The good, bad, and scary of the Internet of Things

Radcliffe researcher explores ways regulation can minimize online risk, maximize safety, control environmental impact, and help society

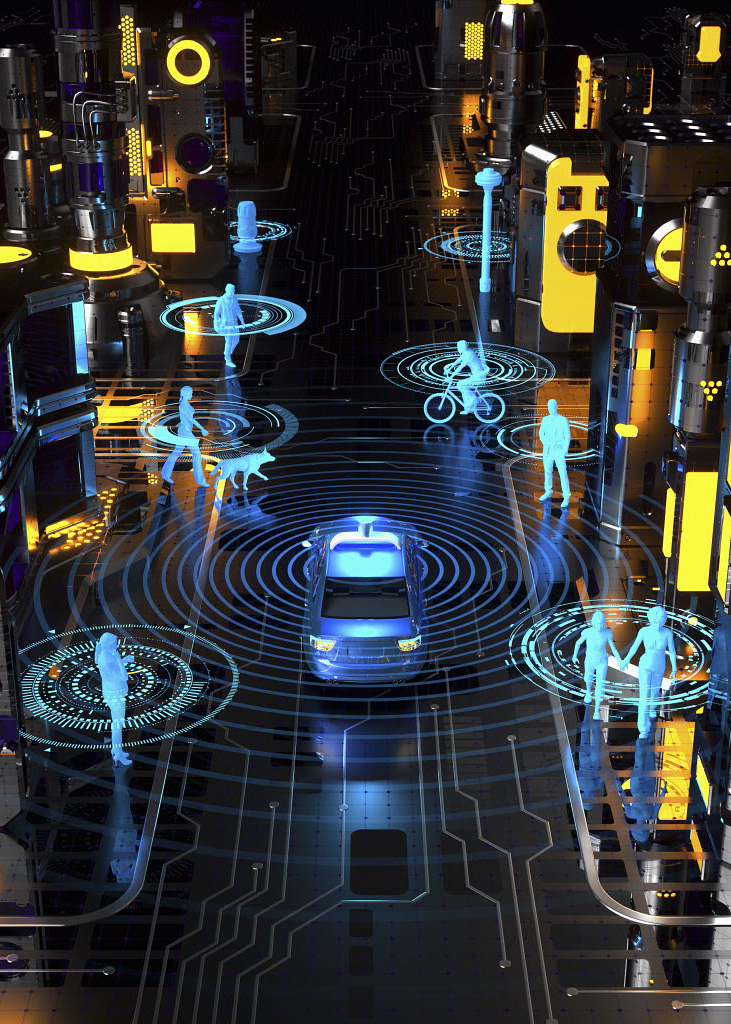

Illustration by Oliver Burston

This year, the number of web-connected devices around the world is estimated to hit about three for every person living: more than 20 billion gadgets, cars, smart speakers, and more. Already in use are some that help with tasks like driving, life-saving surgery, and reminding us to replace the milk in our fridge, said Fran Berman, a data scientist who studies how technology is increasingly part our daily routines and rewriting the way we live.

The Internet of Things, or IoT, as the expanding web-based network of sensors, cameras, smart systems, computing devices, machines, and appliances is known, will yield incredible benefits, while also introducing new problems around privacy, security, safety, and sustainability, said Berman, currently the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study’s Katherine Hampson Bessell Fellow. “It is going to change everything,” she said. “The question becomes: Is the Internet of Things a future utopia, or is it a future dystopia?”

It’s a question that keeps her up at night.

“How do we make sure that the IoT is good for us and good for the planet?” asked Berman, professor of computer science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y., during a recent conversation in her Radcliffe office. “How do we promote ethical behavior in autonomous systems? How do we promote privacy and protections? Because if we are not doing that, then the technology is not serving us. And at the end of the day, we want the technology to serve us; we don’t want to serve the technology.”

During her fellowship, Berman is developing a framework of “choice points” where policy, design, public awareness, and other interventions can promote an IoT that maximizes benefits, minimizes risks, and is good for the planet and society. With the help of three Harvard undergraduate research assistants, she is using the self-driving car as a case study to imagine what that framework might look like.

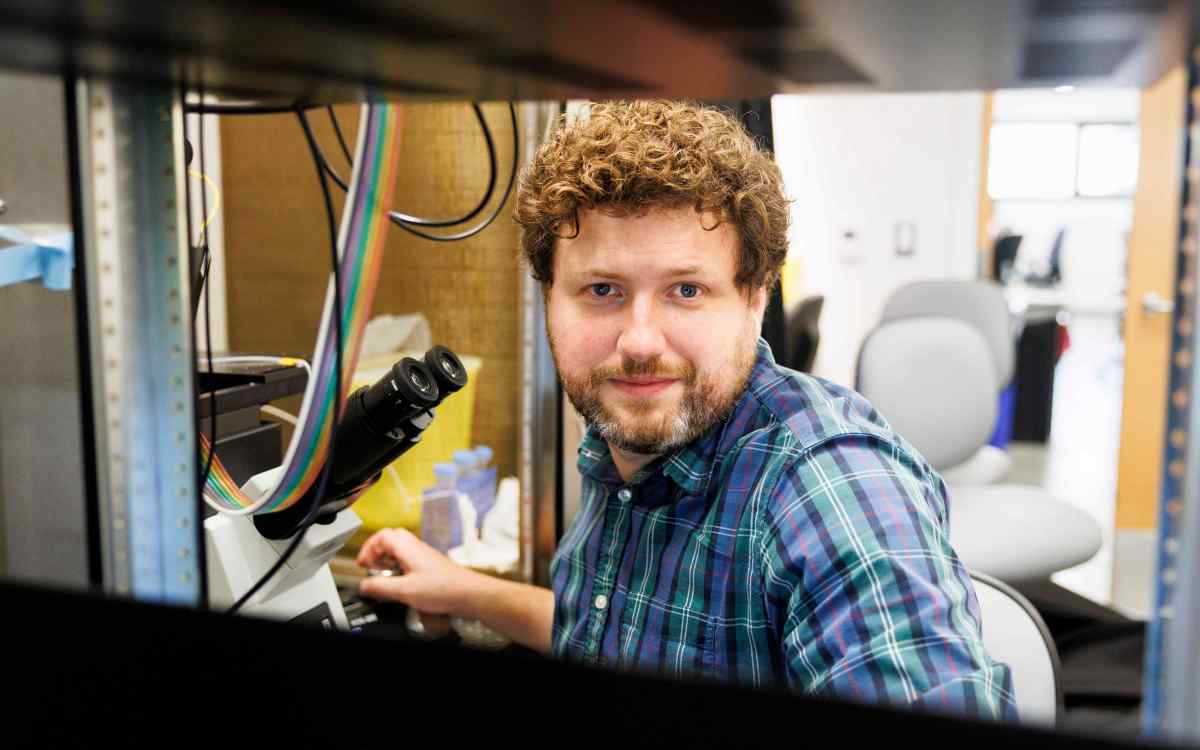

Fran Berman is studying the potential outcomes and consequences of an increasingly technologically automated world.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

During the fall semester Berman and her team did a deep dive into the social, environmental, legal, and other impacts of self-driving cars both now and in 30 years, when they are expected to be everywhere.

“This semester we plan to create a report and a graphic about the ‘impact universe’ of self-driving cars to demonstrate the extraordinary reach of IoT devices. Self-driving cars will not only change transportation but will also have impacts on land use, infrastructure, the workforce, policy and law, e-waste, use of rare materials, and a variety of other areas,” said Berman. She hopes the project will help promote a socially responsible IoT via recommendations for policymakers and raising public awareness, and to that end she is planning a book that expands on her Radcliffe work.

Developing such a complex framework, she knows, will require input from government, academia, business, and the general public, not to mention time, research, and hard data. Currently only California requires companies piloting autonomous cars on public roads to report the number of times the driver has to take over, known as disengagements. For many, ceding control of their steering wheel to a computer is a frightening concept, and there are reasons to worry. Hackers have exploited security vulnerabilities to take control of self-driving cars, and vehicles fully or partially operating with computer assistance have been involved in fatal accidents nationwide — though crashes represent only a small fraction of the overall trips logged.

Compiling the data to determine risk will go a long way to understanding those risks and securing public support, she says. So will protections that ensure that the data the car captures about its passengers remains private, said Berman, who notes that ensuring all the desired safeguards may require expansion of federal regulators like OSHA and creation of new agencies to promote public safety and security of IoT devices.

Berman’s project is tackling a range of thorny questions, including who is responsible for a crash when cars operate without a human driver; what it will mean for a police force that no longer needs to stop speeding motorists; how the layout of a city may change if demand for parking spaces plummets or disappears; and how manufacturers can make cars as green as possible, along with the impact of those design decisions. “The self-driving cars of 2050 are envisioned to be pods weighing hundreds of pounds instead of thousands of pounds,” she said. “Platoons of self-driving cars will have many fewer accidents, but when you’ve jettisoned the safety equipment to make the car more eco-friendly, individual accidents may be more severe. There are many trade-offs.”

“At the end of the day, we want the technology to serve us; we don’t want to serve the technology.”

Fran Berman

Berman has gained some real-world experience during her time in Cambridge by taking rides with her Harvard physicist friend Alyssa Goodman in Goodman’s Tesla, often in autopilot mode. The Tesla system requires drivers to touch the wheel frequently to prove they are awake (though videos have surfaced and gone viral that show drivers who appear asleep while cruising down roads, apparently on autopilot), and the car receives regular software updates that improve its performance. With more computer-operated cars that drive strictly according to the rules on the road in the coming years, driving safety, said Berman, will only improve.

Computer-science concentrator Emilia Cabrera ’21, one of Berman’s undergraduate research assistants, said being part of the project has helped her see the IoT in an entirely different light.

“I’ve obviously known about this technology, but I’ve never been considering it in the way I’ve been considering it this year,” said Cabrera, adding that the public-interest angle to Berman’s research will ground her future computer-science decisions.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Berman herself isn’t a total IoT convert just yet. Privacy concerns are keeping her from getting a virtual assistant or connected doorbell in her house any time soon. “I have to say that besides my computers and my iPhone, currently the smartest thing I have at home is myself. I don’t have a smart fridge, or Alexa, or any other smart-home devices because there are no consumer protections on privacy and often inadequate security. In the last few years, an Alexa shared information inappropriately and some smart refrigerators helped take down the internet.

“Until we create and enforce policy and legislation that makes these devices secure and private and transparent enough, I probably won’t buy them. But I’m hoping to help us get there.”