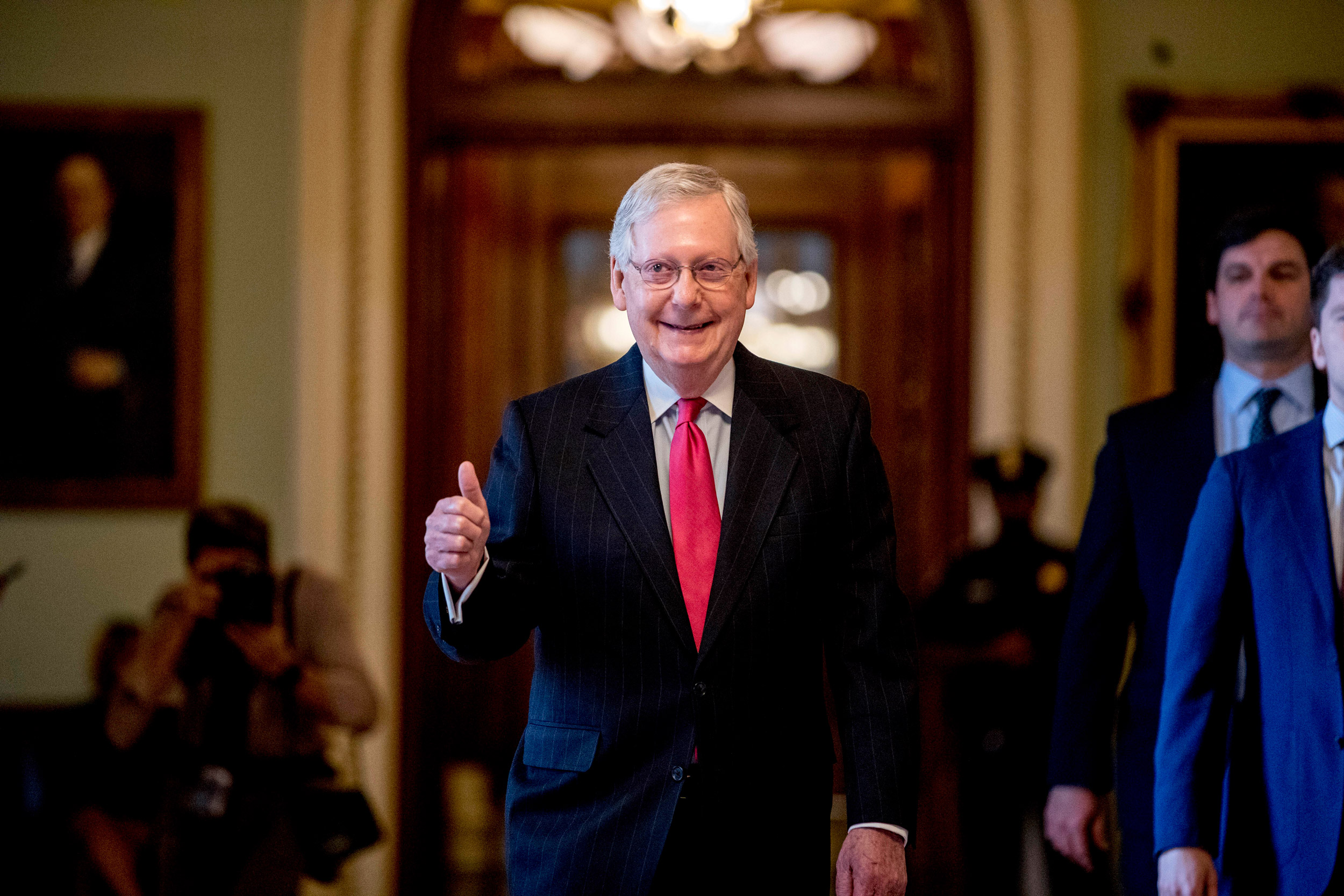

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell gives a thumbs up as he leaves the Senate chamber on Capitol Hill in Washington on Wednesday where a deal has been reached on a coronavirus bill.

AP Photo/Andrew Harnik

Economists cheered by relief package but see long, tough slog ahead

Karen Dynan and Kenneth Rogoff say Fed and Congress are moving in the right direction

This is part of our Coronavirus Update series in which Harvard specialists in epidemiology, infectious disease, economics, politics, and other disciplines offer insights into what the latest developments in the COVID-19 outbreak may bring.

The Senate late Wednesday passed a wide-ranging, record $2 trillion relief package targeting individuals, businesses, and city and state governments left reeling by the coronavirus pandemic. Harvard Kennedy School Professor Karen Dynan, Ph.D. ’92, served as chief economist and assistant secretary for economic policy at the U.S. Department of the Treasury from 2014 to 2017. She’s currently teaching an economics course called “The Financial Crisis and the Great Recession.” Kenneth S. Rogoff, Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy and professor of economics in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, is a former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund and an author of an influential history of global financial crises, “This Time Is Different” (2009), with Kennedy School economist Carmen M. Reinhart. Dynan and Rogoff spoke about recent moves by the Fed to calm jitters on Wall Street, the relief package, how deep the damage may go, and how soon the economy might bounce back.

Q&A

Karen Dynan and Kenneth S. Rogoff

GAZETTE: What do you think about the stimulus package? Given the scope of the pandemic’s impact, what does it accomplish and where does it fall short?

DYNAN: I think the stimulus deal that the Senate has agreed on has a lot of positive features. It has money to send to individuals to help them get through what’s likely to be a very tough period for many of them. Many hard-hit families will also get some relief from the additional unemployment insurance benefits provided by the bill — an extra $600 a week could be a big deal for them. The package also has substantial funding for loans to small businesses to help them stay afloat. Importantly, these loans can be forgiven if they are used to retain and keep paying their workers. It has money that will help the Fed do more lending, some funds for direct loans to larger businesses, money for the health care system, and funds to help states and localities deal with the crisis. The latter is really important, as state and local finances are going to be hit really hard, and it’s especially critical that they don’t pare back social programs and essential services right now.

Depending on how the crisis unfolds, we may need to spend more in all these areas but, all in all, I think the package is a really good start. We now need to turn our focus toward how to get these measures implemented well. We have never tried to do some of these things before — like lending to small businesses on this scale — and it’s super important that the money goes out quickly and effectively.

ROGOFF: I think it’s a tremendous first step. I don’t think this is anywhere near the end. We’ve pushed the pause button on the U.S. economy. Estimates of how much it’s actually going to go down in the second quarter are all over the map because, really, how do you estimate it? Even people who form GDP statistics aren’t able to get a great estimate because it’s so far off the norm. We’re in a war, and I think this has to be viewed in this perspective, where you pull out all the stops.

There are so many people in our economy who don’t fit into regular jobs. Some countries, like Denmark, which have a much smaller informal economy and a smaller gig economy, have concentrated on paying lost wages directly. The U.K. has said that it’s going to do the same thing. We have so many people [for whom] that’s not going to work so easily, and so this idea of capturing everyone in the economy, making [direct] transfers, is definitely a good path, as is focusing on small businesses, which have been extraordinarily hard-hit. So this was a very, very good first step.

The loans to the corporations: If they don’t do it, they have to force the Federal Reserve into doing it, and the U.S. Treasury owns the Federal Reserve. They’re just doing it in a more transparent way. You can’t let all our airlines go bankrupt. There may be some progressives who would feel good about that. But it’s pretty destructive. Carbon tax, yes. Letting all our airlines go bankrupt, no. I don’t think that’s something that we want to do. Large corporations employ a lot of people, and many of them are being hit just like the small businesses are for problems they didn’t create. And if they’re not being directly hit, maybe they’re still functioning. But the ones that are directly impinged, in the travel industry in particular, they’re all going to go bankrupt, and it’s going to be a mess, and we want to try to forestall that.

[Assigning an inspector general to oversee the fund disbursement:] That was a fine idea to give more structure, especially given the lack of trust in the administration. That was a constructive change that both sides should have wanted. I think the Democrats made a lot of constructive suggestions. I’m not in the politics of this, but this is a real war, not a political war. A lot of the debt battles in recent years have really been political. They’re called wars, but they’re not. This is a war, and it’s good to see some consensus.

GAZETTE: Given its size and scope, is this likely all the relief we’ll see from Congress?

DYNAN: If this does not appear to be offering enough support to the economy, I think Congress will step in and take additional steps.

ROGOFF: Unless we get lucky on having an extremely effective antiviral drug or something very quickly, it’s not going to be the end. The health sector is the front of this war. We’re supporting the economy, but if you think about what needs to be done in the first instance, it’s in the health sector at the national level. First and foremost, there should be absolute, widespread free testing not just for people who are acutely ill, but also for people who might have been infected and recovered. That would be so beneficial, if we spent tens of billions of dollars and accomplished that. It’s a fantastic investment. So yes, we need respirators; we need masks; we need personnel to deal with the acutely ill. But in order to know how to deal with this and how to manage the economy, you need to know who’s infected, who’s recovered, and who’s not infected. I would frankly like to see more of a wartime-type mobilization on that front than we’ve seen so far. But in terms of the rest, there will be other costs before lost tax revenues. I’m sure there will be many areas missed that they’ll have to fill in. But if we come out of this just having lost an extra $5 trillion and the economy recovers, that’s going to be a great outcome. The whole point of saving for a rainy day is precisely to be able to borrow with abandon in a situation like this — the worst thing to hit us in 100 years or more.

The biggest question here is: How long will this last? Because if it lasts until we get a vaccine, the amount of wealth destruction is going to be staggering and unavoidable …,” said Professor of Economics Ken Rogoff.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

GAZETTE: The Federal Reserve has taken a host of extraordinary steps in the last 10 days to stabilize the markets and prevent the economy from sliding into a depression. What’s your assessment of these measures?

DYNAN: Financial markets have been in tumult, in part because of a desperate need for cash, as businesses anticipate lower revenues but also have bills they need to keep paying. So businesses, and also the banks that might lend to businesses, are dumping large amounts of stocks and bonds into the market, and that’s causing a lot of volatility. What the Fed is doing is saying, “Hey folks, we’re here to buy those securities, or lend you money using those securities as collateral. So you don’t need to scramble like this.” This is basically the same playbook that the Fed and other central banks used during the 2008 financial crisis, and it did eventually calm markets. I think we’ll still continue to see some big market swings as unsettling news about the virus continues to come in, and also the Fed may need to eventually broaden its efforts. I also think the Fed’s efforts will ultimately work in stabilizing the financial system because all the various steps are setting the Fed up to act as what’s called “the lender of last resort,” providing liquidity when no one else will. And, the various pieces they’ve put in place have been about broadening the group that will be able to take advantage of those programs.

ROGOFF: The Fed made a huge difference. The financial sector was melting down and going into wholesale financial panic. Everyone was selling everything to go into Treasury bills. An example of something Fed officials did that was creative and a little bit daring was they backed money market funds after swearing on a Bible that they wouldn’t back them in the Dodd-Frank bill. And of course, there was a massive run on money funds, crushing the debt market and leading to a chain reaction. I think Fed [officials] did a number of things pushing to the limits what they thought they could legally do, and they’re probably going to need to be given authority to do more. There may be debate about it in Congress when the system’s melting down again. The only reason it’s not at the moment is that everyone believes the Fed will be able to do more. But we were in full-scale, global panic, and the Fed’s actions and the other central banks’ actions, have at least for the moment stopped that. There’s much more to come. The biggest question here is: How long will this last? Because if it lasts until we get a vaccine, the amount of wealth destruction is going to be staggering and unavoidable, and it’s going to take a lot more than we’ve seen so far by the government.

GAZETTE: What else is left to be done if these measures do not have their intended effect?

DYNAN: They can expand access to these kinds of programs. For example, they’ve announced, but not put in place, a program that will lend to small businesses. We know that small businesses will need a lot of support given what’s happening to their revenues. That’s an additional measure that should help.

ROGOFF: The central bank, primarily, is in charge of monetary policy — that’s setting the interest rate, the liquidity in the economy. Another task is to be a lender of last resort when a bank is failing. Here, and also in 2008, the Fed has performed a third task as a market maker of last resort, which is that if no one wanted to buy or trade in some assets, they’ve been able to step in. I do think at this point it would be helpful to expand the Fed’s authority to be able to buy corporate debt if the worst comes — Fed leaders are asking for that. But the main role is fiscal policy. There are limits to the Fed’s fiscal policy: If the Fed were to take a $500 billion loss on its portfolio by extending into extremely risky debt, essentially the Treasury has to absorb this. And these bigger decisions, even though in heat of battle the Fed’s independence helps it get out in front, at the end of the day, the Treasury, the Senate and the House, and the president have to sign off on things. So, as much as we fear the discord in our political system, we have to rely on it to resolve these problems.

This crisis once again proves how absolutely essential central bank independence is. President Trump has certainly made comments undermining it, and the progressives have argued for reabsorbing the Fed back into the government and having the government running the Fed much more directly than it does. Had that happened, the Fed would have been paralyzed, and it would not have been able to act like this. It would not have been able to move in. It’s fortunate that that hasn’t happened, and I hope this proves as a reminder to people that in crisis situations, we need technocrats. We need to have an independent central bank.

“It depends partly on how the spread of the virus evolves. But it also depends, really importantly, on the policies we’re putting in place and whether they’re well targeted … With the right policies, we could see a really strong rebound,” said Harvard Kennedy School Professor Karen Dynan.

Courtesy of Karen Dynan

GAZETTE: How bad could things get?

ROGOFF: It depends on how we’re able to restart the economy. I’ve worked with colleagues in the Harvard Chan School of Public Health and at Harvard Medical School over the years … If there can be widespread testing, all of a sudden a lot of options are on the table to restart the economy. The people who are immune, who may prove to be a great many, can immediately re-enter the workforce; the people who are tested [but] currently have an active infection can be isolated. Instead, we’re just blind, shutting down the entire economy because we failed to prepare for having testing, and we’re having to use this very crude instrument. It’s very possible that the situation will improve dramatically, and it will be possible to restart the economy and start to resume much more normally sometime later this year. We have no idea what’s going on. We don’t 100 percent know that we’ll get a vaccine in 12 to 18 months. That’s hopeful, but it’s not certain. So trying to guess where the real economy is going to go is very tough. We’ve gotten hit by a very bad, real shock.

My colleague Carmen Reinhart and I looked at 800 years of financial crises, and there are many where there was a real shock, a catastrophe, a lost war, a commodity price shock. There were many times when something real hit the economy and was a major cause of why the financial crisis was so bad. There are others where the financial crisis was an accident waiting to happen, and it just took something to catalyze it. This is clearly a case where we’ve been hit by an extraordinarily tough shock that hit the whole world. But it’s going to turn into at least some form of financial crisis, at least in emerging markets, at least in some of the more vulnerable countries like the periphery countries of Europe.

So in places in the world it’s going to last a while, enough so that it reverberates on us. This is what our book says: Once it morphs into a financial crisis or even widespread pockets of financial crisis, it’s much harder to get a very fast recovery. And on top of that, here the real shock is such that we’re shutting down businesses that may struggle to reopen. Some of them may close their doors and reopen quickly. But if it lasts a while you lose employees; you lose suppliers, etc. It may not be so easy. The big question is: How fast can we restart the economy? Even with the government quickly subsidizing a lot of the losses, which is great, it could take quite a while. Having everything roaring back again by the end quarter of this year, like might happen after a normal, natural catastrophe, would be an extraordinarily good outcome. Not impossible, but a long shot at this moment.

GAZETTE: In January, the economic outlook for 2020 was quite positive, although some thought a recession may be on the horizon. Once we’re beyond the crisis point and public health restrictions are lifted, what will be the decisive factors in how quickly we rebound?

DYNAN: One scenario people are talking about now is a sharp rebound of the economy that occurs in the months after life begins to return to normal. But a second scenario is that the economy struggles to get back on its feet, such that the recovery extends into next year or beyond that. So we don’t know which scenario is going to be the one we realize. But a key determinant of what occurs is whether we can avoid permanent or semipermanent damage to the economy in this current period of weakness. So that’s precisely why we don’t want massive job losses or widespread business failures. It’s really hard to get back on your feet after that kind of thing. So we really don’t want to see that. It depends partly on how the spread of the virus evolves. But it also depends, really importantly, on the policies we’re putting in place and whether they’re well targeted, whether they offer enough support in terms of dollars, and whether we can get the support out there quickly to the economy. With the right policies, we could see a really strong rebound.

ROGOFF: It seems, [doctors I talk to] say, awfully likely although not certain that if you’ve had it you’ll be immune, and even if it morphs a bit, you’ll be resistant. So you could have this immune army come back into the workforce who’ve had it at some point. And not just in this country, but people around the world. There will be some developing economies where everyone gets it because they don’t have the wealth to stop everything and feed everyone. If you can identify everyone who’s actively sick and monitor that, and who’s vulnerable, there’s certainly the possibility of [the economy] coming back to something more normal a lot faster. That’s the more optimistic spin. And of course, once there’s a vaccine, that’s better. When you have information, there are a lot of options. When you’re blind, you’re very limited. The biggest tragedy in our response that’s just absolutely unforgiveable is that we were so ill-prepared with the testing and we didn’t anticipate that. You can talk about the respirators; you can talk about the other things; but the countries that have been successful in battling this have been able to monitor; and we haven’t. And this is costing us dearly. I don’t know what’s coming next. But I certainly agree with Carmen that it’s hard to see a V-shaped recovery here, and the depth of the recession could be really quite epic.

Interviews have been edited for clarity and condensed for brevity.