Photo courtesy of Dulac Lab

Scaled-down labs felt ‘this special responsibility’

Harvard scientists put research on hold for safety, saw chance to help hospitals with precious gear

This is part of our Coronavirus Update series in which Harvard specialists in epidemiology, infectious disease, economics, politics, and other disciplines offer insights into what the latest developments in the COVID-19 outbreak may bring.

Sarah Fortune leads a lab of about 20 scientists who study tuberculosis. The lab at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health is in a biosafety level 3 containment facility, so researchers must wear N95 personal respirator masks and full-body Tyvek protection suits to experiment on specimens of the disease that in 2018 killed 1.5 million worldwide.

The researchers investigate drug resistance and host response, which is important in preclinical vaccine development. But last week, as the numbers of COVID-19 cases in Massachusetts and the U.S. continued to rise, Fortune had to make a gut-wrenching decision.

Her lab came to a complete stop.

Scientists saved what data they could and destroyed cultures and other materials they couldn’t, but they didn’t stop there. They donated their masks, suits, and respirators to local health care clinics to use as coronavirus cases continue to escalate.

“We have this special responsibility to share our personal protective equipment with health care workers,” said Fortune, the John LaPorte Given Professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases at the Chan School who is also director of the TB Research Program at the Ragon Institute of MGH, Harvard, and MIT. “We all feel like if we — especially us who understand so clearly what this could be — don’t really fully make hard sacrifices, then how could we ask anybody else in our community to do that?”

Decisions like this are happening all across Harvard as scientists have rapidly scaled down the work in their laboratories to only essential functions as part of a massive effort to de-densify the University and lower the risk of infection through social distancing. In some cases, they’ve also had to figure out how to keep research subjects alive and sensitive equipment functioning. At the same time, other Harvard labs are racing to learn the secrets of coronavirus in the search for a vaccine.

Labs have closed in the Faculty of Arts and Science’s Division of Science, the Harvard John E. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), Harvard Medical School, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard Dental School, and affiliated hospitals. The closure’s affect a wide range of scientific studies, from plants and rocks to Alzheimer’s and cancer.

“We all feel like if we — especially us who understand so clearly what this could be — don’t really fully make hard sacrifices, then how could we ask anybody else in our community to do that?”

Sarah Fortune, John LaPorte Given Professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases

The ramp-down went into wide effect on March 18.

The first announcement of the scale-down came in a March 12 email co-written by FAS Dean Claudine Gay, SEAS Dean Francis J. Doyle III, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Dean Emma Dench, Dean of Science Christopher W. Stubbs, Dean of Social Science Lawrence D. Bobo, and Dean of Arts and Humanities Robin E. Kelsey.

The next day the deans of the Medical School, Dental School, and the School of Public Health jointly announced they, too, would be entering a period of “low productivity.” On Saturday, the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard followed suit, as did the Wyss Institute.

The deans asked principal investigators to identify key individuals and essential tasks that must be completed during the ramp-down to avoid significant financial and data loss.

“The policy that we put in place asks the research community to limit their time on campus to sustaining research organisms, keeping irreplaceable samples, and making sure that high-value apparatus doesn’t get damaged,” Stubbs said. “It’s essentially putting our research activities into suspended animation.”

Stubbs said the impact on both cost and careers was carefully considered before the decision was made, but it was important to act decisively to help flatten the curve of coronavirus infections.

“It’s essential that we keep, to the maximum extent possible, the number of people who turn up at hospitals within the capacity of the healthcare system,” he said. “I don’t mean to be alarmist here, but we’re trying to reduce the number of people who are going to die.”

Normally, scientific research never stops. But by the end of business on March 18, many projects at Harvard effectively went dark. Leading up to that, many labs worked to make sure machines such as cryogenic freezers and superconducting magnets would be properly maintained by essential staff, and that the model organisms they work with — fruit flies, worms, and zebrafish — would be well cared for as most research scientists observe social distancing guidelines.

Roger Fu, assistant professor of earth and planetary sciences at FAS, said no one from his paleomagnetics lab will be going into the physically lab space for the duration of the scale-down. Instead, his team of eight postdoctoral fellows, graduate students, and undergrads will do remote data analysis with the computers and equipment they took home. The team studies the magnetic properties of rocks to understand planet formation and the early Earth.

Roger Fu’s team uses a magnetometer (right) for their research.

Photo by Roger Fu

Harvard building facilities will check on key hardware that the researchers left in standby mode, including the magnetometer, which runs on a cryogenic coolant system. Fu said that although “there’s nothing that would die if we’re not in the lab every day,” the magnetometer could be damaged if the cooling system malfunctioned.

In the Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases at the Chan School, however, the malaria group must keep alive malaria parasites grown in red blood cells and the mosquito colonies that transmit these parasites. Two or three essential personnel will go in to care for the mosquitoes, which are housed at Catteruccia Lab.

Among other research, the work at the lab helps develop new interventions, including vaccines and drugs, said Dyann F. Wirth, the Richard Pearson Strong Professor of Infectious Diseases. Every year, there are more than 200 million new cases of malaria, and more than 400,000 people die from the disease, Wirth said.

“Mosquitoes can’t be frozen, so they must be maintained in their reproductive cycle,” she said. “They need to be fed and transferred. There’s a whole mosquito-breeding protocol, so that will need to be maintained. It’s a very specialized set of skills.”

Neuroscientist Catherine Dulac faces similar issues at her lab. The Higgins Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology and the Lee and Ezpeleta Professor of Arts and Sciences has mice that her lab uses to study the brain control of social behavior.

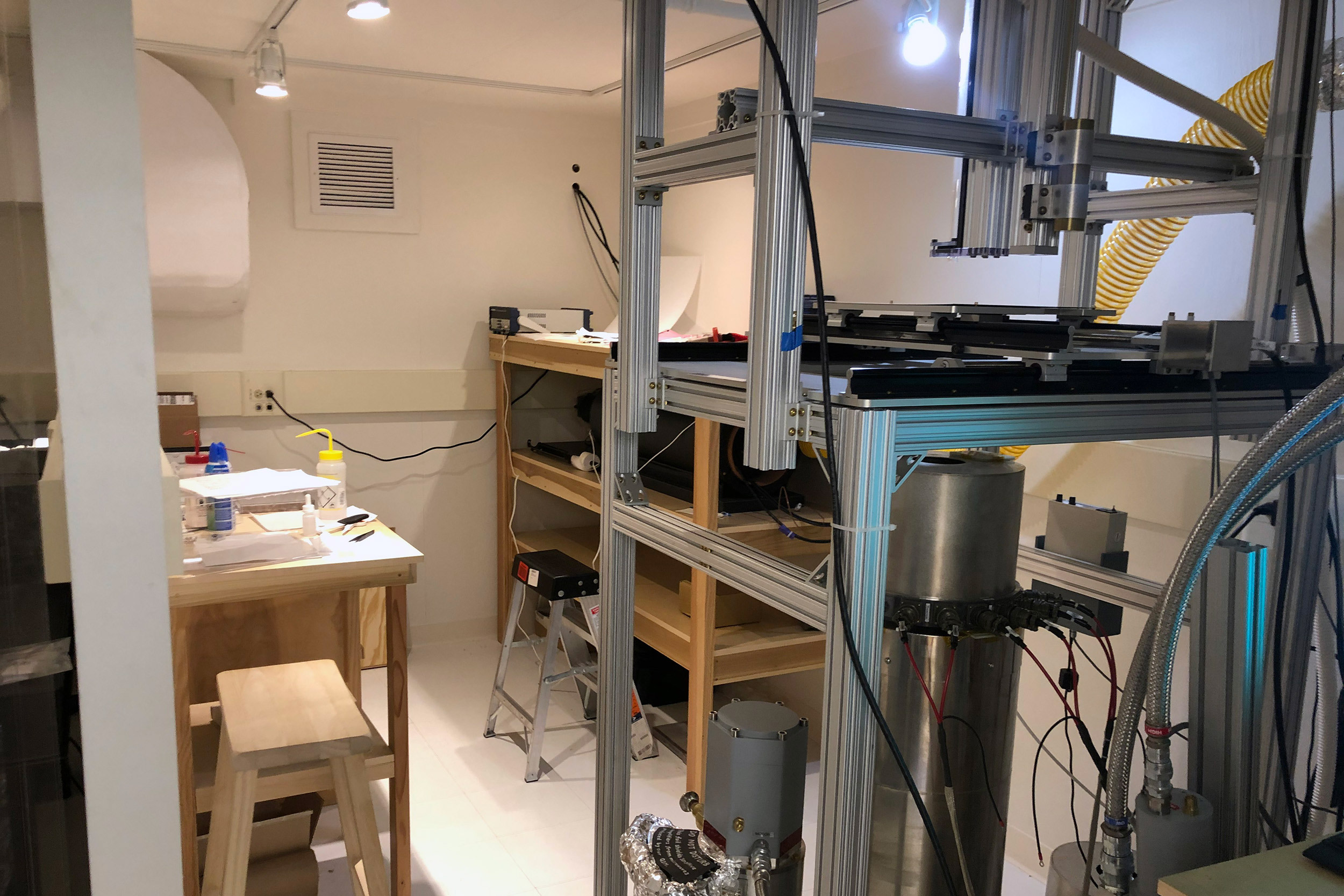

Liquid nitrogen tanks are being stored in Catherine Dulac’s lab.

Photo courtesy of Dulac Lab

“For us, our most important resources are the mouse lines and our frozen stock of cell lines in liquid nitrogen,” said Dulac, who is also a Howard Hughes investigator. “We have established a very minimal crew of people who are each going to come once or twice a week and have a long list of things to do, checking and taking care of the mice for multiple labs to minimize the number of people who need to get in.”

Along with tending to the mice, lab members will also monitor and refill the tanks of carbon dioxide that sustain long-term cell cultures that cannot be frozen, and tanks of liquid nitrogen that keep large stocks of frozen cell lines properly cooled.

Many Harvard science labs can rely on teams devoted specifically to animal care.

Labs are also donating key materials and equipment to front-line health care workers. Fortune’s lab along with other labs at the Chan School donated 15 cases of N95 masks, 500 protection suits, and close to 4,000 gloves to Harvard University Health Services and the East Boston Neighborhood Health Center.

Matthew Volpe, a fourth-year graduate student in the FAS Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, said the Balskus Lab donated its RNA extraction kits — which are essential to coronavirus testing — to Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Volpe, who studies gut microbes including E. coli, said other research labs at FAS have done the same. On Wednesday, Volpe paid his last visit to the lab for the immediate future to package human cancer cell lines in the biosafety cabinet and freeze them for long-term storage.

At the Balskus Lab, human cancer cell lines are being frozen in a biosafety cabinet for the foreseeable future.

Photo by Matthew Volpe

The researchers’ efforts are proof of Harvard’s commitment to putting public health needs ahead of their own work during a time of crisis.

“Our researchers are cooperating fully,” said SEAS’s Doyle, especially “since the consequences involved [could] have life-and-death ramifications in the community.”

Still, many researchers are concerned about long-term effects on their work as the pandemic stretches out. The University recommended researchers devote their time to writing grant proposals, reviewing articles and papers, writing thesis chapters, data analysis, planning future work. Many plan on doing just that.

Frank Keutsch, the Stonington Professor of Engineering and Atmospheric Science and a professor of chemistry and chemical biology, wonders what will happen if or when that work runs out.

“As this starts getting much longer, and going into summer, at some point, we’ll have to really rethink, in some sense, the research we’re doing, and what we’re doing [day to day],” he said. “A lot of my research is based on experiments. At some point, the external data that you have sitting in your pocket that needs work is going to run out, and then we’ll have to transition.”

Keutsch’s lab at SEAS studies atmosphere and plant interactions to see how humans are changing the chemical processes in the atmosphere. During the scale-down, the lab safety officer will be going into the lab to monitor the health of the plants.

A few researchers, like some at the Harvard Forest, are more fortunate when it comes to their experiments. A small number of researchers there still will be able to monitor plants in the field to sustain long-term data records for their experiments. They will have to travel to the forest alone and maintain the recommended social distance from others while there, said Jonathan Thompson, a senior investigator for the forest’s long-term ecological research program. There are also a number of automated sensors that will continue to collect data on trees.

Within the Harvard Forest, a sign explains the heated soil experiment to research microbes, an experiment that has been ongoing for more than 20 years in Petersham, Mass.

Kai-Jae Wang/Harvard file photo

Researchers will be able to access the data from computers and other equipment they took home, Thompson added. Maintenance on the forest’s research towers will be allowed during the scale-down, but all onsite labs are closed.

One concern among laboratory scientists getting accustomed to working remotely is the line between social distancing and social isolation. To guard againt this, Keutsch said he’s introduced a number of social forums for his lab and is starting a weekly kaffeeklatsch, “a German word for when you have coffee and talk about stuff,” he said. “Purely social.”

In her now-virtual laboratory, Monica Colaiácovo, professor of genetics in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School, said she is setting up similar one-on-one meetings with everyone in her lab on the Longwood Campus, where researchers study the cell-division process meiosis. Last week, they worked furiously to freeze many of the microscopic worms called C. elegans that were close to being ready for analysis. During the scale-down, a member of her lab will go in once a week to refill the liquid nitrogen that cools the cryofreezer where the worms are stored. Colaiácovo estimates that when they are allowed to restart work they can be fully operational in seven to 10 days.

Another researcher at HMS, where all research has stopped except work related to coronavirus, is Michael Crickmore. He is assistant professor of neurology at the School and a research associate in the Kirby Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, where his lab studies fruit flies to understand motivational states.

“It’s really sad,” Crickmore said. “It’s sad for me as a relatively new [principal investigator] living out a dream to have a beautiful lab at a place like this and being able to chase big discoveries every day — also for people who are in my lab and are just finding out what it’s like to make discoveries and get addicted to it. To have to put that aside is super sad for us just like it is for everybody else.”

But, he said, they realize what’s at stake, and are ready to play their part.