“Race at Uji River,” Soga Shōhaku, c. 1764; “Cranes,” Suzuki Kiitsu, c. 1820–25; “Early Evening at a Yoshiwara Inn, Hishikawa Moronobu,” late 17th century.

© Robert Feinberg, President and Fellows of Harvard College

A peek at a critical time for Japan through its art

Feinberg Collection highlights the rich variety and diversity of the Edo era

An ethereal beauty runs through the Harvard Art Museums’ new exhibit of Japanese paintings drawn from one of the largest and most significant gifts of art ever promised to the University. The more than 120 works that occupy all four of the museums’ third-floor temporary exhibition galleries have been carefully curated from the Feinberg Collection, a trove of more than 300 decorative scrolls, folding screens, fans, woodblock-printed books, sliding doors, and other works. The collection assembled by Robert ’61 and Betsy Feinberg highlights the range and richness of early modern Japanese painting during the Edo period, 1615‒1868.

“They have collected so carefully and with such dedication over the years that they have formed a comprehensive collection. It really allows us to look at the whole gamut of Edo painting, which is incredibly diverse,” said Rachel Saunders, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Curator of Asian Art at the museums, one of the curators of the new show. “It’s a comprehensive history of Japanese art through objects.”

The Feinbergs’ love affair with Japanese works began almost 50 years ago on a trip to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, where the young couple purchased a poster for $2. “Our imagination was captured by its image of a painted 17th-century Nanban screen — a robust, naïve view of a Portuguese sailing ship moored in Nagasaki harbor, manned by strange-looking men with prominent noses and curly moustaches, dressed in outlandish pantaloons and flamboyant hats,” they told the arts magazine Orientations earlier this year. “Edo Japan had never seen anything like them, and neither had we!”

“A Portuguese Trading Ship Arrives in Japan” (detail), unidentified artist, 17th century.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

Visitors to the exhibit will encounter a pair of large, multipaneled screens with almost identical imagery. Nanban art reflects the Japanese response to contact with Europeans, primarily from Portugal and Spain. The screens in Harvard’s show are striking in their detail and composition, said Saunders, and in what they reveal about how the Japanese viewed these outsiders.

“There’s a real sense of the West being exoticized,” she said.

That greater engagement with the wider world was a hallmark of the shogunate, or military dictatorship, that ruled Japan during the Edo period. The era’s peace and prosperity led to a greater openness and ushered in significant social, political, and cultural change, including a vibrant urban culture in which merchants and craftsmen were eager to acquire the visual and material comforts traditionally reserved for the wealthy elite.

“Horse Racing at Kamo Shrine,” unknown artist, early to mid-17th century.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

The Feinberg Collection’s depth of material reflects those trends and shines a light on the varied schools, or lineages, of painting during the period — distinct classifications that embraced different media, subject matter, and even notions of who could be considered an artist. Among the many ideas reflected in the different schools are the embrace of regional landscapes, the foregrounding of human subjects and scenes of everyday life, the influence of Western-style painting, the emulation — and rejection — of classical motifs, and the rise of amateur scholar-painters or literati who employed pared-down materials. Taken together they help illustrate the visual complexity of Japan’s evolving pictorial culture, a key goal of the show, said its curators.

“This exhibit is an opportunity to showcase an artistic tradition that can be likened to early modern European painting as a whole in terms of the breadth of artistry it features,” said Yukio Lippit, Jeffrey T. Chambers and Andrea Okamura Professor of History of Art and Architecture, who co-curated the exhibit. “There are so many schools, so many disparate visual modes, so many lineages of artists active in early modern Japan over 250 years.”

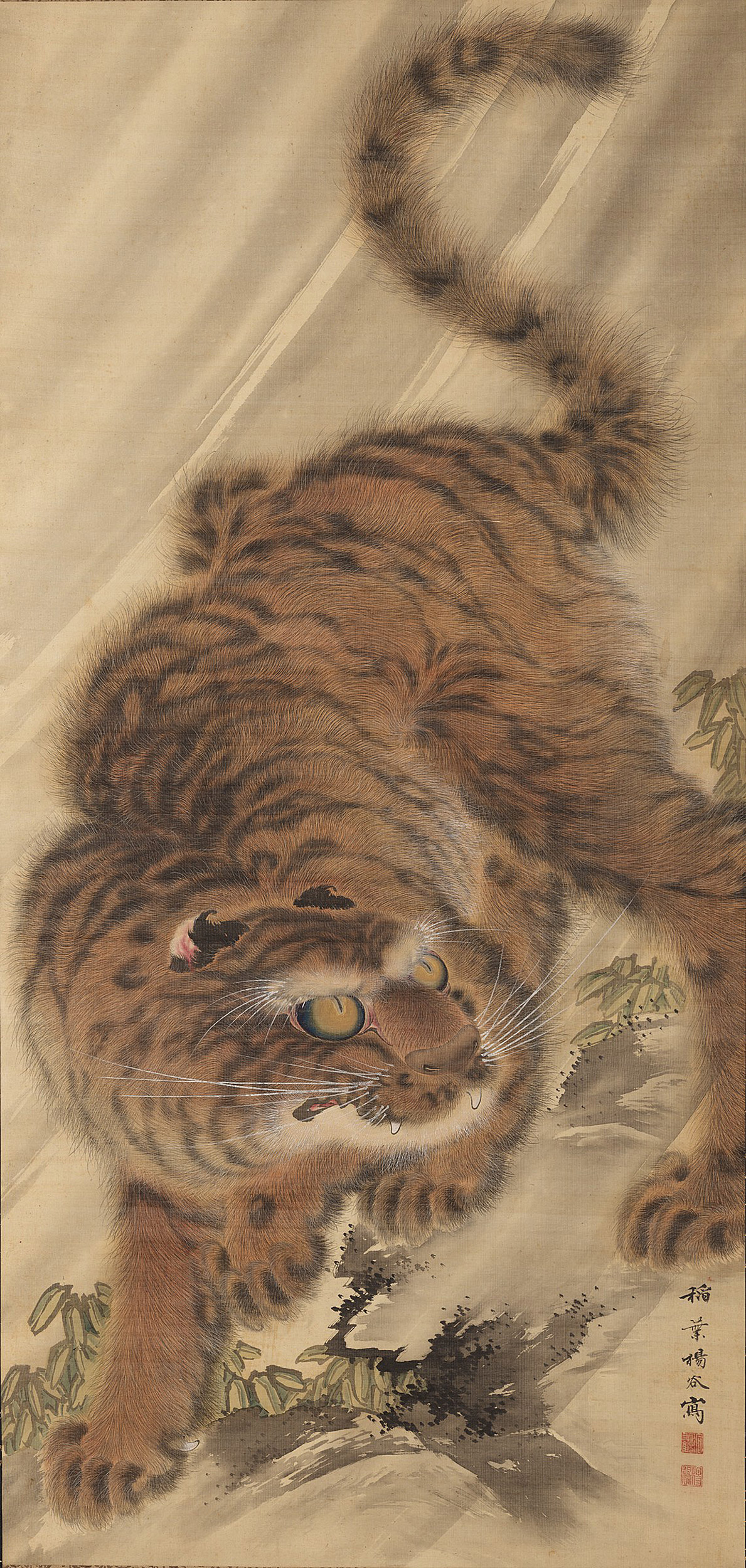

“Tiger in a Rainstorm,” Katayama Yōkoku, c. 1780–1801; “Harvesting Bamboo Shoots in Winter,” Tōensai Kanshi, c. mid-1760s.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

One example of that diversity is the art of the floating world, a school inspired by the period’s rapid urbanization as thousands of residents from the country moved to the shogunate capital, Edo, transforming what was a traditional fishing village in the 1600s to the most populous city in the world by 1800. In part a reaction to the shogunate’s orthodoxy and status-driven structure, in the floating world tradition, said Lippit, the people begin to see themselves.

“It’s the world of commoner painting in which the contemporaneity and buzz of the city, the fashions, the hairstyles, and the demimonde — the pleasure quarters and the kabuki theater, those areas supposedly off-limits for the warrior status group — are depicted,” said Lippit. “Here you see the floating world of the imagination in contrast to the fixed world of social obligation and feudal hierarchy.”

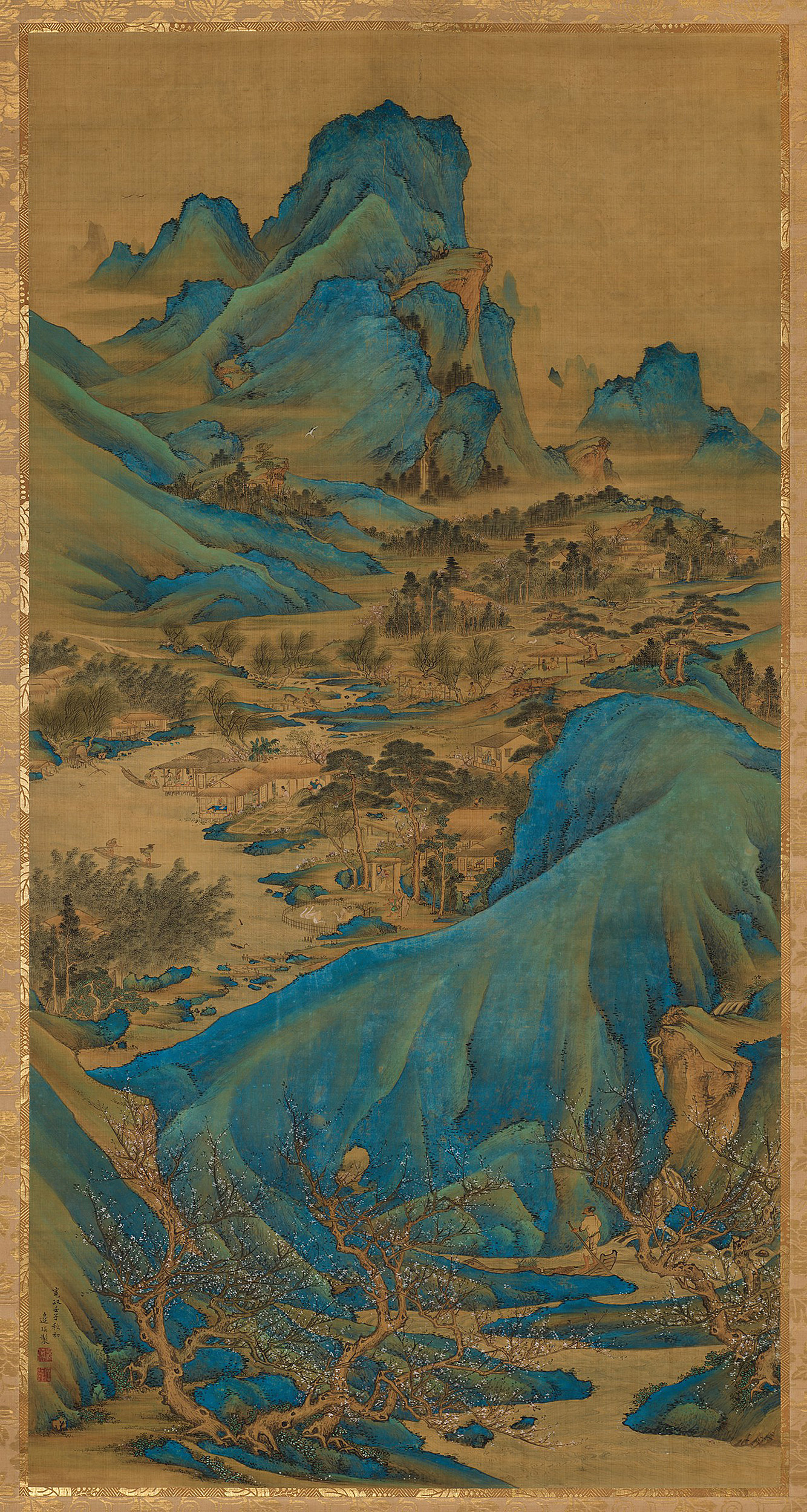

“Peach Blossom Spring,” Watanabe Gentai, 1792; “Mount Fuji,” Suzuki Kiitsu, c. 1835-43.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

A small hanging scroll, “Early Evening at a Yoshiwara Inn” by the artist Hishikawa Moronobu, “is a real gem of a painting,” and perfectly captures that essence, said Lippit. The painting depicts an intimate moment between a couple at an inn separated by folding screens from others nearby who are preparing a meal. “It’s meant to be generic; it’s meant to suggest a narrative without actually explicitly providing the story,” said Lippit. “In a work like this, the viewer is meant to project certain kinds of narratives of their own onto the scene.”

“Grasses and Moon,” Tani Bunchō, 1817.

© Robert Feinberg

Regardless of category, the show’s overall theme is beauty, one that often evokes a sense of something beyond words. Viewers are drawn to that ineffable quality with the large hanging scroll “Grasses and Moon” by Tani Bunchō, which opens the show and which curators liken to a giant window.

“It’s a very evocative way to start. We wanted that window, that essence there,” said Saunders of the horizontal work that honors the ancient Japanese tradition of viewing the harvest moon. “It’s what’s called a true-view painting — in Japanese, it’s shinkeizu. And the idea is not to represent an optical reality; it’s to represent the essence of something. And that is true of a lot of Japanese ink painting. You are not looking at an optical reality. It’s capturing something more.”

“Fish and Turtles,” Maruyama Ōkyo, c. 1772-81.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

Other works in the show are odes to both Japan’s natural beauty and the functional nature of many of the works from the period, such as the large folding screens that doubled as temporary walls or the hanging scrolls that could be unfurled to ornament a room for a specific event or season, then rolled back up and stored neatly in small, handmade wooden boxes. “Fish and Turtles” by Maruyama Ōkyo, a small, two-paneled screen, would have been placed on the floor for tea ceremonies and likely displayed in the summer months, said Saunders.

“You might bring out a painting for a particular season, a seasonal observance, or a particular guest was coming, or if you had a ritual going on. It’s about your taste; it’s about your guest’s taste; it’s about understanding your guests’ tastes; it’s about being in tune with the seasons,” she said.

What sets the small tea screen apart is how the artists incorporated two layers of silk, painting the aquatic life and one side and the water on the other, said Saunders. “When the light comes through this translucent stretched silk there’s a moiré effect, so it looks as if the fish are moving,” she said. “It’s a really special piece.”

Timed to coincide with the run-up to the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, when many eyes will be on the Japanese capital, the curators hope the show will connect visitors with a seminal moment in the nation’s art and history and inspire them to “ask questions and to think differently.”

“We are habituated to the ways we think and the ways we interact with the world,” said Saunders, “and when you encounter something like these Nanban screens, it reminds you to move your feet occasionally and to take another look and to practice some empathy for a very different way of looking.”

On March 19, the Harvard Art Museums will host a symposium, “The Feinberg Collection: Six Works,” in which scholars from Harvard and beyond will engage key works from the collection. The free event will take place in the museums’ Menschel Hall from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m.