As early as 1912, archaeologists were theorizing that climate change had contributed to the decline of the Maya, said Arizona State University Professor Billie L. Turner II.

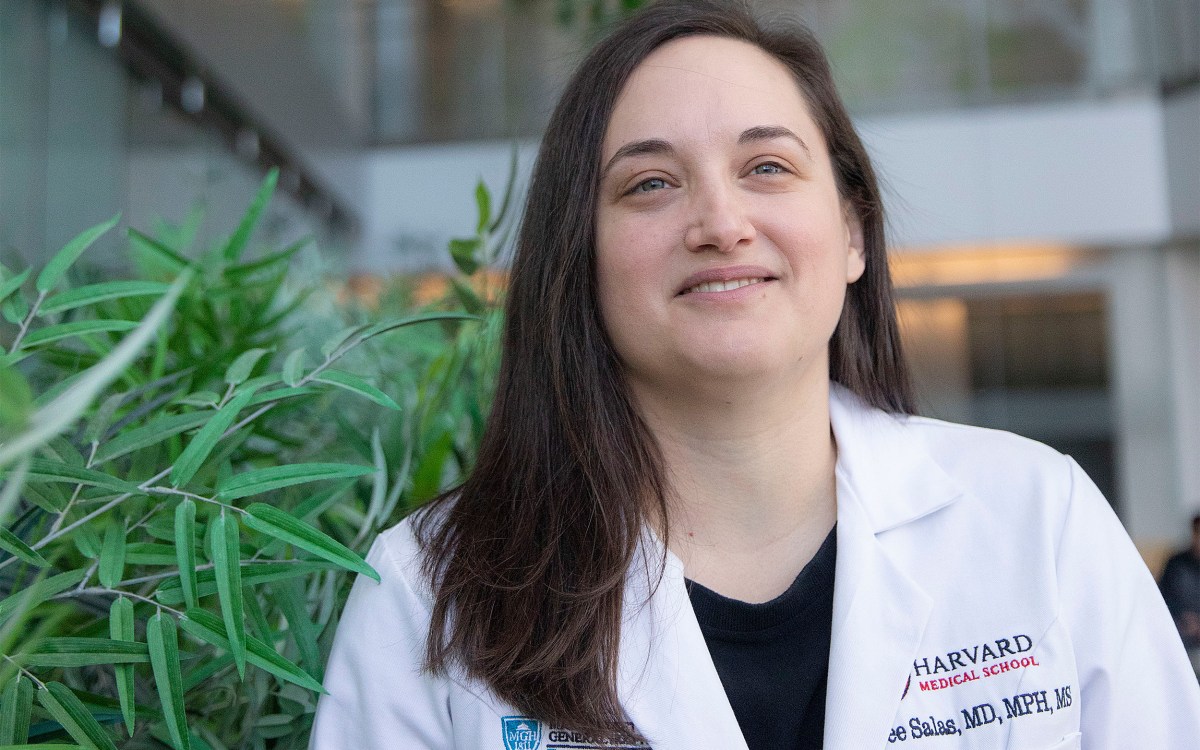

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

A great civilization brought low by climate change (and, no, it’s not us)

There are new clues about how and why the Maya culture collapsed

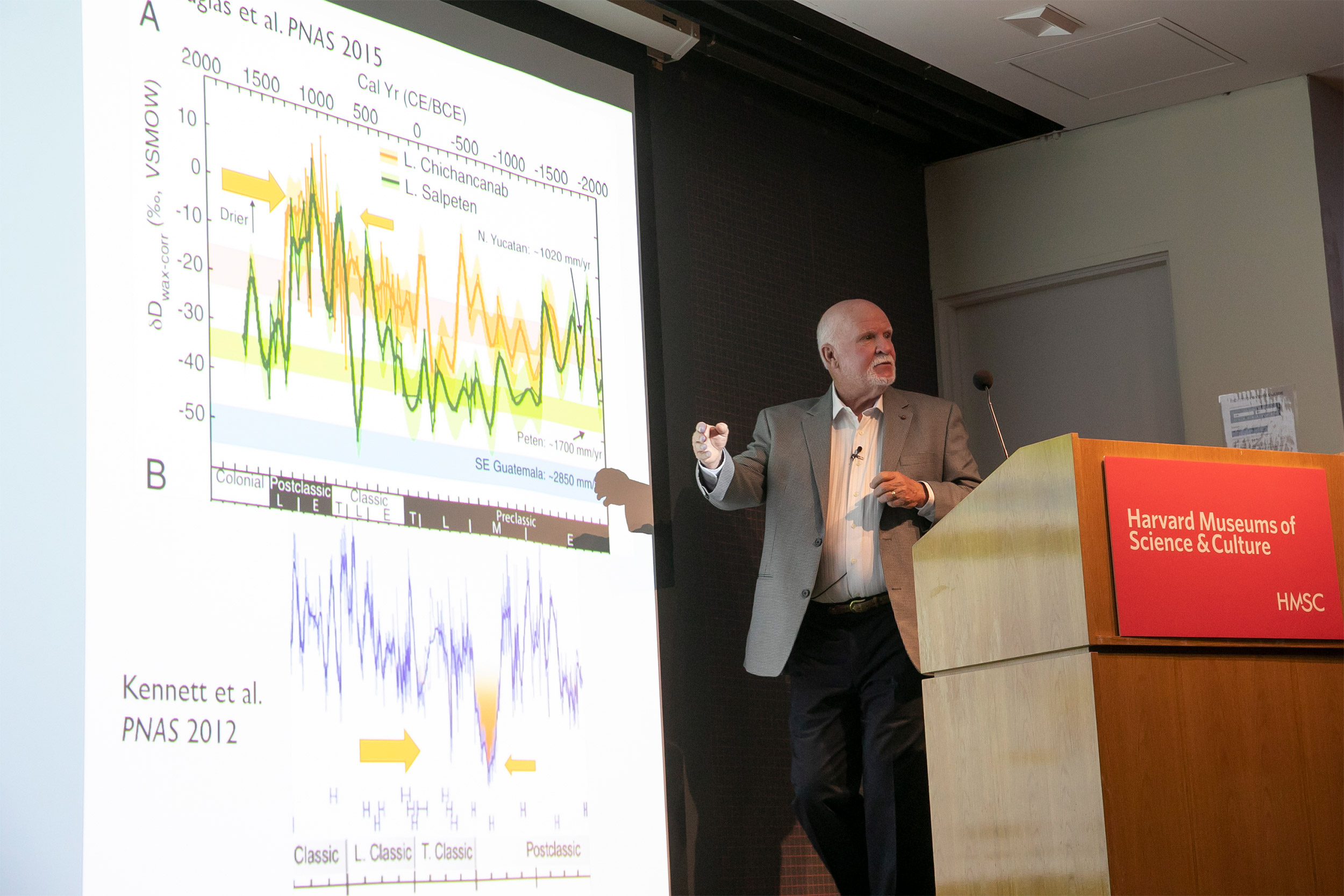

Climate change has been called the existential threat of our age. But it isn’t the first time a civilization has come into conflict with a shift in the natural world. Speaking on “The Ancient Maya Response to Climate Change: A Cautionary Tale” at the Peabody Museum on Thursday evening, Arizona State University Professor Billie L. Turner II discussed how climate change — likely made worse by unchecked development — brought low one of the great civilizations of our hemisphere over a thousand years ago.

Delivering the Gordon R. Willey lecture, Turner detailed evidence that two major droughts resulted in the decline and depopulation of a culture that not only had monumental architecture but also a sophisticated understanding of mathematics and astronomy. Elements of this theory have been around for a long time. As early as 1912, archaeologists were theorizing that climate change had contributed to the decline of the Maya, and by the 1970s, it was largely accepted that Maya lands had been densely populated and developed. However, recent evidence across disciplines goes a long way to explaining not only how but when the problems began — raising more questions along the way.

A human-environmental scientist, “working at the intersection of the social and the environmental,” Turner championed this interdisciplinary approach to understanding what may have happened between roughly 850 and 1000 A.D. to empty the elevated interior (or interior uplands) of the Yucatan peninsula, which had been, he said, the Mayan “heartland.”

Much can be found in the archaeological record. Following a long period of population growth, this area of dense farmland and cities “was virtually abandoned,” said Turner, the Regents Professor and the first Gilbert F. White Professor of Environment and Society, School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning and the School of Sustainability at Arizona State. Within a few hundred years, the forest had taken over once again.

The Maya had not only survived the five earlier droughts but had continued to build and to grow. So, why couldn’t they weather the last two?

Why this happened, however, is more complicated. The first theories, presented by Ellsworth Huntington in 1912, suggested that increasing precipitation had also increased disease. By the 1990s, evidence was pointing in the other direction — that lack of water had triggered the slide. However, said Turner, researchers still faced three major problems that made their conclusions somewhat speculative. The first was that much of the evidence of climate change, or even climate variability, was inferred by teleconnection — records of droughts in nearby regions, for example, which were not necessarily accurate for the Yucatan. Second, the evidence had not yet been pinned down enough in time, lacking what Turner called the specific temporal baselines of narrow five- or 10-year time periods. Finally, signs of precipitation on the actual peninsula — or the lack thereof — were not definitive or exact.

However, recent studies using new techniques have not only located evidentiary sources that come directly from the Maya heartland but that also can be definitively dated. For example, mineral deposits at the bottom of Lake Chichancanab show evidence of what Turner called “a megadrought,” prolonged periods of significantly less precipitation. Luminescence in stalagmites in the Macal Chasm provide additional chemical proof of years of “significant dessication” during the era from 750 to around 1150, while other sources, such as leaf wax lipids from around Lake Salpeten, offer more datable evidence showing not only that there was no water but when the shortage occurred.

“We now have fine-grain temporal data,” said Turner, “as well as relatively consistent signals. And because we have a large number of different proxies, and they’re all giving us similar data, we have consistent evidence that the drought was real.”

While there was some regional differentiation, said Turner, including the likelihood of more precipitation in the south, “all the data from all the sites charted show seven large drought periods” during the time studied, he said. Of most interest, he noted are the two “big dry interludes” that happened during the period — roughly 850 to 1000 A.D. — when the Maya civilization seems to have collapsed.

While the data resolved some issues there remained one nagging question: The Maya had not only survived the five earlier droughts but had continued to build and to grow. So, why couldn’t they weather the last two?

Evidence suggests that the Maya’s success may have made the difference, increasing their vulnerability and lowering their ability to deal with the fallout from harsher, drier conditions. Even before laser evidence revealed its extent, the Maya world was known to be very densely populated — possibly too much so.

“They had a huge population, a large urbanized population, and had made fundamental changes in the landscape,” said Turner. To support both farms and cities of 60,000 to 100,000, he explained, the Maya had cut down forests and increasingly manipulated wetlands, drawing water off into reservoirs and expanding agriculture into lowland wetlands. These moves consumed water that could not be spared during periods of drought. The Maya also unintentionally made their own agriculture less productive with their extensive deforestation. Removing trees, Turner explained, stopped the cycle by which the tree canopy would capture and return the naturally occurring nutrient phosphorus to the soil and also increased its temperature.

“The Maya had cut down so much of that vegetation and changed it in so many ways, they were amplifying the aridity that was already present,” said Turner.

At the same time, other factors — including changing trade routes and wars — came into play, issues that may have influenced or been instigated by a heartland already wrestling with environmental pressures. Calling it a “chicken or egg” scenario, Turner acknowledged that we may never have complete answers. At least not until a final question is answered: A thousand years after the fall of the great Maya culture, the interior uplands of the Yucatan remain scarcely populated.

“We have to understand why people didn’t go back,” he said. “Then we may begin to have better insights about the collapse.”

A video of the lecture will be viewable within three weeks at the HMSC Lecture Videos page, or directly on this Peabody site.