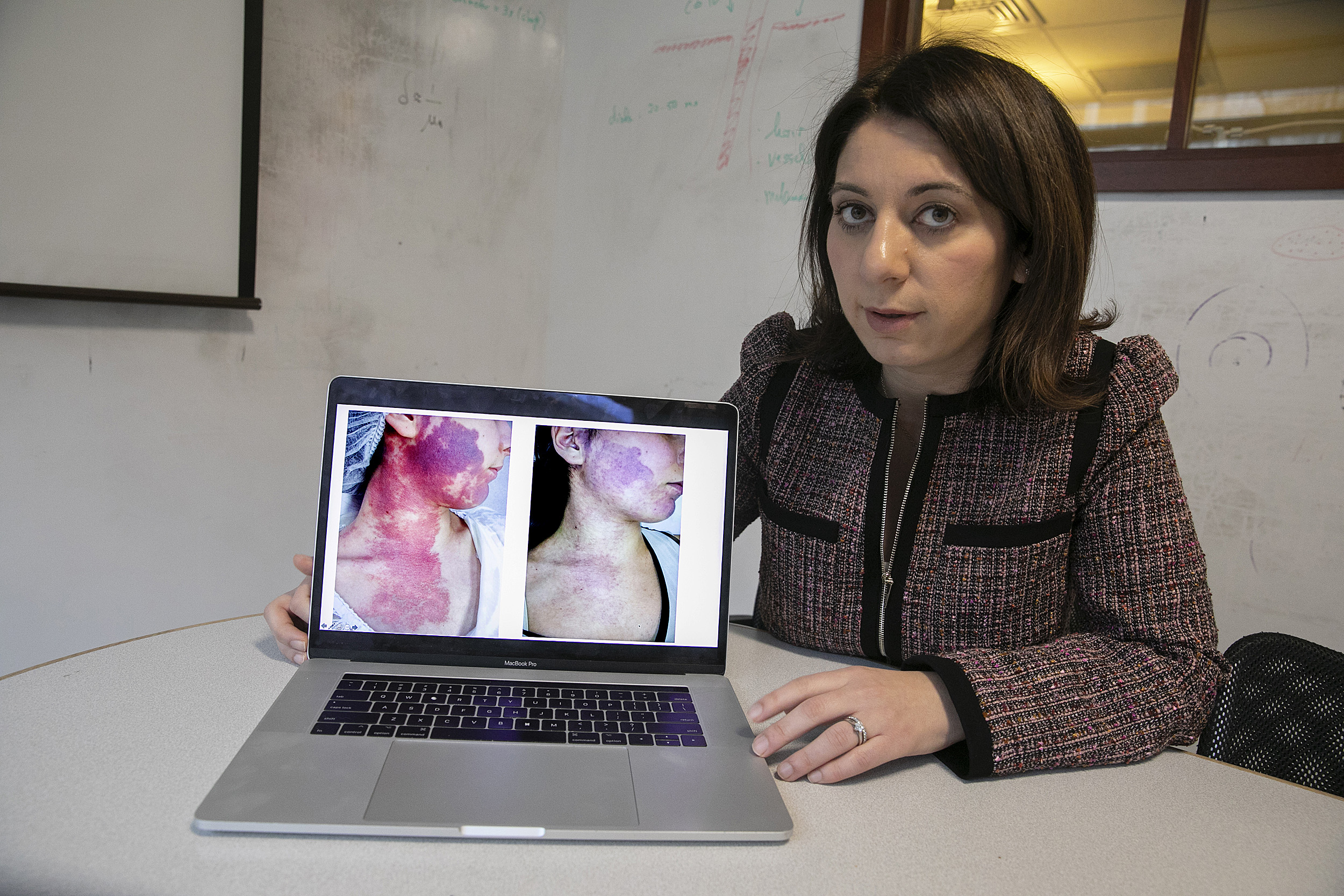

Lilit Garibyan displays before and after photos of laser treatment on a patient with port-wine stain.

Mary Aloyan, 14, from Gyumri, 160 miles from Yerevan, is about 90 percent through the treatment for port-wine stain on her face. She said the laser procedures can be painful, but not intolerably so, and her parents said the results have been worth it.

“As my child was growing, she was feeling unconfident and ashamed. We decided to apply for laser treatment,” said A. Aloyan, Mary’s father. “We haven’t finished treatment yet, but the results are obvious, and we plan to continue the interventions until my daughter will have a port-wine-stain-free face. My child is more confident and does not concentrate on the port-wine stain on her face. We are happy.”

Aloyan said he’d definitely recommend the treatment for others, as it improves the quality of life for patients and their families.

“As a parent, it’s hard when your daughter goes through all of this, but the results are encouraging,” Aloyan said.

Garibyan is no stranger to family sacrifice. Her parents left Armenia for Glendale, Calif., fearing that her younger brother would be pressed into service amid their nation’s widening war with Azerbaijan. They choose Glendale because of its large Armenian community.

Garibyan arrived at Los Angeles International Airport speaking not a word of English, and she still recalls the confusion and dislocation of her first months in America — especially in the classroom — as she wrestled with a new language. Garibyan’s mother thought their stay would be brief, but months became years, laden with cultural and financial challenges. As Garibyan’s English improved, so did her grades. Against the advice of a high school guidance counselor who thought community college was her best bet, Garibyan applied to the University of California, Los Angeles, and was admitted. She studied science and spent a consequential summer at the University of California at San Francisco lab of Donald Ganem, a Harvard Medical School alumnus who urged her to apply to Harvard’s M.D./Ph.D. program.

Garibyan graduated with a doctorate from Harvard’s Biological and Biomedical Sciences program in 2007, and then earned her M.D. from HMS in 2009. After her residency in dermatology, Garibyan encountered a high school friend, Ray Jalian, who was working as a fellow with Anderson at MGH’s Wellman Center. Drawn by the promise of conducting translational research that could have a direct impact on patients’ lives, Garibyan joined the lab. Now she’s conducting studies on an injectable coolant that she and her team invented and developed in the lab. They intend to use this for removing disease-causing fat tissue in the body and for treating pain. This coolant is able to reduce pain by numbing nerves without resorting to the extreme cold typically used in cryotherapy. Garibyan hopes her discovery will reduce or eliminate the need for opioids to treat pain, thus helping fight the deadly epidemic of drug abuse ravaging the nation.

The Armenia program grew out of Anderson’s earlier efforts in Vietnam, where he and colleagues performed laser surgery for the same vascular problems as in the Armenia program. Garibyan met an Armenian plastic surgeon who was visiting Boston University and who’d spent some time at Anderson’s lab. After seeing their work, he urged them to bring their expertise with laser surgery for vascular abnormalities to Armenia.

“Rox said, ‘OK, let’s go,’” Garibyan said. “I was like, ‘What? I have to ask my boss.’ He said, ‘I am your boss.’ So I said, ‘Yes, we should go.’”

“There were people who felt that they couldn’t work or face anybody with this problem. It’s a real social concern. One of them found out I was the one who sent the laser, and she started crying. It was such an easy thing. You do these treatments, and the results are so amazing.”

Christine Avakoff, dermatologist

That first trip, in 2013, coincided with a plastic surgery conference in the capital, and included Garibyan, Anderson, and Jalian. They brought a borrowed laser and focused on treating scars, port-wine stains, and hemangiomas.

“The first day we saw over 70 consultations. There were so many people wanting to be seen for scars and vascular anomalies,” Garibyan said. “We had to use our creativity and imagination. We were only given the dentist’s room to work out of, so we divided the room into three sections: pre-op, treatment, and post-op.”

In addition to consulting with patients and treating those they could, they also taught local physicians to use the lasers and gave lectures at the plastic surgery conference.

“I was really happy because I had now created something where I could meaningfully give back,” Garibyan said. “We decided that we will do this every year, and we could make it into the same program that the Vietnam project had become.”

The program benefited early on from the involvement of California dermatologist Christine Avakoff and her husband, physician John Poochigian, who have traveled regularly to Armenia since 2000. It was Avakoff who introduced Garibyan to the Armenian American Wellness Center, which, along with Arabkir Hospital, has become one of the collaboration’s primary sites in Armenia. Avakoff, who was retiring, donated the first laser to the center — six have been donated so far, with the major donors being the Candela and Quanta laser companies. Garibyan also worked with Avakoff and Poochigian to establish Face of Angel to support the work there.

Avakoff and Poochigian are of Armenian ancestry and were struck on their travels by the number of people with visible vascular abnormalities that are relatively easily treated in the U.S. Avakoff said she recalled one boy who had a port-wine stain on his feet, which bled when he walked. Others had gone blind because the condition had been untreated, while still others had suffered disfiguring surgeries using 1970s-era lasers, Avakoff said.

“There were people who felt that they couldn’t work or face anybody with this problem. It’s a real social concern,” Avakoff said. “One of them found out I was the one who sent the laser, and she started crying. It was such an easy thing. You do these treatments, and the results are so amazing.”

While Garibyan is planning a trip with several colleagues to Yerevan this spring, word is spreading about the program and its predecessor in Vietnam. Avakoff said the program has begun to draw patients from neighboring countries, including Russia. A lawmaker in Montenegro heard about the program through one of the participating physicians and asked whether they’d bring it there.

“We might go there for a few days on the way back from Armenia, do an assessment, and see what they need,” Garibyan said.