Torn and desecrated religious books and manuscripts found inside a 19th-century village mosque in Carralevë, Kosovo, in the fall of 1999.

Courtesy of András Riedlmayer

Harvard librarian puts this war crime on the map

András Riedlmayer catalogued years of cultural heritage destruction by Serbian nationalists in the Balkans, testified before the U.N.

In August 1992, in the Bosnian city of Sarajevo, nearly 2 million books went up in flames.

Fragile, 500-hundred-year-old pamphlets and vibrant Ottoman-era manuscripts disintegrated into ash as the building holding them, the National Library of Bosnia-Herzegovina, was shelled and burned. It was not the first act of cultural destruction by Serbian forces against other ethnic groups in the Balkans, and it certainly wasn’t the last: Over the next seven years, Serb nationalists led by dictator Slobodan Milosevic would wreak havoc across the Balkan region.

But burning the library and its contents was the act that drew András Riedlmayer into the Balkan conflict. And almost 30 years later Riedlmayer, a bibliographer at Harvard’s Fine Arts Library, knows more about the destruction of that region’s cultural heritage than almost anyone. He has testified against its perpetrators in nine different international trials and helped set a precedent of prosecuting this kind of destruction as a war crime.

“… if you really want to make a librarian mad, burn down a library.”

András Riedlmayer, bibliographer

“This is certainly not something I thought I’d be doing in my work as a librarian,” Riedlmayer said. “But if you really want to make a librarian mad, burn down a library.”

Riedlmayer has worked as the bibliographer in Islamic Art and Architecture at the Fine Arts Library since 1985. He has always been interested in the region of the former Ottoman Empire, which includes the Middle East as well as parts of Hungary, where Riedlmayer was born, and the Balkan Peninsula.

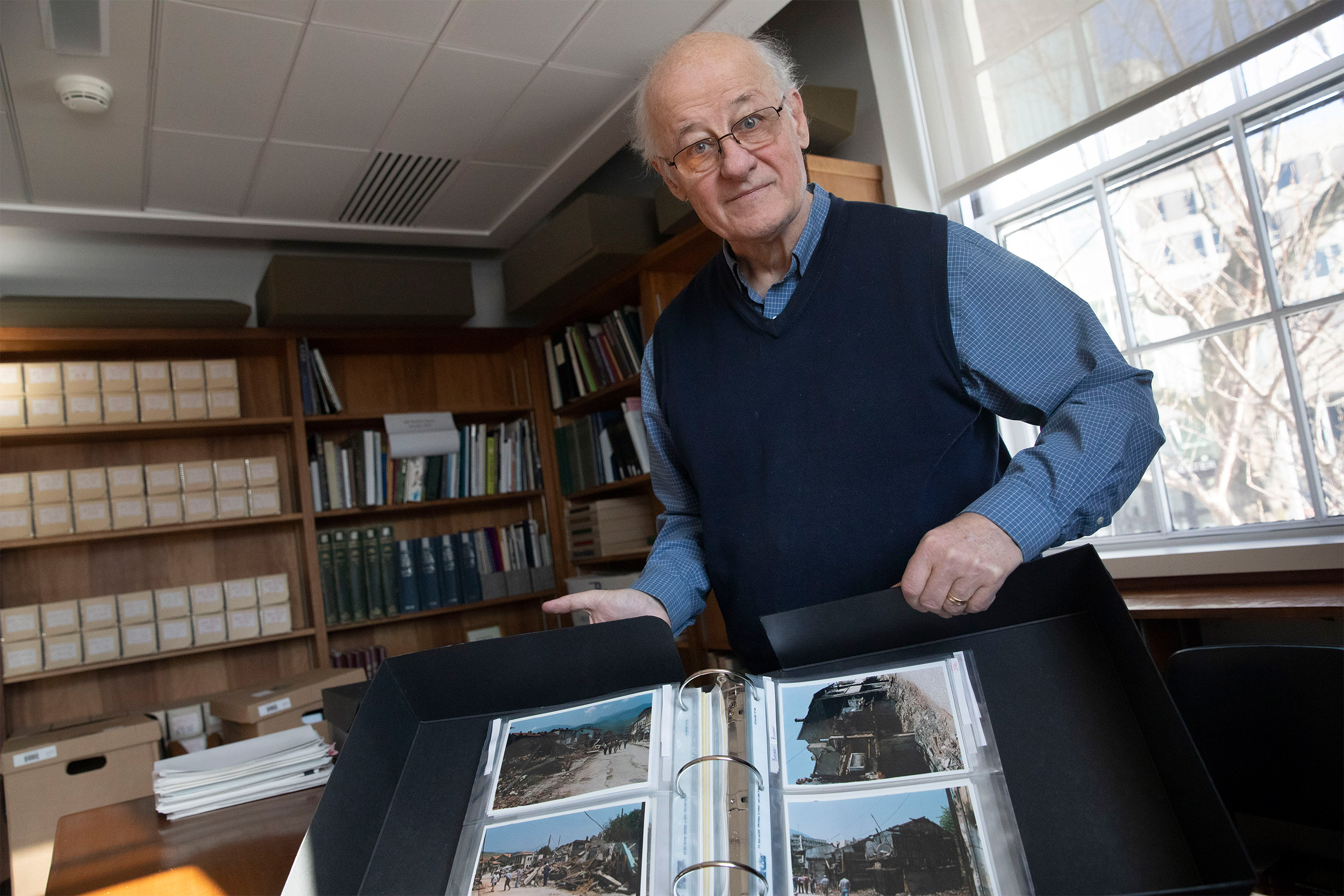

András Riedlmayer with photos from his many visits to the Balkan region in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

In 1992, when he read about the burning of the National Library, Riedlmayer knew it was an attack on more than physical objects. It was what he later testified to being “cultural heritage destruction”: intentional and unnecessary destruction of sites and records that act as a community’s collective memory.

The crime comes from a desire to not only kill individuals who are part of an ethnic or religious group, Riedlmayer explained, but to erase their existence, “remove any evidence that they were ever there to begin with, and give them no reason to come back.”

In the case of the Balkan region, cultural heritage destruction was part of attempted ethnic cleansing by the Serbian nationalist government led by Milosevic. The nationalists came to power amid destabilization in the former Yugoslavia and began targeting Bosnian Muslims, Kosovar Albanians, and other non-Serbs. They destroyed everything from ancient mosques to property records, all later presented as evidence by Riedlmayer when he gave expert testimony against Milosevic during the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY).

Agim, a Kosovar Albanian university student who worked with Riedlmayer as an interpreter, looks at torn religious texts (pictured) inside a Carralevë mosque that was burned by Serbian soldiers in 1999.

Courtesy of András Riedlmayer

Alex Whiting, a Harvard Law School professor and former prosecutor for the ICTY, credits Riedlmayer’s thorough documentation with lasting change in how cultural heritage destruction is viewed.

“In cases where thousands of people have been brutalized, driven from their homes, tortured, and murdered, trying to get the court to focus on destruction of churches or monuments can be hard,” Whiting said. “[Riedlmayer’s] work showed this was more than just destruction of buildings … cultural genocide is a people being attacked.”

Riedlmayer saw this firsthand during several visits to the Balkan region in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

After years of studying and writing about the conflict, and even collecting book donations to help rebuild libraries in the region, Riedlmayer finally went to the Balkans in 1999 on a grant to document architectural cultural destruction.

He found sheer chaos: villages without electricity or postal service; landmines buried in roadsides. Streets were crowded with people trying to get news by word of mouth, and walls were “absolutely plastered with funeral notices,” Riedlmayer recalled.

Despite the horrific circumstances, he said, the people he met were “amazing,” and they wanted their stories told.

That year, he visited more than 100 religious and cultural sites that had been deliberately destroyed during the conflict. He photographed and catalogued Catholic churches with collapsed steeples and mosques reduced to scattered stones covered with garbage. He collected the charred remains of books and, in one case, pages from a Quran desecrated by Serbian soldiers.

The National and University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina is ablaze following a bombing by Serb nationalist forces on Aug. 26, 1992.

Photo courtesy of the National and University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina

When Riedlmayer first found the ripped, dirty pages in a crumbling mosque, he thought to ask a village elder before taking them as evidence.

“These aren’t books anymore; we can’t use them,” Riedlmayer said the man told him. “Take them and show the world what was done.”

Riedlmayer left the region with an “enormous sense of responsibility” to the people he’d met. He had learned the United Nations wanted his findings as evidence of war crimes, and he felt this was his chance to give Balkan victims a voice on an international stage.

A year later, Riedlmayer came face-to-face with Milosevic, who was representing himself in the ICTY trial. Being cross-examined by the dictator was surreal, Riedlmayer said, but he was armed with a database of images and stories from the people Milosevic had victimized.

“I realized I knew more, and cared more, about this than he did,” Riedlmayer said.

Over the next 10 years, Riedlmayer was asked by the U.N court to compile additional expert reports on the destruction in the Balkans. He ultimately testified against 14 Serbian and Bosnian Serb officials accused of war crimes. Though Milosevic died of a heart attack before the ICTY delivered a verdict in his case, 11 of the others were convicted and sent to prison.

Beyond the guilty verdicts, Riedlmayer and Whiting saw the tribunal as a victory for understanding cultural destruction in wartime. Though it had been on the books since the Hague Convention of 1954, cultural heritage destruction as a war crime was prosecuted for the first time by the ICTY.

The 15th-century Bajrakli Mosque in the city of Peja, Kosovo, was burned by Serbian police in June 1999.

Courtesy of András Riedlmayer

The tribunal “put this crime on the map,” Whiting said. “It’s now part of the discussion; it shapes how people understand war and what’s permitted in war.”

He noted that last week, when President Trump threatened to destroy cultural sites in Iran, he was met with immediate backlash and had to walk back his statements.

“That means something right there,” Whiting said.

Riedlmayer said he hopes the precedent set by the ICTY will prevent at least some future destruction of cultural sites.

But he is not done with his work to show the world what transpired in the Balkans in the 1990s. He continues to speak and write about his findings. The documents and photographs he collected in the Balkans are now also accessible to researchers as part of the Fine Arts Library’s special collections.

Preserving and publicizing records of the destruction is Riedlmayer’s ongoing pursuit of justice and closure for those who lost so much in the conflict. He still feels the weight of responsibility to the victims he met in 1999, he explained. “Their stories are still being told.”