Sadada Jackson, a member of the Nipmuc tribe and a recent graduate of the Divinity School, curated an exhibit of indigenous-language materials at Tozzer Library.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Curating the future

Exhibit highlights indigenous historical materials at Tozzer

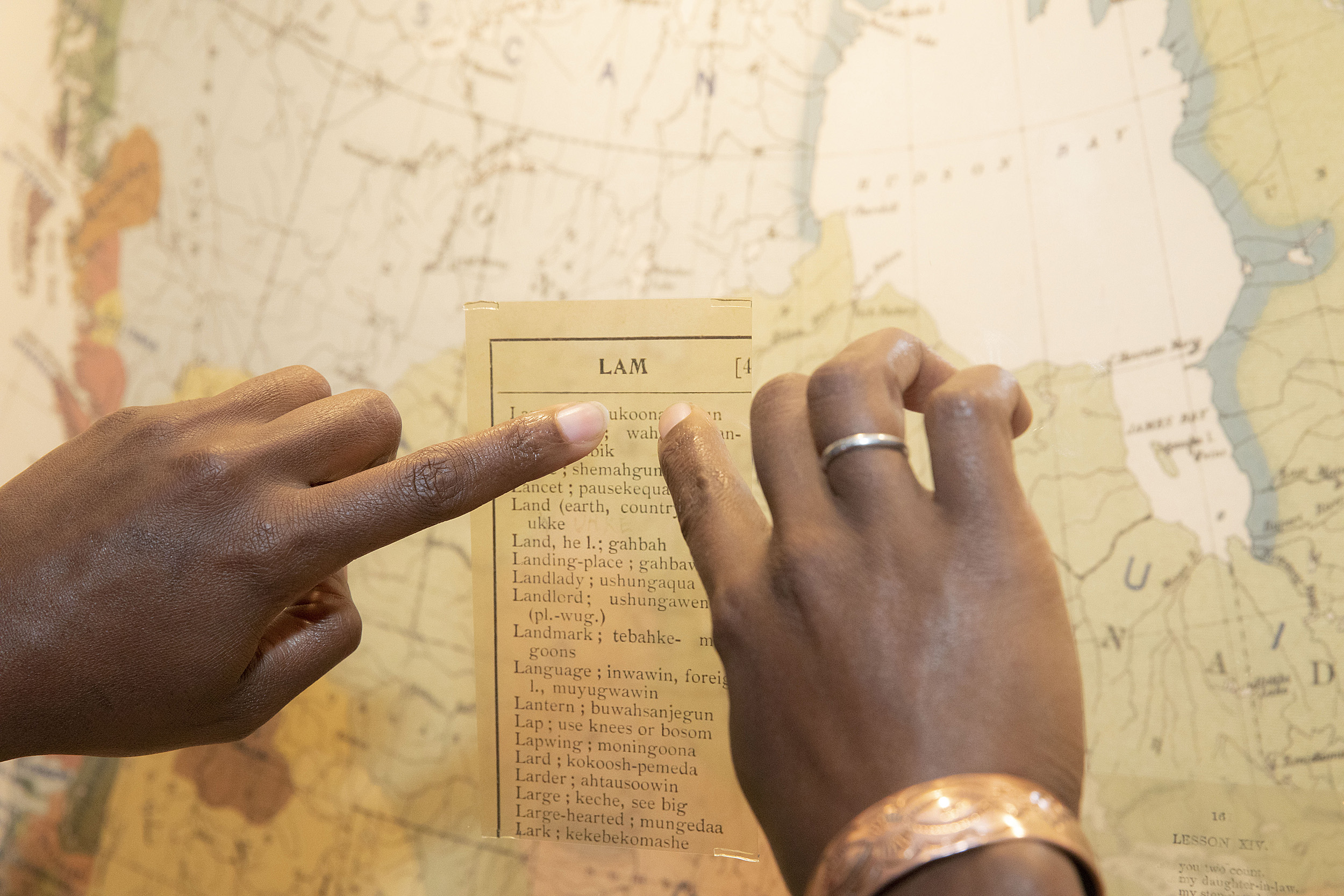

While sorting indigenous-language materials as a graduate research assistant at Tozzer Library, Sadada Jackson came across a 1903 English-Ojibway dictionary printed by Canadian missionaries, an 1832 spelling book in the Seneca language with English definitions, and an 1857 journal handwritten in Cherokee.

Jackson, who earned a master’s of theological studies at the Harvard Divinity School this past May, was so struck by her findings that when officials at the library, which houses anthropology and archaeology collections, asked her to do a public exhibit based on her work, she accepted with enthusiasm.

“It was an opportunity to give back and leave an offering for inspiration; a way to honor the past and take heed of the future,” said Jackson, who dedicated the exhibit to the speakers of indigenous languages and to “all who are listening.”

Curated by Jackson, “Our Land Our Language: Reflecting on North American Indigenous Language Materials” will be on display at the front entrance of Tozzer until June. It includes two maps of the U.S. and Canada with the precise areas where indigenous languages were spoken in 1903 and 1915 highlighted and overlay indigenous-language texts. The maps were created by J.W. Powell, who was head of the Bureau of Ethnology from 1879 until 1902.

For Jackson, an African American and a member of the Natick Nipmuc tribe, the exhibit gave her the chance to curate a display intended to help visitors deepen their understanding of native cultures. She also aimed to give people of indigenous descent a place to find a piece of their history.

“I wanted to create a space for people who are indigenous, whether they speak or not their indigenous languages, where not only they can be themselves, but also inquire about themselves,” said Jackson. “It’s important for all marginalized people, especially black and native people, who often were not seen or were gazed upon, to have a space where they can see themselves reflected.”

Sadada Jackson shows a map with English translations for Ojibway words and phrases.

Jackson, who spent a year surveying part of the indigenous language materials at Tozzer, helped organize part of its North American collection, which now features 122 items in 24 languages, including Apache, Inuktitut, Mohawk, and Zuni. Among them are dictionaries, manuals of grammar and vocabulary, spelling books, catechisms, hymns, and gospels translated into different native languages. They can be viewed online at Zotero Library.

But the work is not finished. Tozzer, which has one of the world’s largest anthropology collections, with an emphasis on the indigenous peoples of the Americas, continues to grow its North American collection. It is also in the process of surveying indigenous materials of South America and Mesoamerica.

Making materials available to the broader community remains a goal for library officials. Susan Gilman, the Tozzer’s librarian, recalled the powerful impression left by the visit of a Navajo elder who examined some texts housed at the library. When he read the texts aloud, everybody in the room was shaken, she said, as the words came to life.

“We often get requests from people working on books and dissertations, but less so from the general public, and we’re open to the public,” said Gilman. “It is wonderful to make these materials more visible to not just scholars but community members.”

Having a wider range of individuals engage with library materials will likely yield insights that may shed fresh light on research and scholarship, said Gilman, and is a strong reminder of how personal stories from the past can touch people in the present.

Such was the case with Jackson, whose grandmother, Mildred Selden, was also a black Nipmuc. The exhibit is interwoven with Jackson’s personal narrative and includes a video of her reading a letter to her grandmother. In it she recalled that the older woman, who was paralyzed from the neck down for the last 13 years of her life due to an injury, taught her how to listen and think about language beyond words — a skill she employed while planning the display.

“The exhibit is the beginning of a conversation, and at the base of that is honest listening,” Jackson said. “I hope it inspires people to see beyond the video and the maps and start to make changes they need to make so that this kind of history doesn’t repeat itself, so that we don’t ever have to have languages that are lost.”